Project Report: A Comedy-Based Psychosocial Intervention for Teenagers Experiencing Adversity

Teen #1 (to me): Why are you doing this program? And why us?

Teen #2 (also to me): And do you know Ariana Grande?

These were my first interactions with some of the youth that I had the pleasure of working with at SOS Children’s Villages in Cape Town, South Africa. Although I unfortunately do not know Ariana Grande, I definitely do know why I spent 6 weeks at an NGO that houses orphaned, abandoned, and precariously housed children for my Leadership-in-Action (LiA) project through the Laidlaw Foundation.

I knew I wanted to work with children experiencing adversity due to the research that I did last summer through Laidlaw. In looking for a partnership, I was impressed by the work that SOS Children’s Villages had been doing in so many countries (over 130!). After having a wonderful meeting with Sipelile Kaseke—the National Programs Director of all SOS South Africa locations—I was placed in the SOS Cape Town location; I had successfully pitched my proposal of a comedy-based psychosocial intervention for teenagers experiencing adversity. This would involve comedic improvisation—a performance art form that involves acting out scenes in front of one another without any prepared dialogue/scripts. I then had the opportunity to connect with Zama Mbele and Alois Aloo, who are both exceptional SOS Cape Town staff, and who I miss dearly as I write this.

Through my various meetings prior to my arrival last May, I became aware of the basic setup of the SOS Cape Town location: there were about a dozen homes within a gated entrance, and all of them housed youth—all of whom had nowhere else to go. Within these homes of roughly 6–8 children, there was one child and youth care worker who lived there as their “mom”, 24/7. Needless to say, this was quite a unique living arrangement, and it made me eager to craft a comedic improvisation curriculum that met this community’s needs.

SMART Goals

To do this, I met on a monthly basis from January 2024 up until my departure in May 2024 with my primary staff contact and youth coordinator at SOS Cape Town—Alois Aloo. Throughout our meetings, I was advised that the following psychosocial outcomes were of priority for this centre’s teens:

- Self-regulation

- Resilience

- Collaboration

- Kindness

- Generosity

After achieving my first SMART goal (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Timely) of my LiA—completing a thorough pre-departure needs-assessment with the youth coordinator—I moved onto my second SMART goal: developing a curriculum to fulfill said needs. I knew I had a lot of work ahead of me, so I immediately started crafting a curriculum specifically designed for the teens at SOS Cape Town. I had been performing and instructing comedic improvisation for youth for over 10 years, so I had many exercises in my mind to choose from. However, I had never been this intentional with the design of my classes; I would usually just make an educated guess as to what comedy exercises students would enjoy based off the energy of the first class. I was now being more methodological about it; for instance, I made sure that a certain number of games curtailing to self-regulation—one of the previously discussed psychosocial outcomes—would be present. For example, one of these games was Emotional Quadrants, where the space is split into four emotional quadrants: one is angry, one is happy, one is sad, one is scared. Whenever children would perform their improv scenes, they would do it in the emotion that was associated with the quadrant that they were currently standing in (i.e., maybe their scene starts in the “angry” quadrant, but then they move to the “sad” quadrant where they have to continue the same scene but with the new emotion). You can see how this consistent flexing of an emotional muscle (e.g., going from angry, to happy, to sad, back to angry, then to scared), could help promote self-regulation—the targeted psychosocial outcome mentioned earlier. This is just one of many examples as to how I developed my curriculum to fulfill the psychosocial outcomes discussed with the centre’s staff.

.jpg)

Finally, my third SMART goal was quite different: I had to do something very enjoyable for myself every single weekend that I was in Cape Town. I emphasized had because this is, unfortunately, an extremely foreign concept for me. I am proud of what I have achieved so far in my academic journey, but in retrospect, it did come at quite a cost (e.g., limited social life), which I now feel could have been approached differently. However, what motivated me to fulfill this goal, was the sad amount of burnout that I witness in childcare fields here in Canada. I have had the pleasure of working in childcare for about 10 years and, generally speaking, the more demanding the job might be (e.g., working with a population experiencing trauma), the less supports in place for the staff who are courageously doing that type of work. For the sake of the children at SOS Cape Town, I refused to become another childcare burnout, so I really emphasized the need to do fun activities on the weekend.

