Characterizing Post-Diagnosis Gaps Along the TB Care Cascade

Background

Tuberculosis is the world’s leading infectious cause of death, and India has an especially high burden of both incident cases and death when compared to the rest of the world (World Health Organization, 2023). The World Health Organization (WHO), which regularly sets goals for countries in reducing the prevalence of infectious diseases, suggests that India has many missing patients, or patients who are not within the national system and, therefore, may not be receiving adequate care. In India, TB is ideally treated through government centers, which have a specific testing and treatment protocol based on WHO standards. There is, however, a private sector that people often go to, which includes doctors with an MBBS (western medicine) and folk medicine providers. People who go through the private sector or are not treated are considered “missing” because there is no way to ensure that they are receiving the correction medication or taking it for the appropriate amount of time (Satyanarayana et. al., 2011; Hazarika, 2011). The national system was developed in 1997, combining the many national and regional programs that developed post-independence. The program sought to reduce the very high prevalence of tuberculosis in India with a more public health approach, and it was called the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) (Verma et. al., 2013). This involved creating treatment clinics across India’s regions where people could get tested and get treatments. The national system was formulated under the Direct Observation of Treatment model as created by WHO (World Health Organization, 1999), and has since gone through changes to expand access to care. Recently, to reflect the WHO and Indian goal to totally eradicate TB, the program was renamed to the National TB Elimination Program (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, 2018).

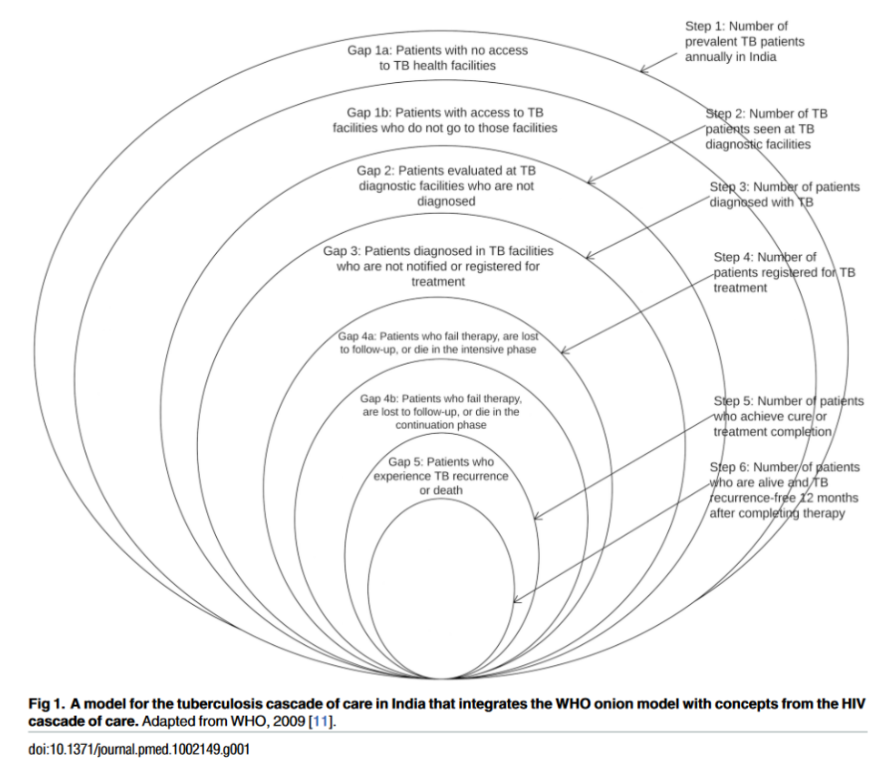

Even for patients who are able to participate in existing national infrastructure for tuberculosis treatment, most people are not cured. There are several points of “drop-off” in care, including people who never make it to a clinic, are diagnosed incorrectly, or are unable to finish treatment. This is all outlined in a framework called the Tuberculosis Care Cascade, which highlights specific milestones a patient should be reaching to be cured. The cascade was developed during the transition from TB reduction to eradication to broaden the government system from just having treatment available to target problem areas across the course of treatment to create a sustainable model on both the individual and broader scale (Subbaraman et. al., 2016). This model is a combination of the onion model proposed by the WHO for tracking TB care on the national scale and the “continuum of care” model used for HIV treatment, altered slightly because active TB is not a lifelong condition (World Health Organization, 2009).

