In Defence of Anthropological Fieldwork in (Single Player) Video Games

In Defence of Anthropological Fieldwork in (Single Player) Video Games

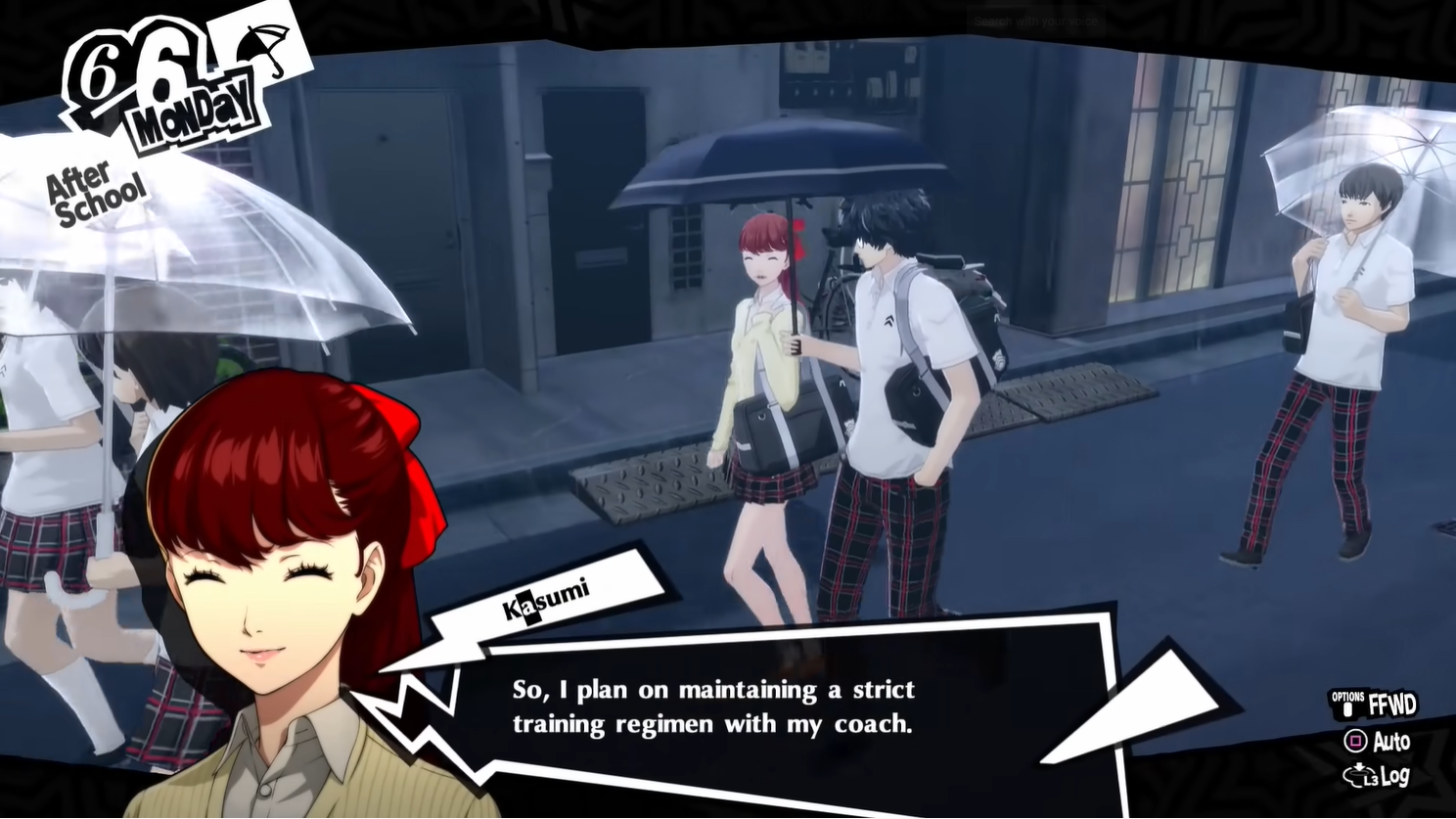

The player-anthropologist-protagonist walking and chatting with his friend, Kasumi Yoshisawa (芳澤 かすみ) - one of the many examples of social relations in the Japanese Role Playing Video Game, Persona 5 Royal (Persona 5 Royal 2020).

