LiA Reflection Week 2.5: Asylum and CBP

This blog builds off of experiences from previous blogs. It may be helpful to read the previous ones: Week 1, Week 2.

Geographical Orientation

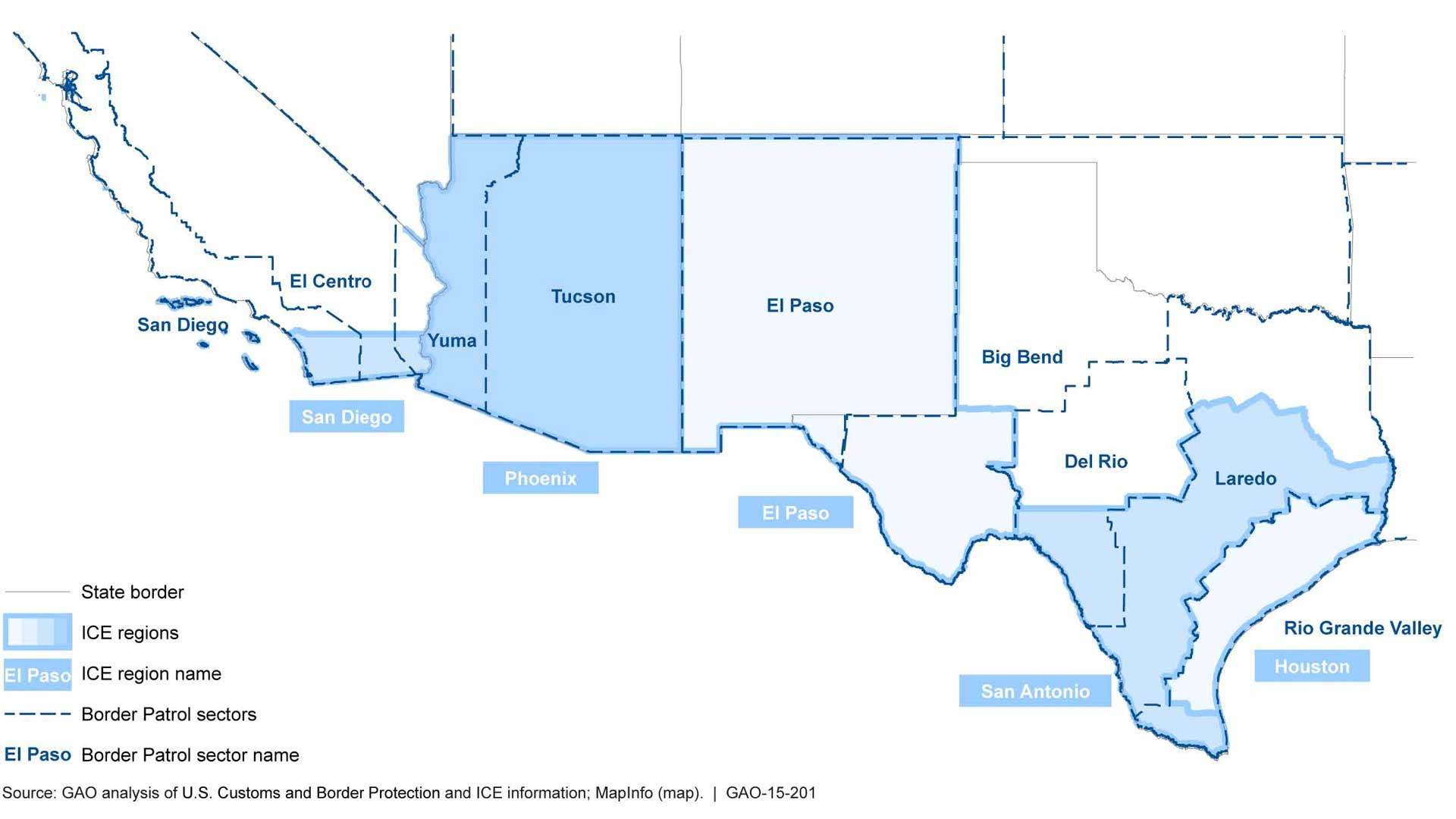

I realized that while I have described a lot of locations in Southern Arizona, I have not given a clear idea of where along the border these places are. My experience in the Borderlands was focused on the Tucson Sector. That is a label given by Border Patrol to this region and refers to the area of jurisdiction roughly between Ajo, AZ, to the West and Douglas, AZ, to the East.

In my first blog post, I spoke about the Tohono O’odham Nation, which is towards the Western side of the Tucson sector. Ajo, which I discussed in Week 2, is past the Tohono O’odham Nation.