I was about to run this comedy-based intervention for teenagers three times a week, while training their staff on delivery of said curriculum for when I am gone, while doing a soccer-based psychoeducational program for girls, while also doing a comedy-based psychosocial intervention for preschoolers—if I did not take care of myself, all of these programs would have only (barely) lasted one week. Of note, as much as I would love to discuss all of these programs in this report, due to concerns with length, I will be focusing on the comedy one for teenagers. In short, although the first few times of engaging in self-care were guilt-laden experiences (e.g., going to the top of Table Mountain National Park during my first weekend and having the lingering though, “Shouldn’t you be revising your curriculum at home?”), I eventually got used to it and it became second-nature. I started thinking instead, “that was an extremely taxing and rewarding week, of course I need to go out and do something fun to refuel myself”—which is quite remarkable if you know me at all.

Challenges

My main challenge involved creating a meaningful and sustainable impact in the community at SOS Cape Town. Even on my flight there, I recall bonding with a passenger sitting beside me (who is now a great friend!) about my concerns of showing up as this White-looking Western guy pushing a performance arts intervention that may or may not be accepted by these teenagers. Up until the first day, I really thought it could go either way. The staff contact, Alois, had reassured me that they would love this, and he even checked with them before my arrival; however, I was still worried that, once they experienced comedic improvisation, that they would outright reject it—boy, was I wrong!

.jpg)

During our initial comedy session, we did some basic games to get them used to trusting their instincts and thinking-on-the-spot, which are essential for improv. The amount of joy that I saw in one of our first exercises, which simply involved them saying “whoosh!” to one another in a circle, one at a time, was incredible. The purpose of the game was to simply copy whatever type of “whoosh” that the person beside them did and that nobody should purposely try to alter the “whoosh”—it always naturally transforms in its intonation/emotionality. Even in between sessions afterwards, some teens would randomly go up to me if they saw me walking in the centre and we would start “whooshing” each other and doing the exercise. This was after one day—so I was confident I was mostly “in”, but I could still see some hesitation with certain teens. That is why, to assist in resolving this challenge, I ended up semi-unexpectedly (but tactfully) opening up to the group during the first week about my own experiences with childhood adversity and how comedy helped me overcome it. That same evening, I witnessed something quite incredible. I often took an Uber from the centre to my Airbnb at the end of the day, and once I opened up, about half of the class opted to stay and make sure that I got home safe. They did this by, endearingly, taking note of the Uber’s license plate “in case you get kidnapped” and interrogating, in a charming way, my Uber driver, who graciously went along with it. That is the moment where I knew I was “in”. I learned that vulnerability, done tactfully, with this population in particular, was a catalyst for increased quality within facilitator-teenager bonds within these types of interventions. Finally, the challenge that I had discussed with my new friend in the airplane on my way to Cape Town was no longer a concern, and my biggest fear (seriously—I was losing sleep over this leading up to this trip) was alleviated.

Leadership Skills

As you can imagine, coming to a foreign country and proposing a psychosocial intervention with an activity (improv) that they’ve never even heard about before could demand the use of leadership skills. Specifically, my leading of these comedy psychosocial sessions demanded that I step up my communication. Quite early, I noticed that certain individuals were getting upset at others who were struggling with certain exercises. I saw this as a projection onto others of the potential harsh experiences they may have gone through in the past when they struggled to learn an endeavor. However, this demanded from me, as the facilitator, to almost “deprogram” their mentality of “getting everything right, all the time, right away, or else there would be harsh punishments”. I recall multiple psychoeducational breaks that we took, as a class, where we discussed concepts such as growth mindset and the importance of accepting failure and struggle while learning comedic improvisation—which (I reminded them) is NOT an easy art form to learn! By owning the space in terms of setting collective expectations, I was able to reassure those who were getting anxious about those who were struggling within certain exercises.

