Kashmir, The Home Out of Reach? - LiA Week 5

So far, my work has unfolded in stages. Week 1 was devoted to preparation: planning research trajectories and connecting with professionals whose expertise could guide me forward. In Weeks 2 and 3, I turned inward, building intellectual and methodological grounding: reading memoirs and academic analyses, listening closely to existing oral histories, attending a conference on oral history, and initiating contact with community leaders whose trust is indispensable in this work. By Week 4, I transitioned from preparation to practice, conducting my first interviews with individuals who had lived, or still live, in the migrant camps of Jammu.

In Week 5, my research took an unexpected turn. Although I had decided against visiting Kashmir earlier in the year due to the war, reports of relative stability encouraged me to go. I knew it carried risks, but I also felt that without hearing directly from those still in the Valley, or those who had returned under the rehabilitation scheme, my work would lack a crucial dimension. Their presence, their silences, and their daily negotiations with fear and belonging were essential to understanding the fuller landscape of Kashmiri Pandit life.

The city met me with quiet stillness: no tourists on the streets, the Dal Lake subdued, and Kashmiri the only language cradled in the air. It was, suddenly, home. The next morning, for the first time in my life, I went to South Kashmir and began conversations with those who had either remained in the Valley since 1990 or returned under the government rehabilitation package.

These accounts revealed both the persistence of loss and the ongoing climate of fear. For one man recalled a night in 2001, nearly a decade after the exodus, gunmen barged into his home during dinner, shooting indiscriminately, killing his father and younger sister before his eyes. She was six and he was eleven. Another person, after agreeing to speak with me, refused altogether to engage with questions about the exodus. His silence was not an absence but a presence, a reminder of how fear continues to shape expression and existence even 35 years later.

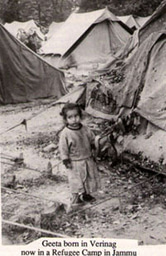

Separation stood out as one of the most enduring sources of pain. Not only from their home, land, and way of life, but from their family. Families that once shared generations under a single roof have been scattered across states, countries, and continents with no real path to return to home. One man told me that while he still lives in Kashmir, his parents, wife, and daughter remain in Jammu. Their “resettlement” under the government’s scheme has confined them to cramped housing: six families in one small apartment, two families to a single room. The room itself is no larger than my dorm in New York, far too small for a family to live with dignity. On top of this, the constant security anxieties, the fear that an attack could come without warning, make even the most basic rhythms of family life feel fragile. The result is often forced separation: one parent and children left behind, visits reduced to phone or video calls. When I spoke with his daughter over a video call, she beamed with a bright confidence, her excitement clear as she shared her achievements playing on the state cricket team. Yet when she, a middle school girl, described going weeks without her father, her voice wavered, a reminder that distance, confinement, and fear etch deep marks no technology can erase.

The physical environment of the settlement is itself central to the story. Many residents call these apartments “prisons,” their gates locked and guarded. The restrictions are not arbitrary. They are a direct response to the many attacks and killings carried out against Kashmiri Pandits who chose to return to their homeland in the last 20 years. Locked gates are meant as a shield against that violence, but they also turn daily life into waiting: movement curtailed, safety purchased at the cost of freedom. For many, this bargain is not a matter of choice but of endurance, a way to survive in a homeland that still refuses to welcome them back without conditions.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in

This was a very moving narrative. Thank you for sharing!