Same Old, Something New? - Week 4

It has been four whole weeks since I officially started my Laidlaw research and — surprise, surprise — nothing major has yet been discovered (insert audible gasp). This piece of knowledge that is common to researchers who have been in the field for a long time is only dawning upon me now. To properly discover something and have enough data to not only support but to also serve as concrete evidence for the discovery takes a lot of effort and a long time, something which I do not have.

Entering the Laidlaw research period I was confident that I would end the summer with a proper research paper of publishable quality in the workings. But, as my progress is indicating, this will very likely, if not definitely, not come true.

I, like many eager undergraduates, entered university with big goals: get a paper published before I graduate, do 2-3 internships, get a first in all of my modules, and so on and so forth. This is a familiar and common sentiment shared by many who want to make a contribution to their respective field and hopefully secure a satisfying job. But, unlike a decade or so ago, the entry standards are getting more and more unachievable for the majority of graduates, thus also raising the stakes and the pressure to excel.

It is interesting to see how this pressure accumulates over time: one day you are working in the lab and then you blink and suddenly it seems that you are falling behind and that you will never catch up and that the work keeps on growing until you are looking at the ceiling thinking, "What in the world is going on? Have I failed?". No one has ever said that I need to publish a paper during my undergraduate degree directly to my face. And yet, this expectation has been planted in my head by what I see on online platforms, with LinkedIn being one of them. By saying this I do not in any way mean to tear anyone's achievements down or to criticise those who were able to accomplish something so admirable so early on, but the problem with the online world is that no one gets to see how much work it takes to get to that point. Viewers can usually only see the end result.

I found out from a PhD student who works in the same lab as me that those students often work on those experiments for two years before being able to gather all of their outputs into publication-worthy material, making it a rare phenomenon. Moreover, she pointed out how even at the PhD level, the dependence on living organisms to behave the way we, the all-knowing and omnipotent scientists, want them to in biology means that the majority of biology PhD students get to publish only 1 research paper at most (imagine my surprise when I found out that oftentimes biology PhD students do not publish any research papers during their degree). In mathematics or physics, on the other contrary, it is expected that the PhD students publish at least 2-3 papers before the completion of their degree because, (insert dramatic drum roll), they can work without the restriction of growing organisms or culturing cells that very frequently decide to do their own thing without asking first (I mean, how dare they?!), although of course they have their own challenges.

It is easy to get carried away by pipe dreams and by embedded notions of what we need to achieve in order to be successful, remarkable, phenomenal, distinguished, ground-breaking, and all the other terms used to describe the great, important figures that have left a mark in history. But then again, how and in whose eyes?

