There was not a better way to conclude our work with partner organisations than with Forest Post. Week five of CraftHER we travelled to Athirapally to spend time with the incredible founder of Forest Post Dr Manju Vasudevan and some of the women forest-dwellers who made the journey from the forest to meet us. Manju spent the first years of her career researching canopy pollinators. She worked with organisations such as ATREE, Foundation For Ecological Security or FES and the Keystone Foundation. She subsequently completed a PHD in Pollination Ecology at Imperial College London. She was Fulbright Nehru postdoctoral Fellow at the University of California in 2014 and now consults with grassroots NGOs and conservation groups across Kerala as one of the Duleep Matthai Nature Conservation Fellows. Manju’s work on

Forest Post began as a project in 2017 supported by the Keystone Foundation - a foundation that works with indigenous communities on agriculture, food security, land and community rights, community health, development and conservation of biodiversity. The project started in the Nilgiris as part of the activities of a grassroots network under the Global Alliance for Gender and Green Action (GAGGA). After working as an NGO for three years, in 2020 there arose the need for a business model. This support came from the UNDP-India (United Nations Development Programme).

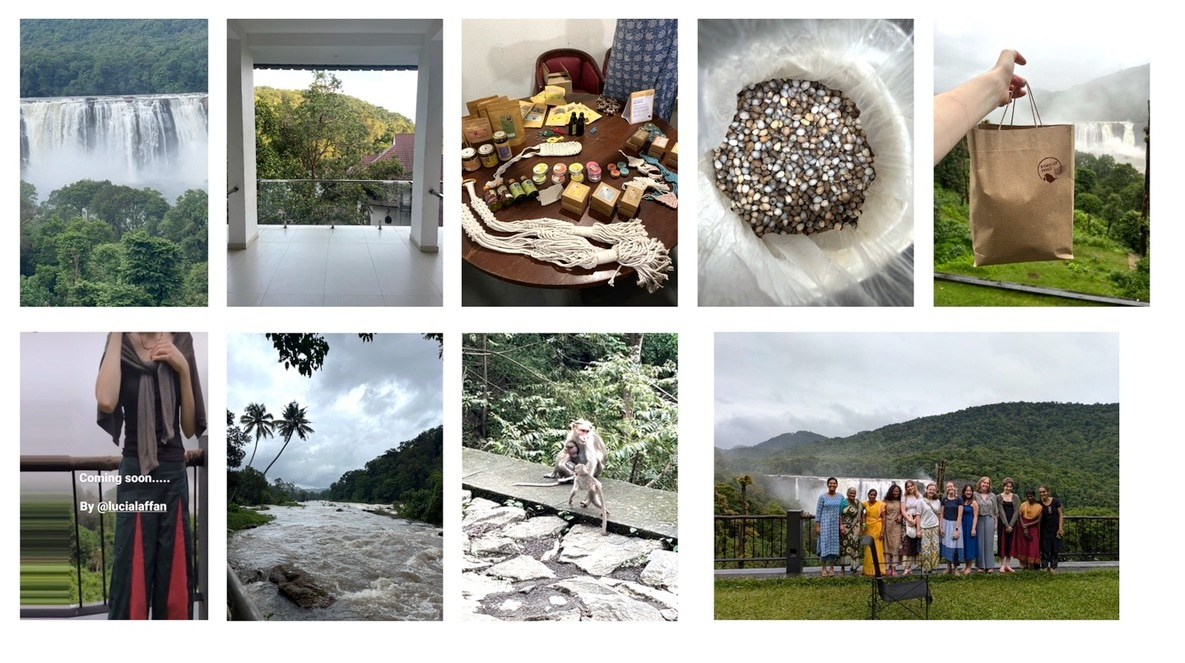

Forest Post works with women’s enterprises across eight villages in Chalakudy, Periyar and Karuvannur River Basins in central Kerala’s Western Ghats. These women work in the production of beeswax skin care, bamboo and macrame craft and also wild foods. The raw materials that make Forest Post products come from seasonal harvests and these groups of women are so familiar with the forest geographies and landscape variations that nothing is wasted. I believe a big message that Manju wished CraftHER take away from our interactions is the true meaning of “sustainability” as located with the seasonally directed work of these forest dwellers. Manju’s argument for Forest Post’s intervention is that the security of the livelihoods of these native forest-dwelling communities is inextricably tied to the security of forest conservation. In a world increasingly threatened by the pending risk of climate collapse this seems more pressing an issue than ever. These communities continue to engage with the forest and its resources for both sustenance and sales but in doing so they simultaneously preserve knowledge of the forest and keep watch over its distribution. Forest Post describe these communities as “Stewards of Conservation”. The purpose of Forest Post then is to find creative and dignified sources of income by consequential engagement with the forest land. With this structure in place these people are not forced to migrate to towns in search of other work or income.

Typical sources of income for these communities such as honey or medicinal plants are bought by the Forest Development Agency of the State Forest Department at fair prices. However, with inevitable market fluctuations, uncertainty of income plague this system of sale for the people of Adivasis. Forest Post helped bring more forest resources such as wild grape or asparagus into the harvest regimes of these communities in order to stimulate fairer prices. In addition, Bamboo weavers were provided with training on design and treatment of the wild resource. Skill development can and does now (thanks to Forest Post) enhance forest produce to support the local economy. In addition to this Forest Post’s training addresses gender equality issues by building the confidence of the women production groups.

The day with Forest Post was spent at the beautiful Rainforest Resort against a dreamy waterfall backdrop. The women arrived around 11am after rising at 3am, making breakfast, lunch and completing household chores for their families prior to a 6km trek across the forest to the nearest town to catch a two hour bus (the first of which they missed). They demonstrated their weaving skills as we all sat in a circle on the floor. We asked questions and Manju translated. Then we went for lunch. The women speak their own tribal dialect but they also communicate in Malayalam. What I found most interesting about our meeting was their difficulty in understanding the phraseology of our questioning. It became clear that we were phrasing all our questions in our own distinct temporal perhaps “capitalistic” frame. For these women, they do not share the concept of time to be “spent”. They are task and seasonally oriented. Time is less something to be spent like a currency. In fact these women did not know their dates of birth or their own age. Time is something that is dictated by nature and season, this lack of concern for something so principle to all capitalist framing seemed refreshing and perhaps highlighted a better or even a necessary way to practice sustainable living.

I cannot express my gratitude to CraftHER Project Coordinator Preetha Matthews enough for introducing the group to Manju and this incredible business. After the women’s return to the forest we had tea with Manju where she told us more about the business and her brilliant plans for its future. We then of course made obligatory completely guilt-free purchases of Forest Post’s incredible array of products. An incredible completion of CraftHER week five as we return to Kochi for our final week!

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in

I'm so glad you enjoyed the experience. It was wonderful to see you engagewith the women with such an open mind andwillingness to learn, Lucia.

I found itfascinating how these communities view "time"—following natural cyclesinstead of thecapitalist idea of time as money. This approach challenges ourusual way of thinking and shows a more balanced way ofliving with nature.

What other aspects of their way of life did you find inspiring?