Figure 1. TB Care Cascade (Subbaraman et. al., 2016)

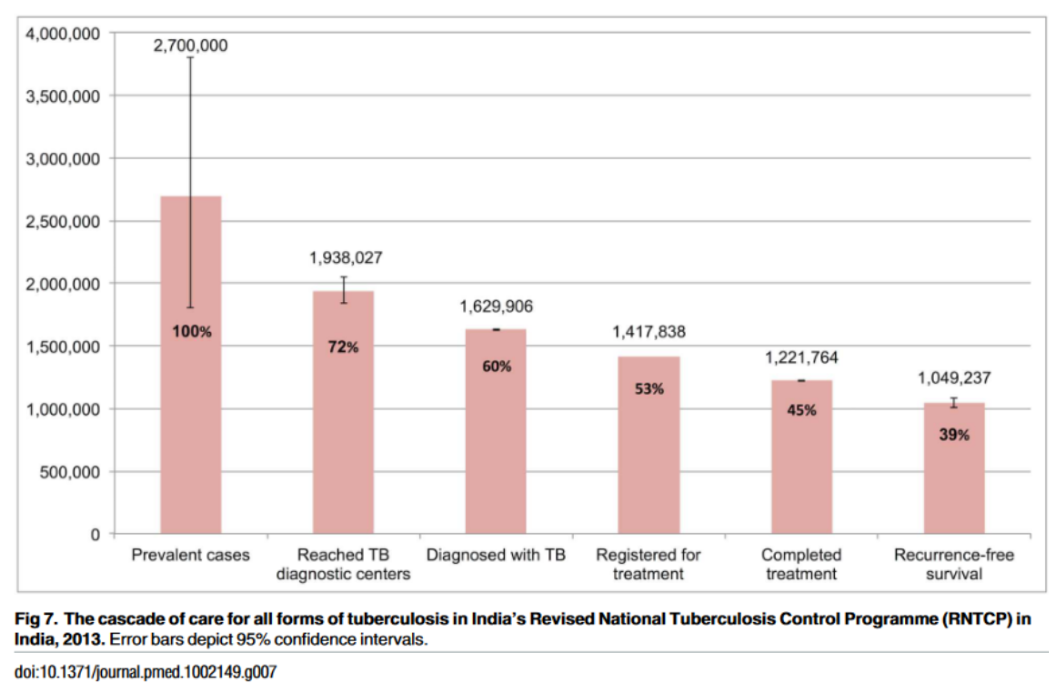

Data from the national TB treatment system is being used to “fill out” the cascade and analyze which points need the most fortification. Previous studies have found that the biggest gap in care is the one between prevalent cases and getting to a government TB center for evaluation. However, it is important to first fortify the system before recruiting new patients so that they are more likely to reach recurrence-free survival. Furthermore, these efforts will ensure that people already within the system are able to finish treatment so they do not develop multidrug resistant TB and cannot pass the condition to more people. The study discussed here is part of a larger cohort study following patients from diagnosis to survival; specifically, this study looks at patients who “dropped off” from the cascade after diagnosis, during treatment, or experienced recurrence.

Figure 2. The Cascade of Care in India’s RNTCP, 2013 (Subbaraman et. al., 2016)

Methods

To better understand how the system is able to attract and retain patients, the Finding and Retaining India’s tuberculosis patients study (TB STAMP) enrolled participants as they were diagnosed to follow their progression along the cascade. This study focuses specifically on people in Gaps 3, 4a&b, and 5 (labeled A, B, and C in this study), which is those who start but do not finish treatment or those who finished a full course but contracted TB again (called recurrence) or passed away. Many people who start treatment never finish it, either because they pass away or some other factor (or factors) stops them from being able to get and take treatment. The overarching goal of this research is to deeply examine these three gaps and understand what differences and similarities exist between each gap. By investigating the reasons causing people to fall into these gaps, we hope to understand the structural or systemic barriers to care and whether they remain constant as we progress along the cascade. To understand exactly what these factors are, we are looking to see how patients interact with the healthcare system, which circumstances surrounding their life may have made it more difficult to get care, and how general perception of the disease affects both patients and healthcare workers. At the end of this study, we hope to have the information needed to fortify the TB care system to both retain existing patients and to ensure new patients are able to make it all the way down the cascade

This study started in India, where the research team used patient records that microscopy centers collected to follow up with them based on their treatment outcome. Interviewees and their families were asked questions about the course of their treatment and what was going on when they stopped, with probes incorporated into questions to help patients identify what problems they may have been experiencing. These questions were based on the stage at which the patient stopped treatment and whether the interview was with the patient and/or family members. Questions included those about challenges in starting/continuing treatment, including navigation/transportation, lack of information/guidance on medicine, discrimination, availability of medicine and healthcare professionals, medication side effects, food availability, work constraints; challenges in daily life, including illness symptoms and/or side effects, work or other responsibilities, lack of money and/or food; and personal challenges, including stigma from family/friends, lack of social support, and family events/holidays/festivals. If family members were present, similar questions were asked about their experiences in supporting the person with TB and challenges the family may have been facing.