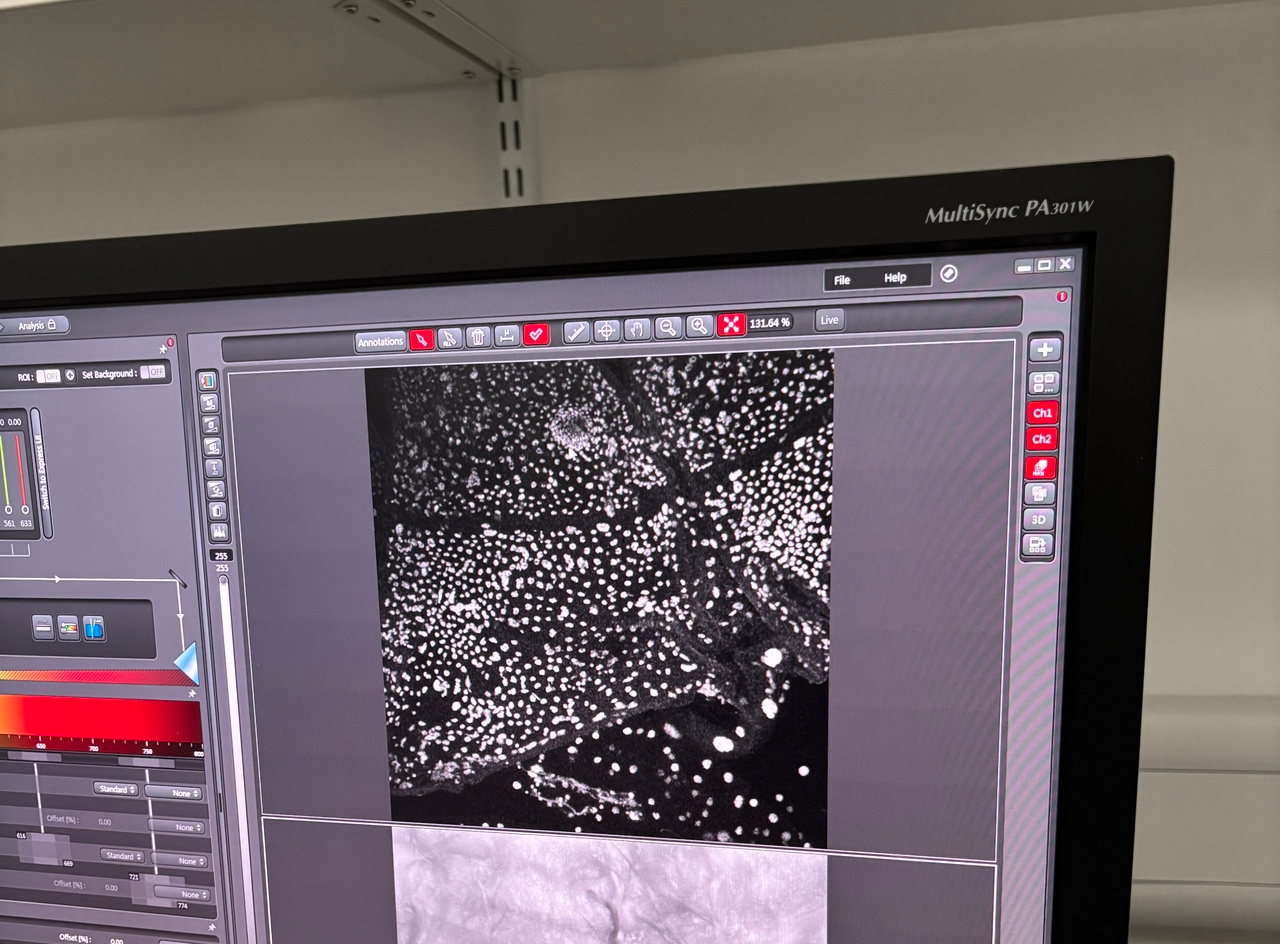

My roman empire is the quotation by Soren Kierkegaard, "Life is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be experienced". On Friday my supervisor and I went through all of the slides I prepared over the week and it was a wonder to behold the variety of cell nuclei sizes and cell types shown on the bright screen of the computer. As we were looking through the dissected tissues and figuring out what was going on, it suddenly dawned on me: I am the first person in the world to look at how cells look like during development in mosquitoes and fungus gnats. Based off of everything that we have captured, it appears that development in fungus gnats is much more complex than in mosquitoes and is more closely related to metamorphosis in D. melanogaster than we would have initially thought. However, to understand the full picture, I still need to dissect many more fungus gnats. As I was there in that dark room sitting by a large confocal microscope and the fluorescent cell nuclei shining on the screen, I was finally able to fully appreciate the work that it took to get to that moment. Sure, I do not have all the answers or all the data that I would have initially liked to have, but 3 weeks ago I would not have been able to dissect the tissue even close to the skill with which I am able to now.

This will sound exactly like the ending to any 2000s teen movie but maybe I am behind, and maybe I am not. Maybe there is no such thing as being behind or maybe everyone and everything always runs behind chasing a more perfect version of the present. All I know is that I am so grateful for the opportunity to be studying something completely new and, in addition to that, experiencing the slow but sure growth as a researcher. Treating development in flies as a problem to solve and a task to conquer in the name of a research paper invalidates all of the other beautiful and equally as crucial aspects of research, so, my takeaway is that I need to let go and just follow along the trail that my data is paving without any expectations. It is difficult to release hopes that you used to hold so tightly, especially when it felt that they were only a couple of centimetres out of reach; however, it is for the best. The outlook I choose to take is that all good things come in their own time so presently I can sit in my chair looking out at the lengthening night and simply savour the moment whilst thinking about how I will be managing next week with my supervisor gone.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in