What We Owe the Past - LiA Week 1

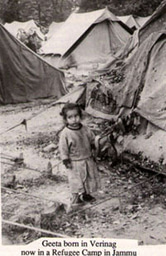

The main reason I’m doing this project comes down to one line that has stayed with me ever since I heard it in an interview during my research last year: “Truth must precede reconciliation.” It struck me then, and it keeps echoing now. Especially in contexts like Kashmir, where retributive justice is nearly impossible, truth becomes not just important, but essential as it is the only place to begin.

I thought I’d spend this summer mostly listening to voices, memories, and stories that have been buried under fear and systemic neglect for decades. Stories that were pushed aside by trauma, time and the effort of survival to the point of being forgotten. I imagined sitting across from people and hearing fragments of a past they had carried alone for too long. But before I could ask anyone to share their truth, I had to ask myself: What does it mean to be entrusted with someone’s story? How do I protect it? How do I share it responsibly?

In the past week, I’ve been working through the practical side of setting up the project: reviewing consent form language, checking ethical review protocols, reading through archiving standards, and figuring out how to responsibly store and share interviews. I’ve reached out to several archives to better understand their submission processes, narrator rights policies, and storage conditions. I’ve also been learning about how to make sure narrators retain control over their stories long after the interviews are recorded.

The responses I received were all extremely gracious. People were kind and generous with their time and resources. They shared thoughtful insights, pointed me to useful tools and readings, and offered support well beyond what I expected.

Outside of those conversations, I’ve also been:

- Drafting layered consent forms that give narrators flexibility in how their stories are used and shared.

- Researching data storage options that are both secure and accessible to the community.

- Talking to professors, archivists, and historians from institutions across the world, some of whom have taken me under their wing, for which I’m grateful.

- Getting the community involved and making sure they have a say in how this work takes shape so that the project reflects their needs and I can better understand the range of perspectives and grow in the process.

- Reading books (with the Oral History Toolkit series being an amazing introduction to the field), attending webinars, and keeping up with articles and recent conversations in the discipline.

This experience has reminded me that oral history is about how we hold stories (and hence history), how we earn people’s trust, and how we stay accountable long after the interviews end.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in

This sounds like a truly enlightening experience! I really appreciate how you emphasize the importance of an interviewee's autonomy before, during, and especially after!

Thank you, Tara!!!