Currently, we are working on translating all the data from Hindi to English. As the interviews are being translated, we are also working on coding them with themes that people experience. This can range from broader societal issues, such as stigma or cultural norms to specific issues with the healthcare system, such as unclear communication of diagnosis. Once the interviews are coded, they will be statistically analyzed to find the most common issues and then used to target specific parts of the care cascade or TB care infrastructure that can be used to improve outcomes.

After each interview was translated, two coders went through and tagged important excerpts that demonstrated one or several of the previously agreed upon codes, which represent common barriers to care. The interviews are blindly double coded, meaning neither coder sees what the other one has marked until after both codes are done. After both coders went through and coded each file, they compared their results and reconciled the codes into one master account. After reconciliation, the Dedoose analysis feature (Dedoose Version 9.0.17, 2021) and Excel analytical tools (Microsoft Excel, 2018) were used to find which codes were used more often in each gap, extract excerpts from each code based on the gap, and read through excerpts to identify themes and overlaps.

Results

While official results are not yet known, there are some preliminary observations and trends. (As a note, thus far, the majority of observations are based on gap B, which is treatment drop-off. There are some insights into gap A, which is pretreatment LTFU, but most of Gap C has yet to be analyzed and coded.) These are the most common issues reported in Gap B:

COVID 19 was a major hindrance for many of these families across all gaps, but especially in Gap B. With hospital beds being filled up or facilities being shut down, it was very difficult to find a location in which patients could receive care. There were also many curfews and legal restraints under place that stopped people from leaving their homes. Many people specifically said that they were turned away or told that TB treatment was not ongoing during lockdowns, which certainly hindered treatment.

“We got him shown to a few people. At first he was able to get some rest, then after that, he didn’t get it. Then lockdown was put into place. Then he wasn’t able to go and we had to get new records. They gave us medicine once and then never gave it again. How long are we supposed to do this?”

This shows how lockdown not only temporarily stopped people from their ongoing treatment, but also caused a lot of disruption within the health system that meant they had to start the rather tedious process of registration and prescription over again.

Additionally, the treatment regimen for TB is at least 6 months long, and several families mentioned concerns about the medicine being too warm for their body. In Indian culture, most things you eat are considered either warm or cool to your body, and having too much of either one will send your body into an imbalance and cause even more medical issues (Pool, 1987). Medicine of any kind is considered warm unless it is specifically meant for cooling. This was especially common in patients who switched between different facilities or had recurrence, so concentrated in Gaps B and C, because they usually took the medicine multiple times. Side effects were a major concern especially for those in Gap B, which were those who started treatment but stopped midway through. Many of them cited symptoms such as dizziness, restlessness, and anxiety, which they interpreted as the medicine being bad for them and then stopped it. The concern of side effects was most commonly noted along with a lack of hunger and a lack of symptom improvement. The following quote demonstrates the concerns many families had with the medicine:

Interviewee: Yes, my urine was red. (Unclear exactly what he’s saying, but I think something about his skin being yellow). And I definitely felt warm.

Interviewer: I see. You felt very hot?

Interviewee: No, it was warm to the body.

Particularly for patients in Gap B, there were significant negative interactions with healthcare workers that may have made patients nervous to ask questions or clarifications or even return to the same health facility. As an example:

Other man: We are going crazy, it isn’t working here nor there. (pause) They say, “Oh, you didn’t give her medicine, why didn’t you…”

Other woman: We were giving her medicine well!

Other man: They said we were hanging around on trees and that we were being negligent.

The negative interactions were often coded along with Covid, which is somewhat understandable as staff was rather stressed at the time. However, these interactions point to a larger, systems-wide problem of exhaustion and understaffing that is ultimately leading to TB treatment dropoff.

Implications

While it is unclear what exactly the final results will be and how they may all relate to future recommendations, there are some general trends that can already be seen as well as indications for where future research may help. Perhaps the most prevalent trend in all of these interviews was Covid-19; even if patients did not cite the pandemic as the reason they stopped their medication, almost everyone mentioned its impact in some form. Covid-19 revealed weaknesses in healthcare systems around the world; while Covid-related issues such as lockdowns are not something to be “solved,” what can be done is fortifying the healthcare system to be able to provide continuous care, even during times of struggle. Issues most commonly reported in relation to covid were a lack of facility/staff, drug shortages, lack of other supplies, or facility closures. While Covid is unlikely to make a comeback at the same scale as when it originally started, other outbreaks or natural disasters may cause similar disruptions, especially as the effects of climate change get stronger. These certainly are not easy fixes, but require intense fortification of healthcare systems. This includes stronger supply chains for TB medications, designated locations and staff for non-outbreak treatment or antibiotic pick-up, and strong record keeping and follow-up with patients who have not picked up medication to see if the emergency situation has hindered access.

