Redefining Structural Injustice - Summer 1 Blog Post

When I set out, my vision for my Laidlaw research project was that I would step in to political philosophy, take one well-defined concept (‘structural injustice’), fit it in to a well-established theoretical framework (human rights theory), and be on my way. In reality, conducting this kind of research was far more challenging than that, and I learnt a huge amount from the experience – both about political philosophy, and about myself as a researcher. Along the way, I started to develop (what I hope is) a useful and more coherent way of thinking about structural injustice, and I gained a newfound appreciation for the importance of doing political philosophy.

It took only two weeks of literature review for me to become totally convinced that I needed to revamp my entire project because the traditional way of thinking about structural injustice had it all wrong. On the traditional account, it seemed incredibly difficult to actually explain what makes structural injustice ‘unjust’, not just ‘bad’. Now, part of the challenge of trying to understand concepts or arguments in political theory is that if they don’t seem to make sense it’s often hard to know why that is. Sometimes it’s because you haven’t read enough of the literature. Other times, it’s because you don’t fully understand what you have read. Other times again, it’s because the concepts or arguments themselves are fundamentally lacking. At that point in my project, I think all three of those things were true. I hadn’t read enough, and my understanding of the concept wasn’t accurate enough – so my first attempts to explain that weakness in the canonical conception fell flat.

I’d spent a week working on that, so realising that I’d failed to explain the problem I saw in the traditional conception was a difficult thing to realise. But it was important to do so – not only did it mean I could return with a new, much more promising approach, but I also learnt a lot from the experience of having to respond to a setback like that.

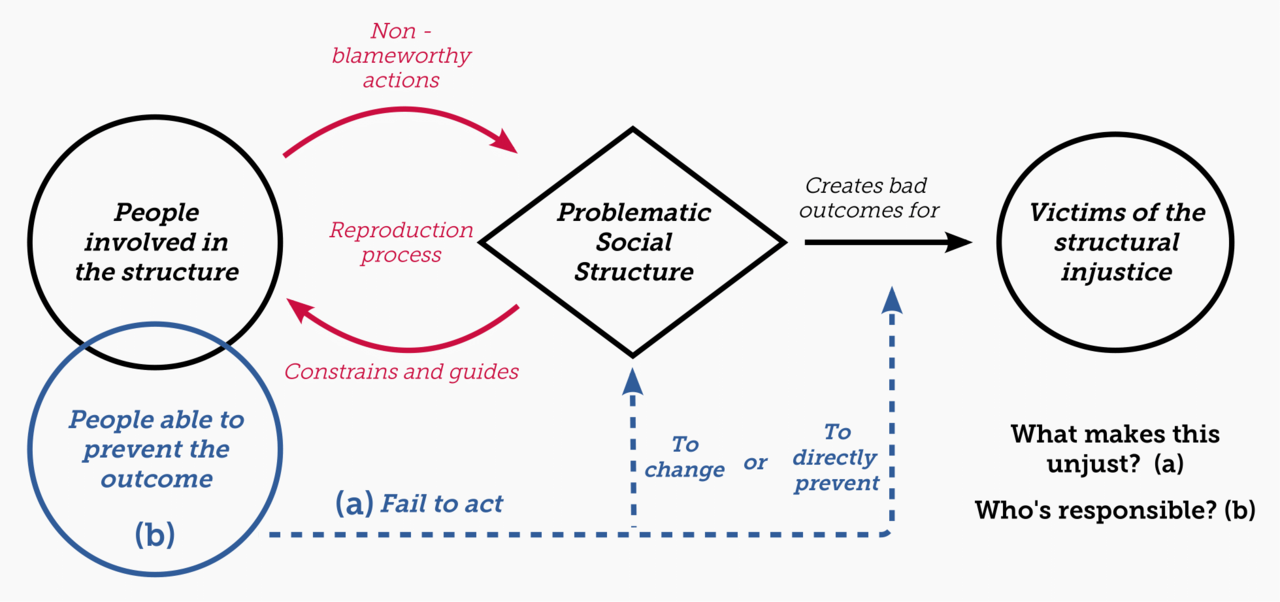

I came up with a better explanation of why the original approach doesn’t work – and alongside it, I started to develop a new, alternative theory to explain what ‘structural injustice’ is and who’s responsible for it. In essence, I suggest that structural injustices exist when a sufficiently bad outcome of a structure could reasonably have been prevented, but wasn’t. Hopefully, this alternative manages to avoid the problems which plague the ‘canonical’ way of defining structural injustice, while still preserving the usefulness of ‘structural injustice’ as a concept.

I’d arrived at a way of understanding structural injustice I was happy with – but I simultaneously realised that I did not have the time or the understanding of the human rights literature to bring human rights theory into the picture too (which I’d hoped to do at the start). This is a challenge I hope to address in future research – right now I’m focusing on writing a paper to exposit and defend my alternative conception of structural injustice.

In political philosophy, theories like this are tested not by data, but by arguments – arguments which question their assumptions, challenge their logic, or reconsider their conclusion. So far, my ‘tests’ suggest this theory is promising; of course it needs testing further. If it works, I think there is substantial potential for future research to demonstrate that structural injustice can be brought together with human rights theory – an exciting prospect, given that human rights are such a uniquely powerful moral and political tool. This is research I’m excited to embark on, if I get the chance.

I’m delighted to have come up with an idea that seems promising and could help us better understand structural injustice. But when other Laidlaw scholars were researching heart stents or gathering data on femicides, it was impossible to avoid questioning what real, positive impacts my research was having. I know that political philosophy can come up with words for things and ways of thinking about things that we didn’t have before, which can be invaluable. But even so, the link between hours of work I put in and concrete benefits for peoples’ lives would be incredibly indirect. The more I thought about it the more I became frustrated by this fact. But political philosophy doesn’t necessarily just produce useful concepts etc – doing political philosophy and thinking about political philosophy (even if we don’t realise we’re doing so) changes our perspective. Thinking so much about structural injustices has genuinely increased my commitment to giving to good causes, and made me change my priorities for the work I do later in my career. I can only hope that the more I talk about structural injustices to others, the more they will change their perspective too. That might not be quite the same as designing a heart stent – but there’s a place for both.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in