Some Thoughts After 6 Weeks in Uganda (LiA reflection essay)

Two years spent as a medical student and I’m knee-deep into the vast art of understanding the body. Yet, my most significant learning is that medicine loses its worth if it does not reach the people it intends to serve and, unfortunately, this is the case for many people in both developed and developing countries. Knowing this, I became curious to understand the causes of insufficient healthcare access in certain communities and what can be done to improve it. My interest in matters of global health was what drew me to join the Kibale Forest Schools Program (KFSP).

Of course, my main aim with this trip had always been to work with KFSP on their sustainable health-related projects. This work aimed at improving the public health of the communities surrounding Kibale National Forest at multiple levels from prevention to treatment. As it was intended as a ‘Leadership in Action’ project, I was privileged to have developed and learnt so much about my own leadership. However, most my learning stemmed from the opportunity I had to learn so much of the culture and systems in place in this community to not only incorporate into my work with KFSP, but to inform me further on my hopes to understand and help similar communities through work in the field of global health. In retrospect, I realise that through these learnings themselves were important underlying themes of leadership, which I will also be sharing in this essay.

The health team was assigned 2 main projects. The first of which focuses on Village Health Teams (VHT), which is a system that was recently put in place to tackle the lack of healthcare access in remote and rural villages by setting up a team of locals living in the community itself to act as the first point of call for health-related problems. Unfortunately, what began as a great idea was poorly executed. The team of locals acting as the VHT were often only educated to the primary level and were not given any resources or training to guide them in their duties. This project aims to write and publish a VHT Training Manual and Training plan to provide VHTs with these resources that they have expressed a wish to have.

While in Uganda, I found that the community views the young generation as a kind of hope for the future prospects of the community. They become ambassadors of propelling positive change within their community and for the people within it, which is why our second project centers around the children. Specifically, we continued the work of KFSP on the child health curriculum they curated, aimed at teaching children about the common public health issues in their community and to start sustainable initiatives and practices that the children can continue on their own, including teenage pregnancy awareness and permanent gardens.

Communication has been an aspect of leadership that I have been trying to be more conscious of after some issues with it led to the downfall of the management of a previous health project I co-founded. However, even after applying the lessons I learnt then, I realized its all-encompassing necessity exceeded what I’ve prepared myself for.

Being completely honest, our first mistake as a health team happened when we started the project. Quickly into the start of the project, we noticed tension build within the team, resulting in issues with motivations and misunderstandings of the aims of our work. If we continued our work that way without first tackling this issue, I doubt that we would have gotten to the point we’re at now. With some reflection, we realized that the issue lied in that, while we did have an initial discussion on what we wanted to achieve and how we wanted to achieve it, we never thought to begin by understanding each other’s individual visions and goals for the project. Instead, we took the words of our supervisor and assumed a common goal had been established, when really, there was great room for mismatches in expectations for the project and its process. Most importantly, we never took the time to understand our individual goals and how they could be incorporated into the vision of the project. Curiously, despite having missed multiple talking points, the latter two clearly became the gap that affected our work most as it seems to be the foundation of personal motivation, which drives dedication and inspired work into the project.

Catching this issue served as a kind of wake-up call to heighten my awareness of my communication, which I think is the main way I developed my leadership on this trip and is what I think of as the keystone to good leadership. It’s become clear to me that leadership inevitably involves people who may have different ideas, personalities, and strengths that need to be considered and these could either be played to the strength of the team if facilitated by communication or become a team’s shortcoming without.

Uganda was unfamiliar ground to me in ways more than just the people I worked with. As expected, it was an unfamiliar setting, where we were exposed to cultures and beliefs that we’ve never really heard of before, like the stigma against pregnant women using covered latrines rather than holes in the ground. So was there an entirely different set of resources that was available for us to work with. I am so grateful to have been involved in such innovative initiatives, such as the Reusable Menstrual Pads Project, which utilised materials that could be found easily for cheap in the region to make menstrual pads to tackle period poverty. With many of our other projects, I realise that being a leader also means resourcefulness. To be able to to solve problems with what is available at hand as solutions are not one size fits all. Different resources and contexts makes different solutions the most appropriate one. There was also something so empowering about helping the community find solutions that come from within the community, showing that it is capable of self-sufficiency and being independent of other bodies, may it be the government or us.

Despite my active involvement with the projects, only in retrospection did I get to recognise the most significant moral of leadership; the overarching theme of our 6-week venture. Each and every project we worked on were never planned to become a short-term gift to the people it targets but were planned to involve and empower these people to build themselves what they needed. The project is committed to creating a community that isn’t dependent on the project itself to receive its benefits, but rather to encouraging systems that generate self-sufficiency. Training the VHTs and providing them the resources to learn and work for themselves, teaching the children to build a garden that could provide them and their community with a balanced diet throughout the year, and many other projects all had the underlying aim of helping the community thrive from within themselves and be able to sustain these efforts independently, too. In this way, hopefully the impact of these projects can persist even after the projects themselves end.