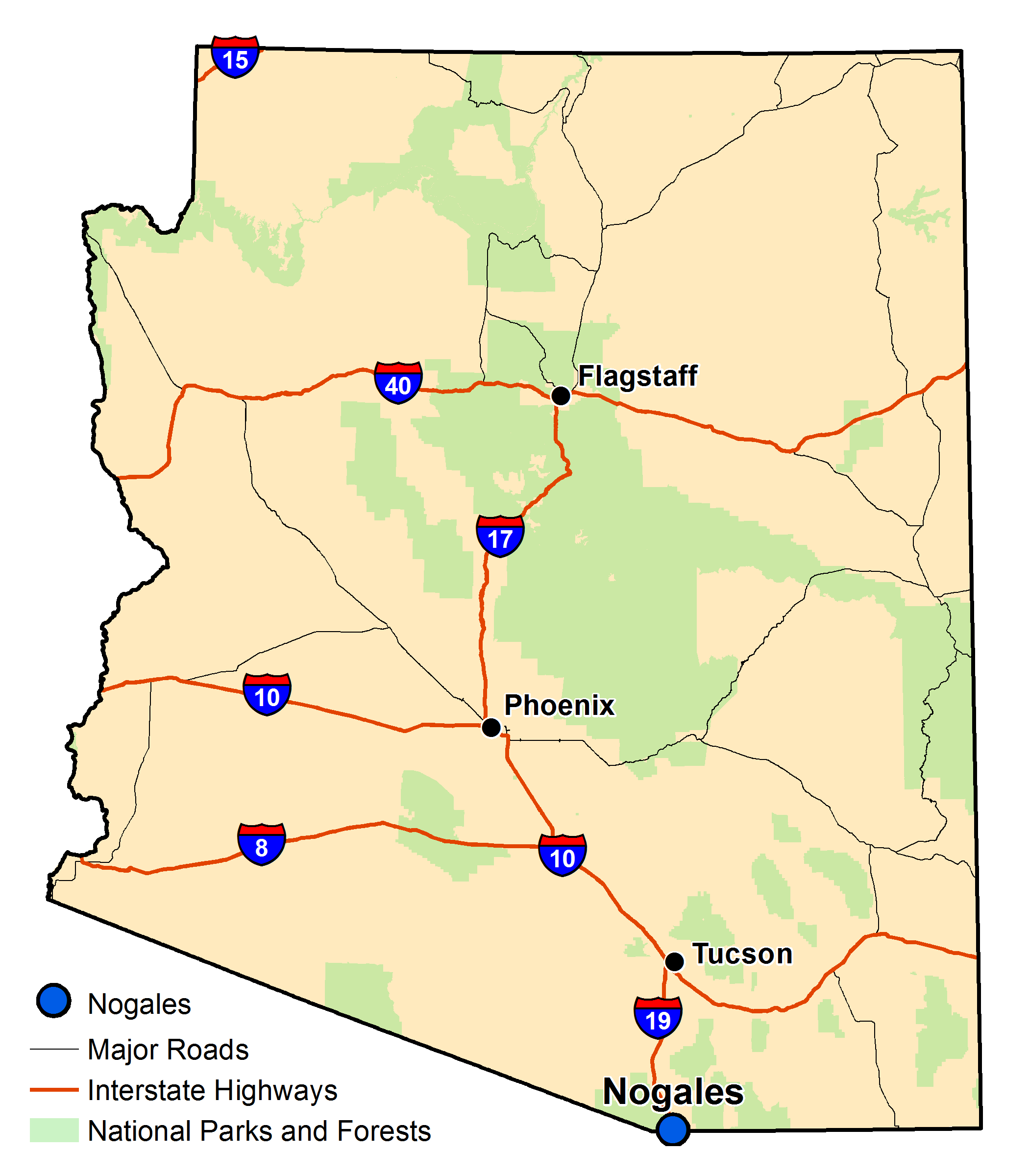

My cohort stayed in Tubac, Arizona, which is where the Border Community Alliance is based. Tubac is just north of Nogales, which is the primary location we spent time in. Nogales is considered a sister city that includes Nogales, AZ and Nogales, Sonora. Much of our time will be spent around the Nogales Region.

In this blog post, I will also mention Lukeville/Sonoyta. Most border towns will have a US and Mexican counterpart. At the Lukeville Point of Entry, that counterpart is Sonoyta, and these cities are towards the Eastern side of the Tucson Sector.

Now that you know where we are, onto this week…

Waiting for Asylum

There are primarily two types of people who reach the border and cross without documentation: travelers and asylum seekers.

