Reach for the stars: how astronomy and astrophysics are moving into a new era

A not-uncommon topic of conversation amongst university students is about how we ended up studying in our current areas. For me, an astrophysics student, I owned my first telescope when I was a young child, and have always been fascinated by space (as a lot of kids are). For many of us studying this degree, I suspect this is where the journey starts, similarly to how it would’ve done for great astronomers of the past – by looking up. But that, it seems, is just about where the similarities between past and present end.

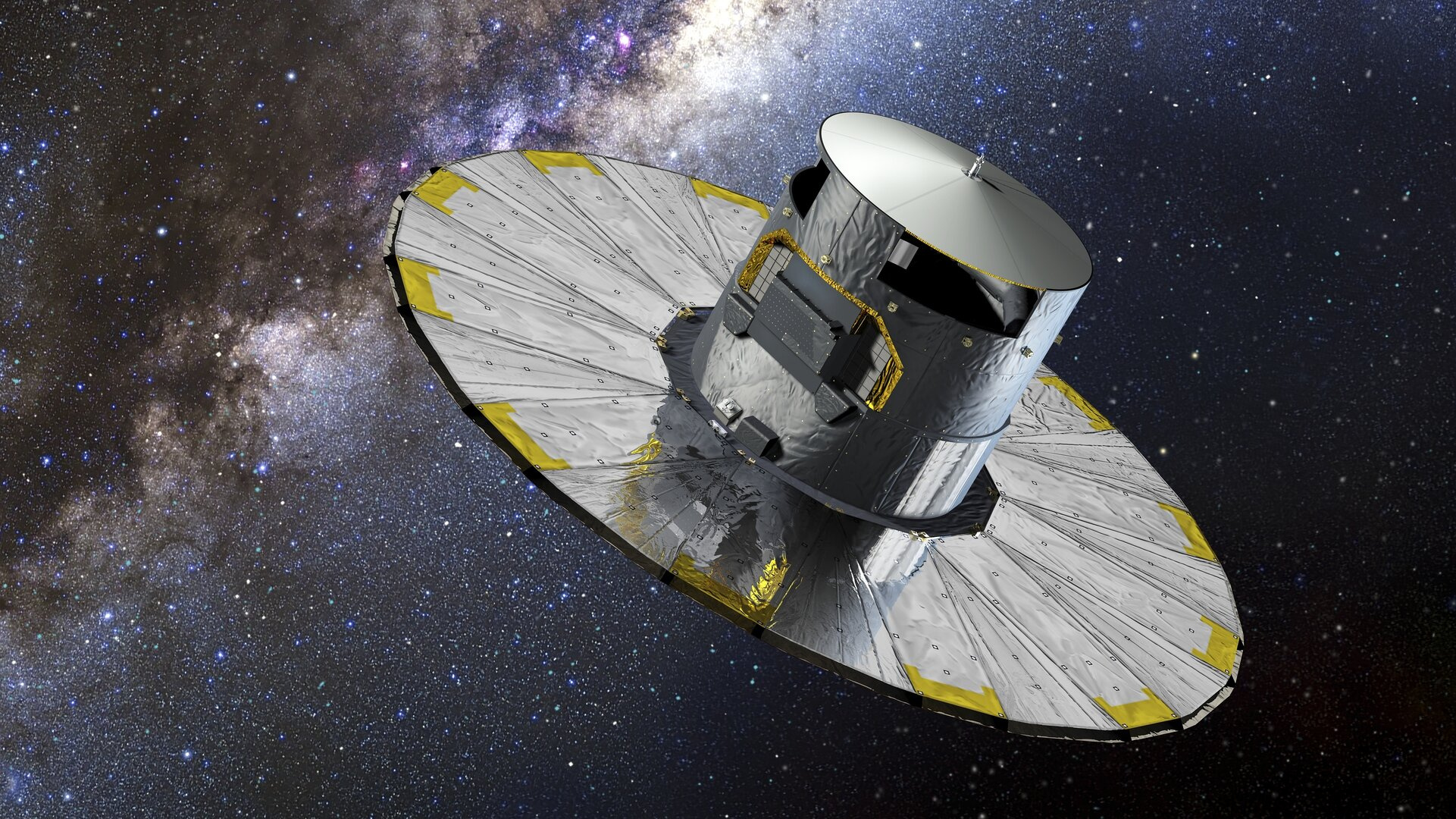

Rather pedantically, I shall weave into this blog post a small discussion on the difference between ‘astronomy’ and ‘astrophysics’, or at least how I perceive them. To me, astronomy has more connotations of looking up and observing the cosmos, the quality of which has improved massively over the years, predominantly through leaps in engineering. Perhaps the most famous recent example of such an upgrade was the much-awaited James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) – the successor to Hubble, heralding a new era in observational astronomy. JWST may have stolen the show, but my project involves a more humble superstar, launched in 2013: the Gaia satellite.

Gaia was launched as a flagship mission of the European Space Agency (ESA), with the goal of providing extremely accurate astrometry (primarily positions and motions, but also distances) for almost two billion stars both within and beyond our Milky Way 1. My project focused on using this data to map a star-forming region in the Monoceros constellation, looking specifically at stellar clusters and associations (groups of stars moving together). Once these clusters are found, analysis can then be performed to look at the ages of these stars, and the historical star formation rates in the clusters.

This analysis stage is where most of the astrophysics comes in – applying our knowledge of space and physics to analyse and solve problems related to these observations. This has also become much more powerful, particularly in recent decades, with advancements in computing. The real challenge lies now on the astrophysics side – with all these new, stunningly accurate telescope observations being sent back to us, how can we possibly perform the meaningful analysis on datasets which often contain hundreds, thousands, or even sometimes millions of objects?

