LiA Reflection Week 3: Darkness and Hope in the Borderlands

This blog builds off of experiences from previous blogs. It may be helpful to read the previous ones: Week 1, Week 2, Week 2.5.

Preface

This is by far the most difficult week of my program, emotionally, mentally, and physically. Some of the experiences I will describe in this blog post will cover themes of sexual assault and death. These are experiences that were very difficult to go through, but that were important to understand on my journey to learn about the reality of the borderlands. Despite how difficult it is to experience, there are people who suffer through these experiences each day, and it is important to recognize the harmful things happening on the border that are too often ignored.

Dora’s Story

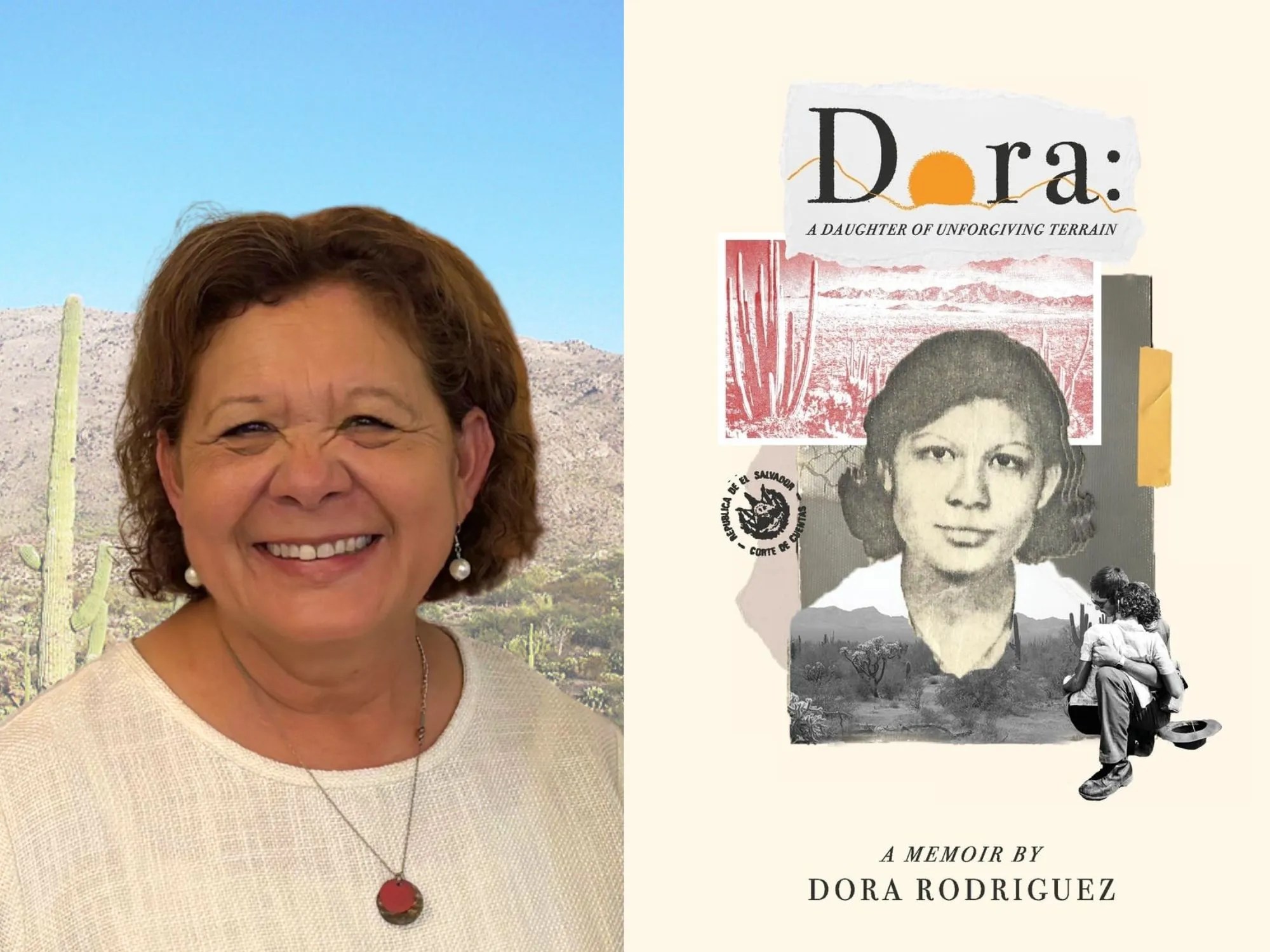

This week, we had the honor of sitting down with Dora Rodriguez just days before the official release of her memoir. She told us how she came to the United States from El Salvador in the 1980s, during the civil war. This civil war was funded by the United States and caused a tremendous wave of forced migration, where many had no choice but to leave their homes. She alluded to the horrors that she experienced in the desert. As I read her memoir the day I received it, I got just a glimpse of the devastation of her journey.