I am also grateful to have worked on my cultural humility leadership skills while I was working in South Africa. This especially came about when I noticed that certain improv scenes would sometimes lead to a teen making a homophobic comment, which I would always say “new choice” to, which was a rule that we established on day one where I could override any choice in a scene if I felt it made anyone feel unsafe. However, conversations with certain teens after class gave me the impression that there might have been a larger systemic anti-LGBTQ view among the children at the centre. The way to discuss this where I am from, Canada, is quite different then how to address it where half my family is from, Morocco, which is also different than how to address it where my LiA was, in South Africa. I kept the cultural context in mind to show my eagerness to learn the root of such views within the teens at the centre. I quickly understood that it had to do with a (false) association with LGBTQ equating to sinfulness within Christianity. Of course, I did not shame them because 1) it is inappropriate to do so for vulnerable children especially and 2) social psychology shows that that will most likely strengthen their prejudice if anything. However, I did reach out for help with another scholar from another foundation that I met on an open-top bus tour in Cape Town. She had a lot of experience running youth groups in South Africa, so I thought she might be able to give me guidance. She said that research shows that one of the best ways to address this is by sharing a personal story about a personal connection you have within the LGBTQ community and how you care about that individual. I took her advice and did this one day after class and, right away, the teen’s views changed from rigidity to openness. It was stunning to witness—it was almost as if they were yearning for an adult to create space to have a conversation about this. This helped remind me the importance of approaching culturally sensitive topics with empathy, active listening, and self-awareness especially.

Ethical Considerations

I especially learned the importance of integrity within ethical leadership during my final week of my LiA project. When my staff contact at the NGO drove me home on the eve of our show day, he sadly shared the news regarding the venue for the final comedy class show—it was no longer available. Naturally, I was devastated to hear this, but I immediately knew that there was no way that I was going to look these teens in the eye and tell them that our class show was cancelled. I would be lying if I did not have the passing thought of entertaining the idea of simply accepting that there would be no show. Frankly, it was literally my last day of a very demanding, very draining (but very rewarding!) 6-week leadership project; I had dealt with a fair share of curveballs already, and there was a part of me that just wanted to cave and tell everyone that the show was cancelled. The day of the show coincided with my final day at the centre, so it was impossible to reschedule it to another day. However, I recall from my initial pre-departure meetings with the SOS Cape Town staff how they stressed that these children have been consistently let down by adults in their lives. They emphasized the importance of understanding this and how vulnerable they were in this regard. Sure, the “easier” option for me could have been to concede and say the (classic) line “due to unforeseen circumstances, etc.”, but I refused to be another adult that lets them down.

Therefore, I relied on my talents that I had cultivated in the past 6 weeks to generate a feasible plan to maintain my integrity. I went to bed not exactly knowing what would happen, but I had a surprising amount of confidence and calmness—in my heart, I knew I was going to come up with something. The following morning, I woke up with an idea that saved our show. Originally, we had dismissed the idea of performing outdoors at the centre due to the early sunsets and the children being occupied beforehand; however, I found a way to work around this. I secured two of the NGO's vehicles and brought them to adjacent sides of the centre's basketball court (i.e., our makeshift "stage"). I then had these vehicles turn their front lights on throughout the show. The end result was more beautiful than I could have imagined; the light from the two vehicles truly made it seem like we were at a real theatre with real lighting. The teens were ecstatic, and the show was saved. I made sure to keep my composure with the teens and not stress them out with these logistical issues prior to their performance. This definitely paid off because, under the bright shining lights of the NGO's vehicles, they put on an incredibly hilarious show for the entire centre. The irony of having to "improvise" a way to make a comedic improvisation show happen is not lost on me, and it makes this memory that much more special. It was a solid reminder that ethical considerations, such as coming up with a new plan to stay accountable and maintain integrity with vulnerable youth, is not always comfortable (far from it, actually), but with patience, it is ultimately rewarding.