Well, that’s the one thing underlying every step of my project. The means by which I fetch my data is via code. The plotting and visualisation of data is via code. The analysis of the data? Also via code – a tool which I wouldn’t have had this access to even just 50 years ago. The perception that astronomy is ‘looking up’ at cool things in the sky, despite this still underpinning it all, is actually far less prominent in the day-to-day life of someone doing research like mine. The truth is, I could have done the vast majority of my project in my pyjamas and in bed, needing only my laptop, the magic solutions to my problems that exist on the internet and an endless supply of food (particularly chocolate) to keep me going. Oh, and possibly a wall to bash my head against from time to time.

New up-and-coming astronomical surveys are continuing on this theme of code and data. The Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) will map over 40 billion objects and collect over 100 petabytes of data 3. The scale of this is almost too vast to comprehend. Just one petabyte is apparently broadly comparable to “500 billion pages of standard printed text” 4. But that’s obscene to visualise – perhaps a better way is comparing it to recent surveys. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) was a massive project conducted over a period of time longer than a decade. LSST will be collecting the equivalent amount of data as SDSS every single night.

Astronomy and astrophysics are therefore moving (and moving fast) towards an era of big data, where the requirement to be a competent data scientist is almost as crucial as being a competent astrophysicist. Both areas are inextricably linked: astronomy relies on astrophysics to obtain meaningful results, yet the astrophysics would be impossible without the underlying astronomy. Yes, we always need to keep looking up, with new telescopes being able to see further into space and time than ever before, but the large amount of data we collect is only as good as the people and algorithms used to infer meaning from it.

I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr Paula Teixeira, and the St Andrews Laidlaw Team for helping me with this internship, as well as the Laidlaw Foundation and Lord Laidlaw for giving me this wonderful opportunity.

[1] ESA, https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Gaia

[2] ESO, https://www.eso.org/public/images/eso0848a/

[3] Connolly and Ivesic, Astro-statistics and Machine Learning course

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in

Great insights! Looking forward to seeing your work!