.jpg)

During the Salvadoran Civil War, she watched several of her friends and fellow activists die at the hands of the government. Dora knew that if she wanted to survive, she had to escape. She crossed the US-Mexico border and traveled through the desert in hopes of reaching safety with 25 others. When her group was found, only 13 of the 26 were still alive. She witnessed death and sexual assault of fellow travelers and so many other horrors through this journey. So many people believe that people who die in the desert deserve their fate for trying to cross into the country without paperwork. In this case and many others, the US contributed to the dangerous conditions and instability in El Salvador and provided no legal pathways for refugees to safely come to the US.

Dora is one of the most compassionate, brave, and caring people I have ever met. She now fights for asylum seekers in El Salvador through the organization she started with her kids, Salvavision. Her story is inspirational, and I highly recommend that everyone reads her memoir, Dora: A Daughter of Unforgiving Terrain.

She left us with a message directed at the youth of the world. She told us, “You aren’t just the future, you are the present. You are now, and you have to show up.”

The “End of the Wall”

We had the opportunity this weekend to take a trip to the “End of the Wall” with Tucson Samaritan, Gail Kocourek. I went into this experience with Dora’s story fresh in my mind. We drove along the hilly terrain the border wall is built upon, taking it in. We saw a mountain that was scheduled to be blown up to make room for the wall, several border patrol agents, wildlife, and took in the beauty of the landscape with the summer monsoon rains looming on the horizon.

Eventually, we reached the “End of the Wall,” where the wall simply ends. It is yet to be finished and is one of the many gaps that exists along the miles of Southern border wall. Last year, there was a camp for asylum seekers set up near this “End of the Wall.” Now, it appears that there is no one around. Gail told us that there have not been migrants spotted near the border wall in several weeks and that we likely will not see anyone.

As we start turning back, we see hands sticking out from the wall from the Mexico side and see three men dressed in camouflage. These were travelers preparing to make their journey across the border. I will likely never know their story or what happens to them.

As we left, I felt quite emotional as I thought about the horrors these men and their group might face. Not only will they have to cross through the unforgiving desert, but they will likely face many other barriers on their journey. I cannot help but overlay Dora’s story onto them, especially now that asylum seeking at the Southern border has ended.

If I had grown up in a different context or faced more difficult circumstances, maybe I would have felt forced to leave my home. Maybe I would look elsewhere for opportunities or do anything to support my family. They are people too, with dreams and hopes and aspirations. Why do some people’s lives matter more than others?

Alvaro’s Crosses

If you are ever in Southern Arizona, you may see painted wooden crosses along highways or in the desert. They are typically adorned with a rosary, and several stones.

Each of these crosses marks the spot where someone has died in the desert. Over 4000 human remains have been found on the US side of the border according to Humane Borders. Many estimate that the true number is far beyond that.

The treacherous terrain is deadly for the many who attempt to cross. Filled with mountains, cacti, and temperatures that fluctuate between blisteringly hot in the summer and punishingly cold in the winter.

There are crosses in the desert that mark the 13 individuals who died with Dora, and countless others.

Alvaro Enciso, a veteran and immigrant from Colombia, plants these crosses to honor the people who gave everything to better their lives. The project is called “Crosses: Where Dreams Die,” and allows Alvaro to honor the person who has passed. He makes each cross by hand and it was an honor to spend time with him, honoring the lives that have been lost.

It was striking to see the beautiful views and know that this may have been the last thing some individuals saw. It spoke to the constant dichotomy of beauty and hardships that we are learning about in the borderlands.

The Pima County Medical Examiner

Another thing we learned this week is that when human remains are found along the borderlands, from California to Texas, there is no uniform process for body identification or death investigation. It is either county-based or state-based, depending on which state, meaning a lot of documentation of the deaths in the desert is lost.

The Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office is regarded as one of the strongest offices in the country for “Management of Undocumented Border Crosser Remains.” We met with Gregory Hess, Pima County’s Chief Medical Examiner, who introduced us to his work. His office has worked with Humane Borders to create the migrant deaths map for Pima County and the Tucson Sector.

[Trigger warning: discussion of death and body decomposition]

This was a very graphic presentation. We were told and shown the processes of body decomposition in the desert. The pictures showed the devastation that the environment can do to human bodies, and their investigations revealed that many died due to blunt force injuries, firearms, or unknown causes (likely environmental, but body condition prevents certainty).

One of the goals of the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office, specifically, their anthropology team, is to identify bodies. Most of the migrants found are unidentified, and identification is difficult and time consuming, but they still make an effort to do so. They are rarely in a US fingerprint database, which means the office works with consulates and NGOs to try to identify bodies. Unfortunately, many of the bodies are in very poor condition, which makes fingerprint identification very difficult. Sometimes there are IDs, prayer cards, money, or phone numbers sewn into clothing, which can help, but may not be helpful if it is falsified or contain little identifying information. If possible, the office will try to get into contact with families who are either searching for missing loved ones or think their loved one might be found at the office. This can help them match tattoos or other identifiers with family descriptions. The office will try to do DNA identification when it can, but it is funded by grants and difficult to get coverage for it.