Collaboration

I also learned the importance of building collaboration through problem-solving skills—especially as we approached the date of our final comedy show. The entire class was super excited about our class show, which involved an improv show for the entire centre on my last day there. For 6 weeks, we had went from beginner exercises involving doing scenes one word at a time (e.g., Person 1: Once, Person 2: ..upon, Person 3: …a, etc.) to engaging in complex multi-person scenes involving multiple characters that were cognitively demanding. However, a few rehearsals before our show, one of the leaders of the group had suddenly quit out of frustration with which games were voted in for the final show. I had to make sure that 1) not everyone was going to suddenly quit, and 2) ensure that the class’ anxiety level did not reach an unsustainable level. To do this, I shared anecdotes of similar circumstances that happened to me when I have done shows in the past (it’s surprisingly common how often someone might quit a show a week before opening!) and I reminded them of our collective strength and how we could overcome this. I also emphasized that I would not tolerate any negative behaviour towards the individual that quit and that, if she decided to, we would welcome her enthusiastically if she came back. We all then started doing “check-ins” at the beginning of our final weeks of rehearsals where everyone, one at a time in front of the class, would share in about a minute or so how they were feeling that day and if there was anything we could do to support them. This set the tone for the rest of the classes and, to everyone’s delight, and after many one-on-one conversations that I had with her, the teen that quit then decided to rejoin the group again for the final show. Not only that, she ended up being the one to give me a (surprise) gift in front of the centre after our show, along with singing a song to me in front of everyone. This ability to foster collaboration with other team members (i.e., my amazing teen performers) by using problem-solving skills reminded me of the importance of staying curious when noticing someone’s behaviour—you never know what might be going on behind-the-scenes.

.jpg)

Conclusion

Comedy Magic

I am proud to share that, upon meeting with the centre’s director (Zama) before my departure, I was advised that, not only were all psychosocial outcomes achieved (i.e., self-regulation, resilience, collaboration, kindness, and generosity), including being told that students who had refused to go to school were going “ever since your classes”, but that everyone at the centre wanted me to extend my stay. It broke my heart to tell her, other staff who I became close with, and the many children under my care, that I could not extend my stay. Nonetheless, even though I had to sadly leave at the end of my project, I will forever have the memory of our final class show in my mind: seemingly out of nowhere, the shyest individuals let loose and quite literally stole the show—I was in absolute awe. I will always remember our final class huddle, 5 minutes before the show, with the audience all ready and waiting. We all got physically close and I could sense the nerves that everyone had. I made them all look me in the eye and I told them that:

Everything that happened to you before this moment, all that stuff that wasn’t fair, that wasn’t in your control, all that stuff you didn’t ask for, or the stuff you did ask for and didn’t get, when you get up on that stage...it doesn’t matter: you show them that IN SPITE of all of that, here I am laughing and performing and making others laugh; do not let them win.

We all shared a good quick cry together, and they went out and blew everyone away. This was not to be the only time that my jaw dropped to the floor; I recall a breakthrough moment near the half-way point where the teens did an improv scene about characters who were making fun of their actual place of residence, SOS Cape Town (e.g., Character #1: “Ewww look at these poor children at this poor place, what a pity!”). However, and quite remarkably, the teens in the scene did a very advanced satirical twist on it because, as the scene progressed, they slowly revealed negative attributes of those characters that they created (e.g., “I’m going to donate to SOS to say I did something, anyways, I love being selfish and empty inside”), which brought about a type of laughter that I had never heard in my 10 years of doing this. Its intonation was so deep, it felt cathartic for these teens to witness one of their deepest anxieties come to life, and then they defeated it by collectively laughing the stigma away. Throughout moments like these in my program, I made sure to give space for psychoeducational components where we discussed how exercises made us feel. It was beautiful to witness the connections made during these moments among the teens (e.g.,”..hey! I felt like that, too!”).