Furthermore, thorough patient education seems to be insufficient, specifically with what side effects to expect and when relief will be felt. While many patients seemed to have a strong grasp on when + how to take the medication, many of them were surprised at the side effects.

Noticing red urine, for example, made patients very concerned about their body’s internal balance - however, this is normal and indicates that the drug is having its intended effects. Patients also experienced a lack of hunger and dizziness, the latter of which is not a known side effect but is certainly something that people cited as a reason why they stopped treatment. This side effect caused many to not be able to work, which is why they had to stop treatment. Many of them also mentioned that they did not visit a doctor to see if the side effects were of concern (it seemed as though they were never told or never considered going to the doctor). These side effects led many to believe that the medicine was too “warm” for them and ultimately contributed to incomplete treatment. To improve compliance, it would be helpful to teach patients what the expected side effects are, so they are less alarmed at them, and emphasize that patients should visit a doctor if they are struggling with side effects before stopping medicine. Having doctors provide information about the heat of the medicine might also be helpful (not saying that the experience is wrong, but explaining the importance of the medicine and suggesting ways to cope), as many people seemed to have concerns about this. Further research should also investigate the claims of dizziness, as it is not an official side effect from the given treatment to see if it is a manifestation of a different side effect or entirely different issue.

Lastly, many of the issues that patients face are in interacting with the system (a lack of knowledge, confusion, refusal of care) - while it can be easy to blame individual healthcare providers, a lot of these issues are likely due to system-wide inefficiencies causing employees to be overworked and stressed. Along with interviewing patients, the parent cohort study also involved interviews with healthcare workers to understand the issues they face. This will allow for a better understanding of how the TB treatment system works across the several month period and what large-scale changes will help both employees and patients engage in this process.

Conclusion

Though analysis is not entirely complete, it is clear that getting patients through the cascade to one-year, recurrence free survival relies on fortifying the systems that people interact with. This includes ensuring a constant supply of medicine, adjusting education to help patients cope with effects of medicine, and improving accessibility through increasing staff and keeping more facilities open. Like stated earlier, further research into the issues that healthcare workers are facing might reveal why it is difficult for patients to navigate the health system or facilities are unable to consistently provide care. Thinking large scale, solving issues of system vulnerability and fortification requires further investment into the government infrastructure of TB. Across all these interviews, people generally wanted to get better and went to great lengths to do so. By investing into the systems that these patients engage in, we not only ensure that they can be cured of their TB, but also prevent its spread.

References

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. (2018). India announces plan to end tuberculosis by 2025. Retrieved from https://www.gatesfoundation.org/ideas/articles/india-announces-plan-to-end-tuberculosis-by-2025.

Dedoose Version 9.0.17, cloud application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data (2021). Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC www.dedoose.com.

Hazarika, I. (2011) Role of private sector in providing tuberculosis care: Evidence from a population-based survey in India. JGlob Infect Dis, 3(1), 19–24. doi: 10.4103/0974-777

Maher, D., & Mikulencak, M. (1999). What is DOTS? World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/65979/WHO_CDS_CPC_TB_99.270.pdf;jsesiolto.

Microsoft Corporation. (2018). Microsoft Excel. Retrieved from

https://office.microsoft.com/excel

Pool, R. (1987). Hot and cold as an explanatory model: The example of Bharuch district in Gujarat, India. Social Science & Medicine, 25(4), 389–399.

Satyanarayana S., Nair S.A., Chadha S.S., Shivashankar R., Sharma G., Yadav S, et.al. (2011) Where are tuberculosis patients accessing treatment in India? Results from a cross-sectional community based survey of 30 districts. PLoS ONE, 6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024160. Subbaraman, R., Nathavitharana, R. R., Satyanarayana, S., Pai, M., Thomas, B. E., Chadha, V. K., Rade, K., Swaminathan, S., & Mayer, K. H. (2016). The Tuberculosis Cascade of Care in India's Public Sector: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PLoS medicine, 13(10), e1002149. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002149.

Verma, R., Khanna, P., & Mehta, B. (2013). Revised national tuberculosis control program in India: The need to strengthen. International journal of preventive medicine, 4(1), 1–5.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care, and control after 2015. Geneva: WHO, 2013 Contract No.: EB134/12

World Health Organization (WHO). (2023, March 4). Tuberculosis (TB). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in