Travelers are people who may come to the border for a wide variety of reasons, although primarily economic, knowing that they likely do not have a case for asylum, or not having the resources to go through what legal means there are for immigrating to the US. These are the people who cross through the desert and try to navigate their way to the US undetected by Border Patrol.

Asylum seekers come to the border to seek protection from the United States due to having suffered or fearing persecution based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. To file for asylum, typically, one must step foot on US soil and then apply for asylum. If you have seen pictures of hundreds of people along the border waiting for Border Patrol to come pick them up, those were asylum seekers. There are several shelters in Northern Mexico that operate with the purpose of supporting asylum seekers as they wait for their asylum-seeking appointments.

However, when Trump came into office on January 20, 2025, he issued a proclamation that prohibited people on the southern border from seeking any form of protection. This meant that even people who had appointments that day were stranded and left to remain on the other side of the border.

As part of the BCA Internship Program, we spend time at several shelters for asylum seekers. This policy shift has made this year look much different from previous years, with far fewer people coming to the US border to seek asylum.

At Kino Border Initiative, which served as an extremely short-term shelter for asylum seekers, travelers, and deportees, we heard about how, in previous years, the shelter had been full of people and that they struggled to provide space for all of the people to stay. Now, the shelter sits jarringly empty.

I learned that Georgetown University has longstanding ties to the Kino Border Initiative as they are both Jesuit organizations. Kino, like many of the shelters we visited, is now considering its future and how to sustain itself given the recent changes.

They operate on a philosophy of dignity, compassion, and support. During our time there, we learned about the stories of migration that have come there. Many people migrate to the Nogales area due to violence in their communities, natural disaster, sometimes deportation. She explained that Prevention through Deterrence led to a boon for cartels, which we were told was a multi-billion dollar industry as it created a market for elicit crossings. She explained that if people attempt to cross illegally without a cartel, they will likely be killed. The US policies have created a business for Coyotes, often people hired by cartels and viewed as expendable, will transport people to the US. In the past, this has been through person al transport but now this has become more digitized, through sending gps coordinates and sending messages via social media.

We were told about the tremendous amount of grief among these people who are moving, whether asylum seekers or travelers. They suspect that despite decreased numbers of crossings and asylum seekers right now, there are still people trying to cross. They said, especially with the deportations happening now, some people who have lived in the US for decades are desperate to find a way to get back to their homes.

They said it could cost between $5,000 and $10,000 if not more to cross the border and travelers are often told that it’s a 30 minute walk from the border to Phoenix. In reality, this trip would be around 3 days if on walked without stopping. This walk would also be in the desert, and assumes that the individuals have clear directions on how to get to their destinations.

While many shelters have seen decreased use since January, that does not mean that there aren’t still asylum seekers in Nogales, Sonora waiting for U.S. policies to change.

Each week, my internship cohort will spend 1-2 days at our service learning placements: DEIJUVEN, Casa de la Misericordia y de Todas las Naciones (Casa), and Apartments with Voice from the Border (the Apartments). Casa and the Apartments are both spaces for asylum seekers to stay as they await their appointments.

While the number of people at Casa are much lower than they were last year, the length of time people have been staying there is much longer. Some of the people I spoke to said they had been staying at Casa for 15 months, many having had asylum appointments on the calendar when asylum shut down. These are people who cannot return to their homes due to the risk of persecution, and often cannot leave the Casa space due to safety concerns.

At the Apartments, several families share apartments which gives them a bit more independence as they wait for the chance of being able to live in America. The over a dozen kids staying there are able to attend school, but are unable to travel away from the apartments for many other purposes due to safety concerns.

These safety concerns are primarily cartels in the Nogales, Sonora region. While Nogales is a very safe place for Americans, it poses a high risk to travelers from the South who may have various physical differences from local residents. They are the most vulnerable to cartel action, since transporting people across the border or preying on more vulnerable populations is a very lucrative business as I mentioned above.

While these shelter programs are great initiatives for support and safety of these asylum seeking families, it is all clear the toll that waiting and the barriers to movement and freedom take on these families.

In the Lukeville/Sonoyta area, there is also a shelter we traveled to in Sonoyta, Sonora, Mexico, called Centro de la Esperanza. It was there that I especially felt the sense of the migrants feeling that they were living life at a standstill.

When I was at Centro de la Esperanza, I was slapped in the face with my privilege. I went there for just a few hours and was able to have some great conversations with people staying at the shelter. All of these people are asylum seekers who are waiting for the chance of being able to find safety in the US. Only some of the kids were able to attend school, and the ones who were would not be able to earn a diploma even if they are able to fulfill the graduation requirements since they are registered as observers. We were told that some of the kids at this shelter were at the top of their class but would never receive recognition for their hard work.