Media Exposure

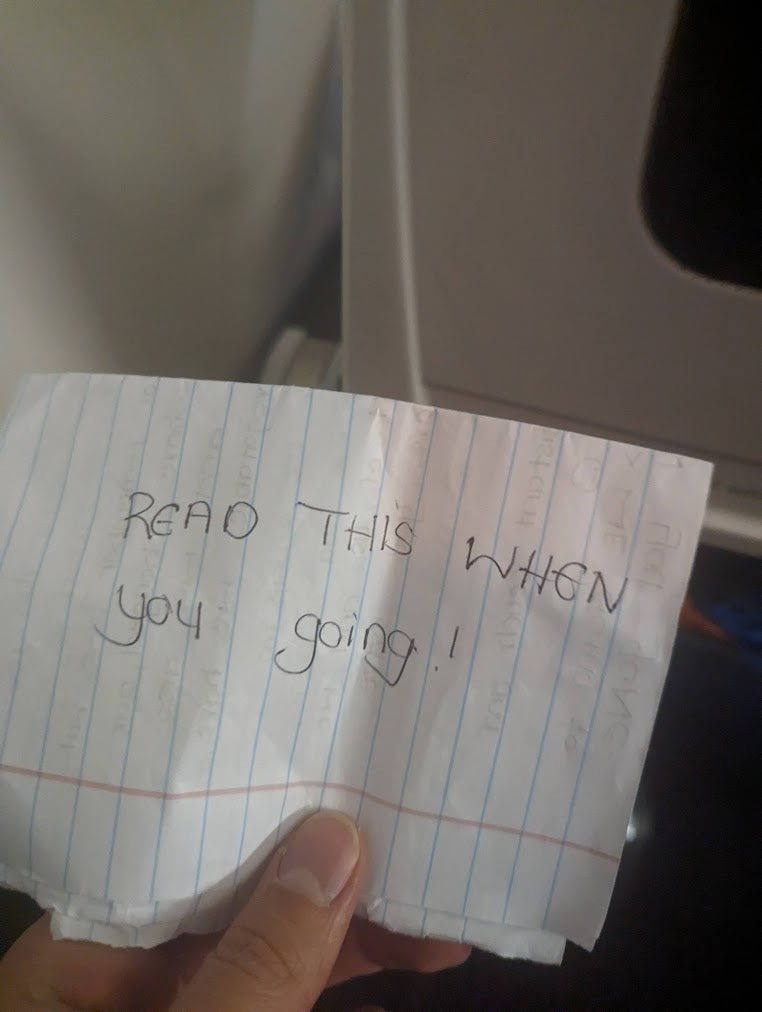

In the end, my work was picked up by a local radio station, Heart FM, and I had the privilege of sharing to thousands of listeners the benefits of comedy-based psychosocial interventions for children experiencing adversity, and how any type of volunteer should be racing to apply to work with this wonderful group. The following day, SOS Cape Town received multiple volunteer inquiries who all referred back to my radio interview. One of these individuals, who works out of a university nearby, even offered to continue co-facilitating my classes in my absence. This helped alleviate some of my concerns of engaging in a sustainable way because momentum was picking up for my work to continue after I left—I wanted to avoid the cliché voluntourism trap, so I made sure to engage in meaningful tasks, such as training multiple staff members how to deliver my comedy-based curriculum after I leave. I even donated my entire curriculum and am offering support during my physical absence. In fact, just the other week, they livestreamed to me a comedy performance that the teens did to a public audience (this would have never been possible on week 1, I am so proud of them!), and it was beautiful to witness. Overall, it has been difficult, but in a good way, revisiting my time there to write this report, because I desperately miss everyone there. On my final day, I was given a letter by the teens, but I was told to only open it while I was on my plane back to Canada. When I did, I started tearing up after reading this part, “And I want you to remember we will never forget you, you have changed our lives in a good way and we also won’t forget the vegetables we have ate with you.” (I often brought fruits and vegetables to class!)

Final Thoughts

In short, this 6-week LiA project has turned into a lifetime commitment. It has solidified what I want to do academically (I will be applying to clinical psychology PhD programs this year in hopes of developing arts-based interventions for children experiencing adversity), but more importantly, it gave me a family in South Africa. I have started meeting them virtually more regularly, and initiatives, such as me facilitating a mentorship program for the boys and coordinating resources for international scholarships for all of them to attend the University of Toronto if they want to, are on the horizon. I am also excited to share that I am currently in the process of trying to secure funding so that I can, not only return to SOS Cape Town this December to resume my programming, but, with on-going discussions at SOS Headquarters in Europe, to potentially tour my intervention to any of the SOS locations around the world, which are stationed in over 130 countries. Zama is even preparing a recommendation letter to advocate for my proposal, which I am extremely grateful for.

