The Matter of Size - Week 3

Flies can be found everywhere. Fungus gnats are a well-known threat to indoor plants, fruit flies are a nuisance to deal with when there is food waste that was not thrown away in time, and mosquitoes are menaces that make one itch for days at a time in the summer. Who knew that studying pests through a microscope would become a hobby? Not me, although my high school biology teacher was not surprised when I told him the news.

It has already been three weeks since I have began dissecting flies of all sorts: big and small, young and old. My hands no longer tremble and my heart beats at a steady pace as I cut into the tissue.

I was amazed (to say the least) by how unique each larval and pupal form of each species is. This uniqueness meant that for each specimen I had to devise different dissection techniques.

Fungus gnat larvae have a thick cuticle which cannot be cut through due to its softness, meaning that I have to leave them as tubes by cutting off the tail and the thorax with the head attached. The fungus gnat pupae, on the other hand, have a harder cuticle, allowing my scalpel to swiftly slide from the head to the abdomen, exposing the inside tissue.

As for the mosquitoes, I take any cut tissue I get. Why? The bloodsuckers-to-be, in both their larval and pupal forms, move on the slide. One would think that beheading them would solve the issue; however, as many dissections have proven, their long abdomens continue to wriggle long after the fact. Hence, I cut whichever way I can position my scalpel.

After I gently transfer all of the cut tissue into 4% paraformaldehyde for fixation, I am left with the remains of the battle that had just taken place. Heads, tails, guts, and organs lay strewn about. Flies that could have been pestering me in the kitchen and feeding on my blood have been wiped out of existence in a matter of minutes, with their successors and relatives destined to follow the same fate.

The procedure to clean the mess is clear: use a tissue to wipe off any remains and throw it away into the biological waste bin which will be autoclaved. I use PBS to wash the slide and after that, it is as if this has never happened.

As I clean up the desk after a day's work, it is difficult to not think of ethics, as invertebrate research does not currently require any approval, in addition to what is going on in the news. The parallel is wild, even outrageous, and yet, it is horrible to think that the way I treat flies is the way some humans actively choose to treat other humans.

I also keep on thinking, is dissecting flies for research purposes enough of a justification? At one of the most recent dinners with a few other Laidlaw scholars, who have become my closest friends, the topic of religion came up. Indeed, in many religions, it is considered immoral to kill any being, no matter the size. One such religion is Jainism, where there is a strong emphasis on non-violence (Ahimsa) as well as the minimization of harm to all beings. In what position does this put me in? It is a constant dilemma, a constant debate, a constant argument in my head. So far, I have found no answer.

Would I be able to do this as calmly if it was a vertebrate, a mouse perhaps? No, I shudder at the thought. But then, what separates a mouse from a fly? After all, they both live and breathe and procreate. This then makes me think about the culture I was raised in, because, as far as my imagination goes, if I was raised in a Jain community for example, I assume that my conscience would not allow me to do what I do now. In my culture, however, whilst I was discouraged from purposefully and intentionally inflicting harm upon others, it was more the (what some evolutionary biologists would call) 'higher' organisms, as killing mosquitoes and ants, the 'lower' organisms, was encouraged if there was a direct confrontation.

The now outdated Great Chain of Being [1], a religious-like hierarchy in organising organisms (with God at the top and inanimate objects at the bottom), continues to influence the modern perception of scientists regarding taxonomy and animal classification (exemplified by the vocabulary terms 'higher' and 'lower' when describing organisms). It would be incorrect to not point out that such terms help explain the biological 'complexity' of the organisms in a simple manner, because the complexity does tend to increase from older to newer species. Nevertheless, it can also be highlighted that such terminology, both consciously and unconsciously depending on the context, influences how we perceive the value of an organism's life. I am guilty of this, because my research does and will involve classifying the flies in relation to one another using the 'height' scale. I believe that it is not possible but also not necessary to remove this new hierarchy from our lexicon, but, there should be a wider and heavier focus on reframing of the value the science community assigns to organisms who cannot speak on their behalf.