I was talking to a family that was three siblings and the one-month-old child of the oldest sibling. They asked me about my life and about the places I had been to. As I talked about having been to China and different parts of the US, I felt the discomfort of my circumstance falling over me. In my life, I have had the opportunity to leave my home and travel to various places for enjoyment, not for safety, while these people could not even leave the plot of land the shelter sat on. There were few economic opportunities in the area for the people of working age and many of the people expressed that they felt stuck with nothing to do.

I got to play with some kids and at the end, a girl wanted to play board games with me, but we had to leave. So that was it. They asked when we would come back and just like that, we left. This was just an afternoon on our 6-week long tour of the Borderlands.

I got to go back across the border that some have been waiting over a year to cross and may yet have to wait much longer. I will go back to our beautiful house in Tubac, and eventually return to the comfort of my home in Wisconsin and to my school in D.C., all while these people will still be there, still waiting, still hoping.

What do I do with that? They say that once we have seen the Borderlands, we will never forget it, but what do I do with everything I am learning?

A Life Left Behind

An artist named Tom Kiefer has taken what he has learned to a broader stage through art. In 2003, he was a janitor for US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and was disturbed as he saw food and personal items being thrown in the trash by CBP agents. He was struck not only by the amount of waste, but by the emotional wait behind many of the items left behind, whether bibles, rosaries, or photographs. Tom began collect some of these items over the course of several years. Eventually, after leaving CBP, he began to photograph some of the items, which began his photography collection, El Sueño Americano. This collection gives a glimpse into what some people coming into the United States leave behind.

CBP and BP Interactions

As Tom Kiefer demonstrated, CBP and Border Patrol have a significant presence in the border region. We were told that if you’re in the Sonoran Desert, chances are you are being watched. It could be by coyotes and travelers in the mountains, some of the beautiful birds and other fauna in the area, but more likely than not, you will be watched by Border Patrol.

So far, I have seen several of the Border Patrol’s white Ford F150s adorned with a green stripe and their slogan, Honor First. I have also now had two direct interactions with Border Patrol and Customs and Border Patrol Officers.

The first was near the San Miguel Gate, which is on the Tohono O’odham Nation. Our cohort we drove to see the gate with permission from the people whose lands we were on. There was no one around, but as we left and headed back towards the Sells District where we were staying, slowly Border Patrol trucks began filing in behind us, one by one until there were 5 trucks. Then they turned on their emergency lights and signaled for us to pull over. As we stopped, at least 10 border patrol agents came out of the vehicles. An officer came to the window informed us that we had just gone by the gate and turned around, he and some of the other officers inspected the vehicle and asked all of us about our citizenship status. Eventually, they walked away and let us go.

To us, it was very odd that it was necessary to have nearly a dozen officers there when we were in a vehicle clearly marked with our organization’s name. In many ways it seems that the mentality border patrol approaches the borderlands with is that they should see everyone as a potential threat, especially if they are people of color.

Later this week, after visiting Kino, our group walked back through the border checkpoint in Nogales. As I approached the CBP agent, I showed him my passport and was repeatedly questioned. First, he asked what I was doing, what organization I was with, what I bought, and where I am from. He then asked about the Packers (I am from Wisconsin), and if my state loves cheese. He keeps asking about BCA and what I am learning about the Borderlands, raising an eyebrow in suspicion. The interaction certainly felt like an interrogation as he was clearly trying to get me to crack or slip up. He told me I should be wearing a Packers hat instead of the one I had on. Finally, he asked me if I could pronounce my last name (for context, I have a very German-sounding last name, but am mixed race and do not look white). After successfully pronouncing my name for him, I was finally allowed to pass through to the US side.

Over the course of this interaction, three of my cohort mates had already gone through the checkpoint to the other side with another agent.

This was just one of the many times we will cross through the border during our time here. Yet, I think it’s important to think about the suspicion and questioning that came with this one interaction. There are thousands of people who cross through the border each day and all of them are treated to questioning. “Why should I let you into my country?” they seem to ask. “Prove to me that you are part of the group of people who deserve to be let in.” This constant rhetoric of suspicion reinforces the idea of us vs them. On the way into Mexico, all we do is put our bags through a security scanner, but returning to the US is coupled with accusation and suspicion.

It shows how the US treats its guests, and is just a glimpse into the system we have set up to keep people out of the country.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in

Such an important project, Aliyah. I can only imagine how difficult it must have been to 1) witness what you did, and 2) process it enough to write about it here. I hope you're taking care of yourself, and that you realize how brave you were to engage with this type of work.