[End of trigger warning for death and body decomposition]

The Pima County Medical Examiner's Office’s work has been tremendously impactful in helping loved ones get closure. For many families who have been wondering what has happened to their child, sibling, niece, or nephew for years, they can finally know their fate rather than imagining the worst or living with the uncertainty of not knowing.

District Court

Another significant part of this week was spending time in hearings both at District and Immigration Court. The District Court is for criminal proceedings while Immigration Court is for immigration hearings.

In District Court, we watched as several men were brought into the courtroom in orange jumpsuits and five-point shackles. They shuffled in, chains dragging on the ground, and many struggled to raise the headphones used for translation up to their ears. What were these dangerous crimes that they were accused of? What had they done that meant they needed to have chains immobilizing them from their wrists to their ankles? As the judge said, their crime was a “petty charge of illegal entry.”

The judge quickly went down the line of men, giving their sentences, and once the proceedings began, they were out in a matter of minutes. We were told this rapid-fire sentencing is actually better than it has been in previous years, when, instead of 7-12 individuals, there were dozens being rapidly sentenced. This felt inhumane in many ways. The judge spoke to us afterwards and stated that he tried to given the defendants as much respect as possible, and to move it forward so it does not drag out these proceedings. He urged us to act and to change the policies because he felt that, as a judge, his only power was to enforce existing ones. In many ways, I could understand his sentiments. These were policies that set up dehumanizing treatment. Policies of optics that dictated how people were treated, that dictated that people who cross a border without papers should be treated as the world’s greatest and most dangerous criminals. It made me think about whether many of these crimes on the records of migrants in this country are simply illegal entry charges.

Throughout the day, we went to various court rooms, seeing many different cases. Several were charges based on entry to the US, while others were related to drug cases. We saw how phenomenal the provided translators were, but also how harsh the justice system is on people who are the most desperate. We also heard that several of the attorneys defending these individuals had not been paid yet this year due to Congress withholding funds.

The cases we saw, where some were convicted to ensure precedents were set, where some were told to plead guilty so they could build evidence against the wider networks, and where judges came up to us questioning whether they should have given the person they just sentenced a lesser sentence, are the realities of our court system. I couldn’t help but feel that these court rooms were places that tore families apart, and where no person left the room happy.

Immigration Court

The next day, we went to Immigration Court, where we sat in on an asylum application hearing. The man in the hearing had entered the country under Temporary Protected Status (TPS) from Venezuela. This status was in the process of being revoked by the Trump Administration, so he was applying for asylum. To be clear, the conditions in Venezuela have not changed since Trump took office, just the US policy on this status.

We sat through two and a half hours of a devastating hearing, although we knew the outcome of in the first 30 minutes.

One of the first things we realized was that since this was a civil proceeding and not a criminal proceeding, the defendant did not have the right to representation. Additionally, the translation services were not held to as high a degree as those in the criminal courts were. This gentleman’s translator was connecting via Zoom and cut out several times during the hearing, frustrating the judge and leaving him with no one to explain what was happening with his situation.

While this gentleman had no representation, the Department of Homeland Security sent two prosecutors to this hearing. As I sat behind them and watched them send texts and type away on their computer, I couldn’t help but think about how much those two were being paid (in taxpayer dollars) to sit there and take away someone’s hope for a better life.

The defendant gave us his permission to stay in the room, which I was selfishly grateful for, as I would have the opportunity to hear his perspective, but I was also heartbroken about it. We were simply listeners as he vulnerably revealed the entire story of why and how he came to be in this country.

For the sake of his privacy, I will only briefly describe what he discussed. He told the judge that due to lack of healthcare access, his family had suffered several tragedies. Also, due to lack of economic opportunity, he did not have a way to support his family. Additionally, he had gone blind in one eye, which made it difficult to find employment. He came to the US through the TPS program in hopes of being able to work and support himself and his family so they would not again go through such hardship.

Throughout this process, he faced ruthless and patronizing questioning from the judge. When he would occasionally answer her questions with “okay,” rather “yes” or “no,” she would stop her questioning to correct him, often slowly and pointedly stating, “No. Not okay. Yes or No,” and waiting for the translator to pass on the message. She would also interject with a sharp, “Listen,” if she did not feel that he had answered her question properly, before slowly repeating the question. The judge’s frustration was clearly heightened by the intermittent dropping out of the translator. However, the patronizing way that she conducted her questioning made all of the listeners in that room feel uncomfortable as we watched a grown man, a father with adult kids, get treated like a child.

Given how high we knew the bar for asylum was going in, it became clear pretty quickly that he would not be eligible. Under US policy, having dire economic conditions is not a good enough reason to deserve to stay in this country. Even when the judge asked the gentleman whether he had more to add to his reasoning, he said that he had to be honest and could not say something that had not happened.

When the final verdict was read, he was told that he would be subject to deportation unless he appealed the verdict, meaning that he may have to return to the difficult conditions he was facing in Venezuela. He had faced a harrowing journey from Venezuela to the United States, and now that might all be undone.

I am certain many similar hearings are happening around the country each day. I will likely never know this man’s fate either. As this has been just one more week in our time in the borderlands, leaving me with the question:

What do I do now with all that I have witnessed and experienced?

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in