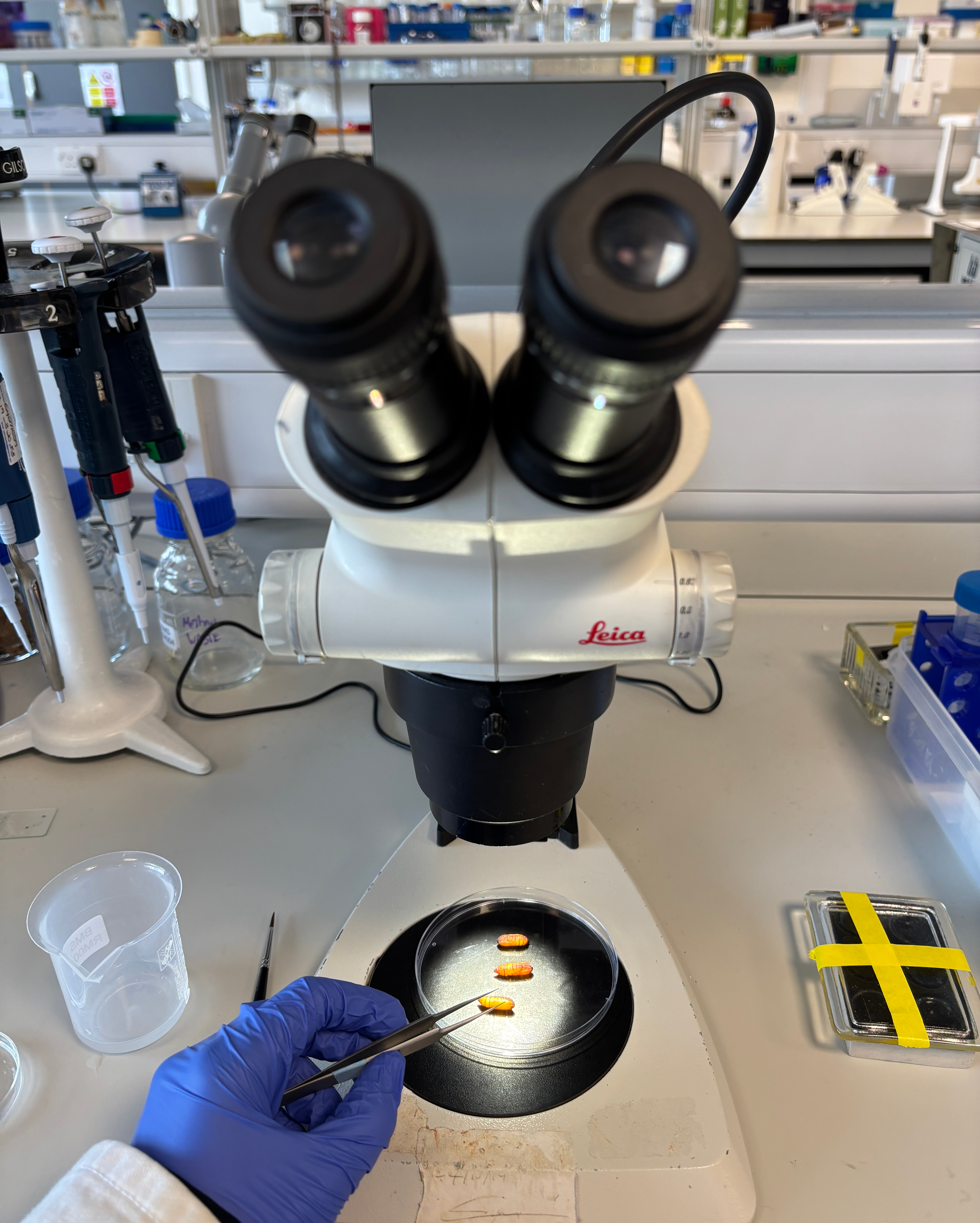

On one afternoon, when for a change I decided to dissect moth pupae and larvae, who were large and fragile, I immediately felt more guilt, particularly when I failed to correctly dissect the first larva and pupa that I cut into. My hypothesis is that it was the size, with my brain, unbeknownst to me, using a size benchmark to build my perceived value of an organism (disclaimer: I am not a neuroscientist). Using size as a measurement of worth is a useful neural mechanism that has certainly played a major role in the survival of the humanity, especially during the time when we had to be hunter gatherers (*proceeds to give a neurobiology hypothesis*). Yet, it would be wrong to rely on it as a moral compass in important decision-making that involves other lives (deontologists and utilitarians have long had a field day arguing about whether the ends justify the means but that is a topic for another time).

Figure 1: Preparing for the dissection of moth pupae.

After such deliberation, I suppose that my primary conclusion is that the rising implementation of the three Rs (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) [2] is bringing biological research a step closer to being more moral and ethical. Furthermore, to reach the gold standard, it is not enough to adjust the regulations and rules. Though challenging and possibly unattainable, there needs to be a collective and holistic effort on adjusting the perceived value of life.

References

[1] Clarin, Laurence (2000) ‘Leibniz’s Great Chain Of Being’, Studia Leibnitiana, 32(2), pp. 131–150. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40694364 (Accessed: 25 June 2025).

[2] The 3Rs (no date) NC3Rs. Available at: https://nc3rs.org.uk/who-we-are/3rs (Accessed: 25 June 2025).

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in

I really enjoyed reading this Alexandra. Thank you for sharing your thoughts, i think this is a really important thing to consider and talk about!