Turns Out, Installing CUDA Isn't Hardest Part of Leadership

In this blog post I go over my Leadership-in-Action experience at Ersilia. Ersilia was the first organisation I came across when I was exploring options for my LiA experience, and they immediately clicked with the my vision for this. I am incredibly lucky and grateful that my first (and only) choice got back to me and were more than willing to take me on. Ersilia has an absolutely incredible and inspiring mission: Accelerating sustainable research and drug discovery to fight infectious diseases and promote scientific activity in the Global South.

The Ersilia team is small yet brilliant and very high-performing. All of them are post-PhD in computational biology or chemistry — I came in a with software background. I had to learn how to communicate clearly across disciplines, ask the right questions, and more importantly, listen when the answers challenged my assumptions.

Before I go into what I did at Ersilia, I want to briefly introduce something that was at the core of my project at Ersilia: Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), specialised processors/chips designed to handle thousands (maybe even millions, billions?) of tasks at once, in parallel. Perfect for powering everything from rendering video games to AI models. We are in an era of unprecedented AI adoption, and the advent of increasingly better GPUs can be credited largely for this (Nvidia’s volcanic growth is clear testament to this).

Ersilia’s platform hosts a library of machine learning models (primarily in their flagship project The Ersilia Model Hub) for researchers working in low-resource environments. The catch? Most of the models were running on CPUs, which meant some models suffered from limited performance, and whole classes of models, such as transformers, were just plain impractical. The goal of my project was to Incorporate GPU Acceleration Support in the Ersilia Model Hub:

- Prove that GPU acceleration could work with Ersilia’s current model stack

- Benchmark performance improvements (compared to CPUs)

- Create a framework that allows easy integration of GPU support into future models and hopefully retrofit existing models

Basically, I had to build something useful, sustainable, and robust: ideally without breaking anything else in the process.

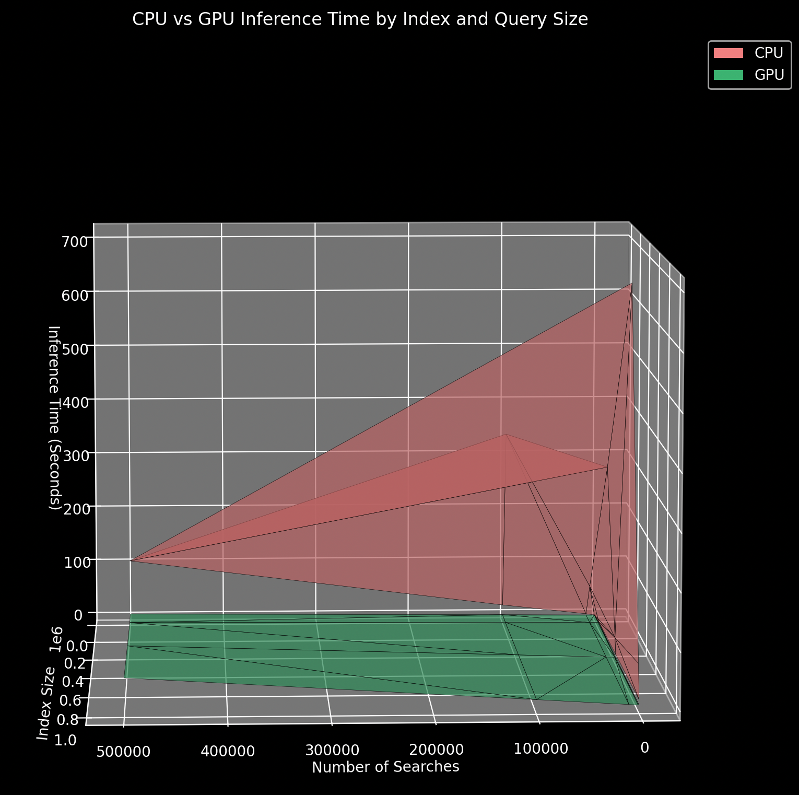

This involved building a full proof-of-concept for GPU-accelerated models using Docker and CUDA (Nvidia’s parallel computing platform that lets GPUs do the heavy lifting for tasks like AI, by running batches of operations at once instead of one at a time), starting with a few representative models to test performance and compatibility. I ran performance benchmarks comparing CPU vs GPU execution across various models, helping to quantify speed-ups and highlight which models would benefit most from acceleration. This work not only laid the foundation for more powerful models to be integrated into the Ersilia Model Hub, but also ensured that future contributions could easily build on the GPU-enabled framework.

Fig: A graph from my preliminary experiments showing GPU Speed-ups

You might be wondering, where does leadership come into action here?

I thought this project would be mostly technical. What I learned very quickly is that technical leadership isn’t just about writing code. It’s about:

- Communicating ideas to people with different backgrounds

- Making trade-offs when “ideal” solutions don’t work in real-world environments

- Designing for constraints that aren’t your own

And most importantly: realising when you don’t know something, being okay with that; and asking for help. I have a habit of trying to solve problems in isolation. This summer showed me how counterproductive that can be, especially when working on mission-driven teams. Asking for help isn’t a weakness; it’s an accelerant (pun fully intended).

Working with an organisation focused on the Global South forced me to confront some uncomfortable truths. I had to unlearn my default assumption that “newer is better” or “more powerful = more useful.” Sometimes, designing for impact means scaling down, not up.

There’s a real ethical dimension to tech-for-good work. Who are you building for? What assumptions are you making? And most importantly: Will the people you’re trying to help actually be able to use what you build? These questions stayed with me, and they’ll shape how I approach leadership and innovation moving forward.

This Leadership-in-Action experience was not just about trying to add GPU support to the Model Hub, although that did happen (somewhat). It was about growing into the kind of leader who can operate in uncertainty, centre impact over ego, and collaborate across disciplines, cultures, and constraints.

To Past, Present and Future Scholars/Leaders (or anyone reading this really):

Whatever you're working on, whether it’s GPUs, economics, history, or public health, take this as your reminder: Leadership isn’t a title or a fixed skillset. It’s a mindset. One that you develop, one awkward team call, revised plan, and small breakthrough at a time.

And yes, sometimes it involves installing CUDA.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in