The same goes for a leader. It is never their job to spoon-feed tasks or micro-manage each aspect of the project so as to show minimal trust in their members. A good leader empowers their members, encouraging them to believe in themselves and to have the passion and self-confidence to bring in new ideas that could work to enhance the outcomes. As we realised through our own work, the best way to do this is to talk. Understand each others’ goals, skillsets, and motivations to mold the project into something that plays to everyone’s strengths and becomes something they are all driven to accomplish, albeit in different ways.

Despite this “Leadership in Action” project intending to be a leadership experience for us, I was glad to know that, like myself, my fellow Laidlaw Scholars appreciated it more as an opportunity to make an impact for the Kibale National Park Community and were passionate for its cause. On reflection, I’m glad I can say that we spoke with the children and other members of the community, understood their needs, and, in all the work that we do, considered them first and foremost. We involved them in all stages of our process and left systems that they could maintain themselves far past the day we leave. I’m very grateful to have been able to learn so much about myself and leadership on this trip, but, most of all, I’m grateful to have met the children, the KFSP team, and the community. I truly hope we have made the impact the community hoped from us, but, I guess, only with time will we see if that’s so.

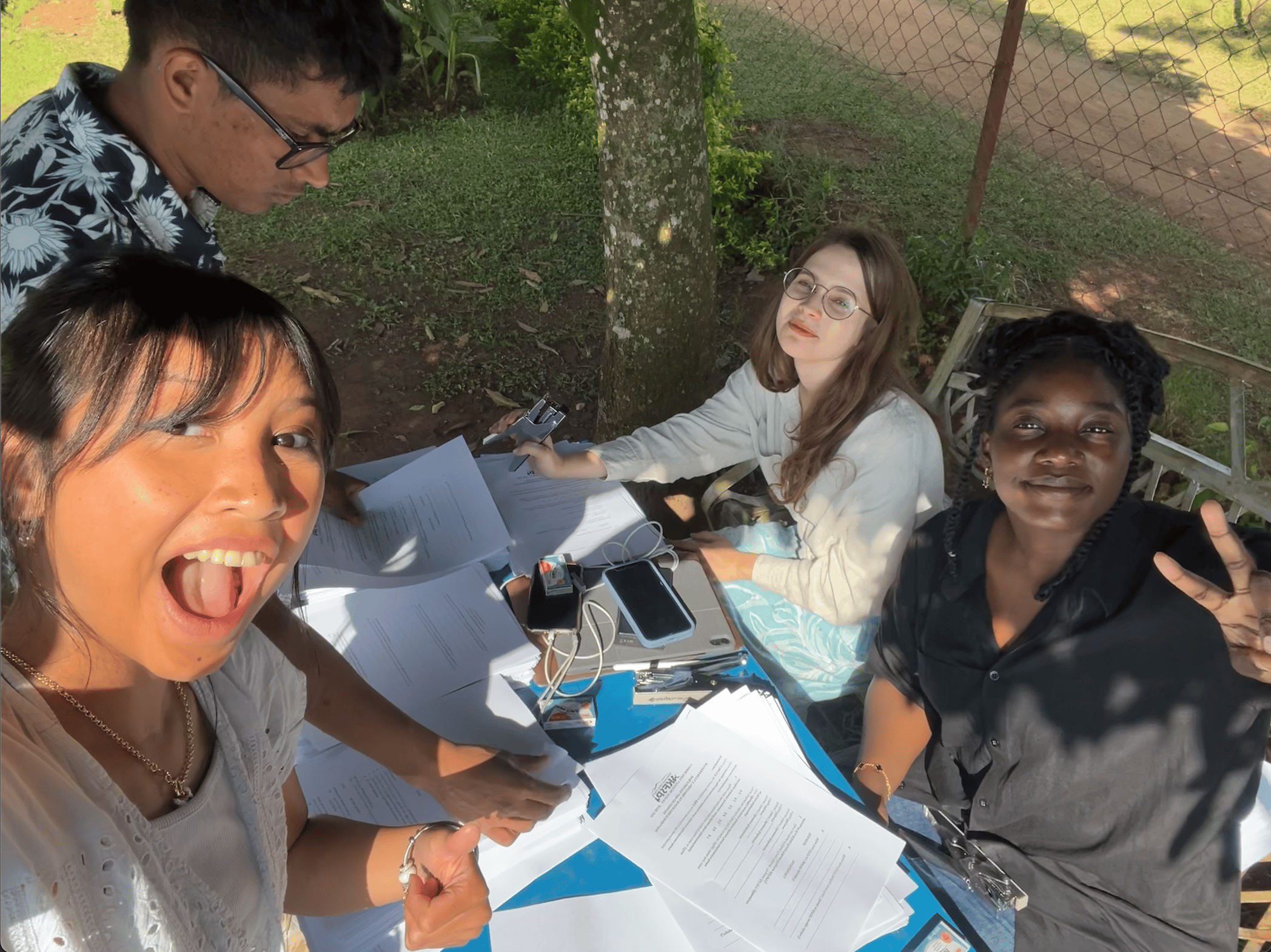

P.S. Due to lack of consent, I will not be sharing any pictures taken with the children and staff affiliated with KFSP. Also, please enjoy this picture of zebras.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in