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Triangle, R2, R1, X, R2, X – the buttons have almost become second nature to me as my fingers fly over the PlayStation 4 remote controller during my fieldwork within the virtual world of Persona 5 Royal (P5R)– considered as one of the best Japanese Role-Playing Video Games of all time. From the outside looking in, my actions may be confusing as people may not understand why playing video games is an anthropological endeavour. This is a reasonable question as most anthropology on video games focuses on how players and game developers interact with video games in the 'real' world. In this blog post, I will briefly outline why I am conducting fieldwork within single player video games for anthropological studies.

Why are video games a timely topic?

Earlier on in the COVID-19 period, a pandemic with a ‘beginning’ but perhaps no end in sight, many media outlets jumped on reporting the wider trends of people socialising in video games – whether it is the celebrated chill game, Animal Crossing: New Horizons or the murder mystery party game, Among Us. Playing online video games as a way of hanging out has moved away from the supposed purview of teenage boys playing games like League of Legends, FIFA, or the Call of Duty series to the mainstream.

A good example of this push of video games from the margins to the mainstream is the many video game content creators, such as Dream and Valkyrae, that have become bonafide celebrities during this period. Because of the large number of young people that has been limited to the confines of their home during this period, many have turned to livestreaming platforms such as Twitch or YouTube to pass the time. Video game content creators and the industry at large have capitalised on this previously untapped audience. Echoing the rise of YouTube celebrities in the 2010s, these new age content creators – and their communities – have made an undeniable mark on the popular culture landscape of this time.

Finding social relations in video games.

Although, my academic interest in the digital began with the consumption of video game related content and loosely participating in associated communities, it is not the virtual communities that are built through and around video games that I find the most interesting. What I find more exciting is how virtual worlds, such as video game worlds, can be considered as social.

Social relations in virtual worlds warrant a closer look especially in a time period where our relationships have mostly been facilitated through screens.

This direction in anthropology is not a novel one. In Boellstorff’s seminal book, Coming to Age in Second Life, he conducts two years of fieldwork within Second Life – a large virtual world where people create avatars and hang out in communities. Throughout his fieldwork, he creates and embodies as a virtual anthropologist avatar, Tom Bukowski, to understand virtual world. Boellstorff’s rationale for studying virtual worlds is that they function not just as mere representations of society, but rather where ideas about identity and society are shaped by its many inhabitants. Thus, by using anthropological methods to study virtual worlds, we are recognising that virtual worlds are social. Social relations in virtual worlds warrant a closer look especially in a time period where our relationships have mostly been facilitated through screens.

The case for the anthropology of single player video games.

Along a similar vein, my Laidlaw-funded research has focused on how relationships are constructed and maintained within the single player video game’s world of P5R. Not unlike relationships built in virtual communities with ‘real’ people, the people (or characters) in the video game’s world form relationships with social intent. While this social intent may be encoded within the game’s narrative or logics, it is still beholden to histories of the world. The people, within the game, experience and inhabit these histories when they express social intent. For example, as a player-anthropologist, I am not just talking to a non-playable character who merely advances the game’s narrative, but rather a homeless man in P5R’s Shibuya… who’s dreams, and aspirations were crushed by the uncaring society we find ourselves in.

Through playing the video game as fieldwork, we can utilise anthropology’s rich methodological repertoire to understand how people think and act within the video game’s world. This may in turn inform us of how people think and feel in specific place and time period such as 2010s Japan in relation to P5R. Fieldwork within single player video games can be considered as another way for anthropologists to understand human societies in all its layered complexities.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Do you agree with my thoughts on the anthropology of (single player) video games? Please comment if you have any thoughts about the article. and feel free to contact me for a chat about the anthropology of video games, my research project, or my Laidlaw experience.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in