I said at the beginning of this report that I was concerned about burning out, so, for the children, I engaged in 100% self-care on weekends. However, these youth that I worked with made me realize that I deserve to be the reason that I take care of myself. I would always roll my eyes whenever I would hear adults mention something like “I went to help the kids, but they were the ones who ended up helping me”, but now I really get it, there’s something magical about getting in touch with children from a different culture who wholeheartedly accept your silly little improv intervention idea. I wish I could have done so much more, but I am proud of what happened—now I just need to find a way to meet Ariana Grande so that I can really make all of their day.

.jpg)

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to the Laidlaw Foundation for trusting me with my ambitious ideas and funding my journey throughout; thank you Susanna Kempe for suggesting that I reach out to SOS. I am also grateful for the University of Toronto Laidlaw Scholars Program in particular for taking care of many details in preparation for this 6-week adventure—your enthusiastic encouragement was so appreciated. I also want to thank Sipelile Kaseke from SOS who responded to my cold email with kindness and curiosity—my project would have never happened if you did not open that email. Thank you as well to Zama Mbele from SOS—you are such a strong, powerful, passionate person who truly cares about children’s well-being; I learned so, so, so much from you. I also need to thank my right-hand man, Alois Aloo, who is the youth coordinator from SOS, who not only came to every single improv class, but ended up performing (and crushing it!) in our final comedy show; you modelled such positive outlooks on my project and set me up for success with the teenagers—it was an honour to work with you, you will always have a brother in Canada now (It was also incredible that we found common ground even though I’m an Arsenal supporter and you’re a Manchester City fan!). Finally, and most importantly, I want to thank all the teenagers who participated in this intervention and constantly made me fall to my knees while uncontrollably laughing—ek is lief vir jou!

![[Closed] LiA Opportunity: SOS Children's Villages Cape Town – Summer 2026](https://images.zapnito.com/cdn-cgi/image/metadata=copyright,format=auto,quality=95,width=256,height=256,fit=scale-down/https://images.zapnito.com/users/647804/posters/9db789af-7f05-417f-ab56-098d23e845d5_medium.jpeg)

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in

What an incredible reflection! It's amazing that you were able to develop an intimate connection with your students through comedy, and that you and your work had a such a clear tangible impact on the students' lives. I also appreciate that you want to build lasting partnerships with SOS Children's Villages that extend well beyond your LiA. I hope you can secure funding to go back to Cape Town to continue this work!

Thank you so much, Trisha! I really appreciate that you've supported my project since my very first weekly log about it here on the network. I am equally excited for you and the positive impact you had in your LiA project in Tanzania. Thanks again for your kind words!

Every time I read an LiA reflection I think I cannot be more impressed or moved, and then I read this. And tbqh, I am a mess. Typing in tears is really not ideal. From setting such thoughtful SMART goals including prepping from January through to refusing to take the easy option and cancelling the show, you have demonstrated not only how to make the most of your LiA experience, but also how to give and grow the most; in short, how to be a good leader. I am so delighted that you had such an amazing experience; obviously for you and for SOS, but mostly for those students whose lives you have changed forever. I am so glad SOS want to roll out your work. Perhaps you can coach some Laidlaw Scholars to go next year and continue your incredible work.

Thank you so much for these extremely kind words, Susanna—I really appreciate it! Your support throughout has been so appreciated, and I am very grateful.

As you know, dear Youness, the wonderful thing about improv is that we always say, «Yes, and…», acknowledging and accepting what has gone before (never refusing a proposal), and building on it, taking a step forward and creating a springboard for the next line in the scene. What you describe in your report as the ‘irony’ of using improvisation skills to rescue your show is a testament both to the power of improv as a performance art but also to the transferability of the skills you master and teach so enthusiastically. Young people who can improvise on stage will go away with so many useful competences for their future lives: positivity and respect, flexibility and resilience, trust and courage. By the way, I have used Emotional Quadrants in improv myself. While reading your report, I began in the ‘curious’ quadrant, walked through ‘amused’ and ‘impressed’, and finished the journey ‘deeply moved’. Thank you for sharing your experience, and for your support for SOS Children’s Villages.

Wow, thank you so much for your supportive words, Marc! If there was an ideal takeaway that I wanted readers to have from my report, it is exactly what you described. I am so grateful to connect with open-minded individuals like yourself who understand the possibility of using comedy to support child development.