Starting my LiA Project - 3L Place, Adult Developmental Disability Living Center

When I began my Laidlaw project with 3L Place, I expected to learn about accessibility in medicine, but I didn’t realize how often that learning would begin by questioning the assumptions I had taken for granted.

In premed spaces, we often talk about “patient-centered care” as a guiding principle, but working with neurodivergent adults—especially those who are nonspeaking or have high support needs—has pushed me to consider what that phrase actually demands in practice. It is one thing to say care should be centered on the patient, and another to confront the reality that many clinical environments are structured in ways that inherently exclude those who communicate, process, or experience the world differently.

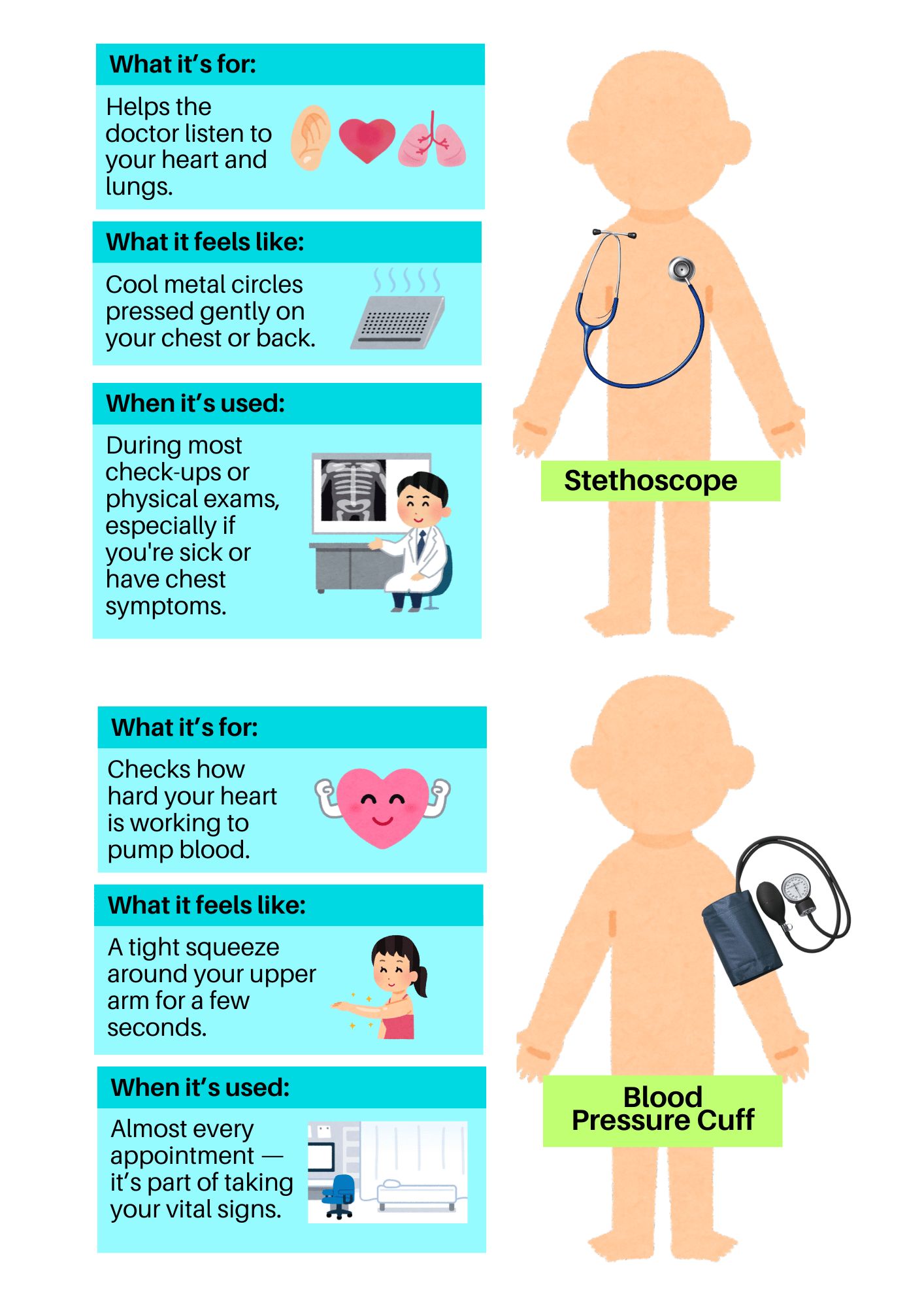

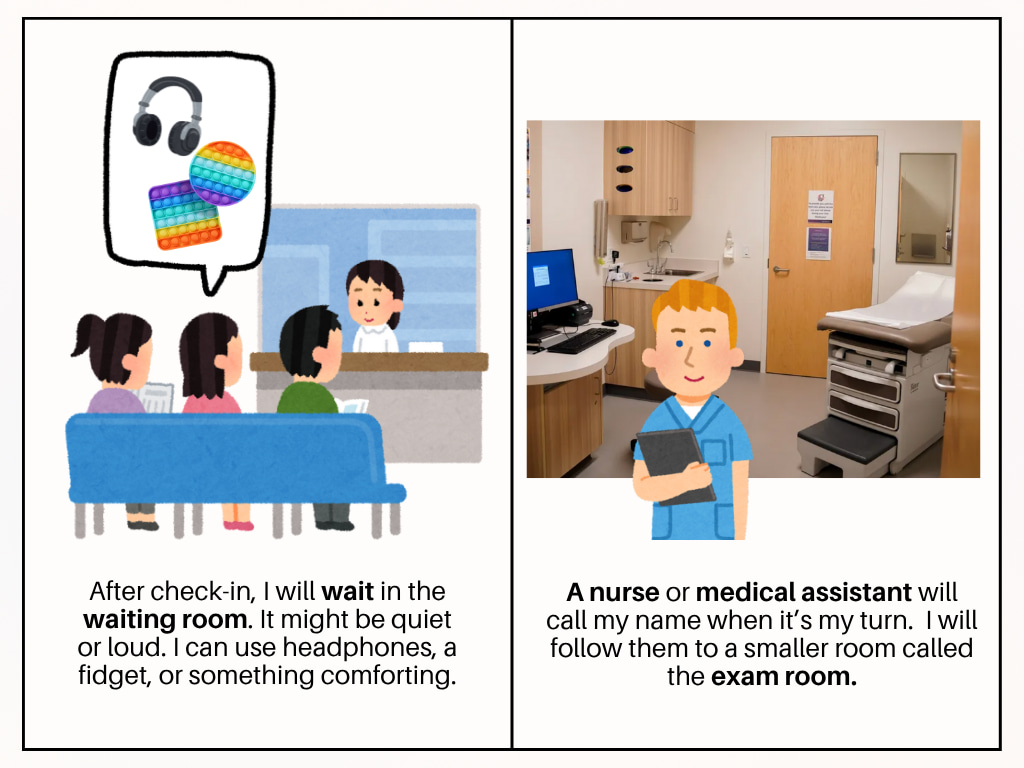

Through this project, I’ve been developing personalized medical passports and social story-based toolkits designed to help neurodivergent adults advocate for their needs during medical appointments. These materials translate complex systems into more digestible formats while also helping providers understand a patient’s communication style, sensory preferences, and support needs. What has become clear, however, is that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to accessibility. What feels empowering and clear for one person may feel infantilizing or reductive to someone else, and honoring autonomy means allowing for those differences rather than flattening them for the sake of standardization.

As I’ve moved through early stages of design, I’ve started to see that accessibility is less about checking boxes and more about cultivating a mindset of openness, adaptability, and genuine curiosity. Leadership in this context has not looked like taking charge or having all the answers, but instead has required me to listen more carefully, ask better questions, and recognize the limits of my own perspective. It has meant making space for feedback that challenges my assumptions and allowing the people I’m designing for to shape the process directly, not just react to a finished product.

This project has already begun to change the way I think about care—not just as a clinical goal, but as a shared interaction shaped by power, trust, and communication. I am learning that to truly design for dignity, one has to begin by seeing the whole person behind the patient chart, and by creating tools that affirm, rather than flatten, their complexity. That is the stance I hope to carry with me into the rest of this project, and eventually, into my training as a physician.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in