Seeing Latin Leeds: Reflection on Research Project

Introduction

This project started with a broad question—what connects Latin America and Leeds?—and quickly focused on how Latin American visual arts ar e perceived through a UK perspective. I suspected a pattern of exoticisation, but the research uncovered something deeper: across clubs, festivals, university screens, and city museums, Leeds hosts far more Latin-inspired activities than is usually recognised. What may seem scattered at street level becomes clearer when viewed as a whole.

e perceived through a UK perspective. I suspected a pattern of exoticisation, but the research uncovered something deeper: across clubs, festivals, university screens, and city museums, Leeds hosts far more Latin-inspired activities than is usually recognised. What may seem scattered at street level becomes clearer when viewed as a whole.

The outcome is a public, online exhibition that categorises and analyses Leeds-based visual materials from the 1980s to today, including posters, flyers, festival programmes, museum displays, and collaborative works. The site features a graphical timeline and mini-archive that can be updated as new evidence appears. It also functions as a reader’s guide, offering a space to examine the colonial gaze in context, identify where it is reproduced, and demonstrate where Leeds reworks this lens through credit, context, and collaboration. Essentially, the project maps a largely hidden landscape and gives it an active, living presence.

Project Brief & Objectives

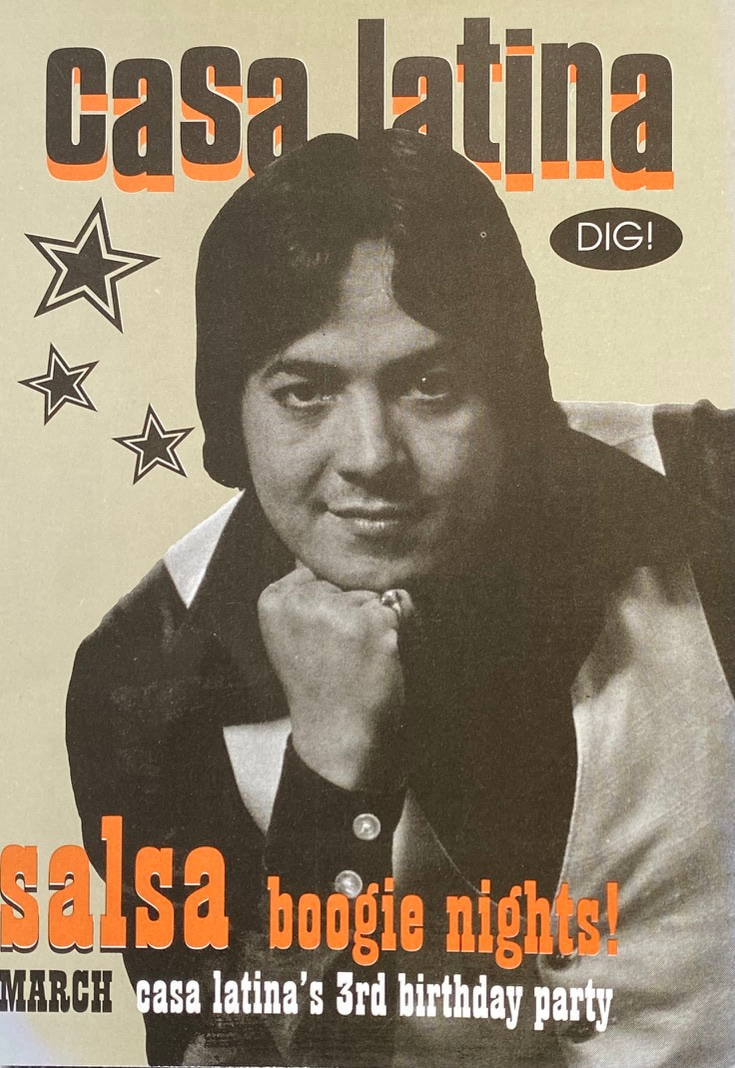

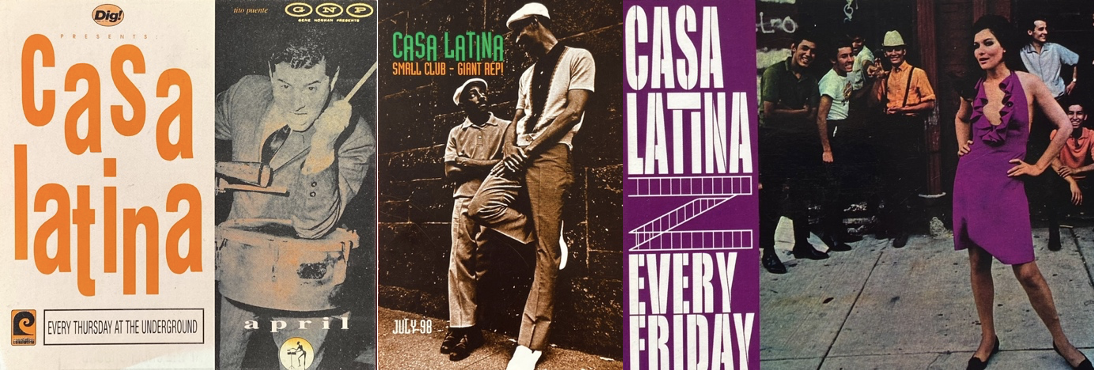

This project aimed to map connections between Leeds and Latin America through visual culture, focusing on how images, events, and texts shape perception. I focused on Leeds since the 1980s, when Latin-coded nights, community festivals, and university screenings began to leave visible traces. The specific areas of study include: community practices (e.g., parties and concerts promoted by Lubi Jovanović, now linked to Hyde Park Book Club and Brudenell Social Club), exoticisation in design and copy (branding that frames ‘Latin’ as heat/sensuality and collapses difference), and decolonial counter-practices (curation and pedagogy that add context, name authorship, and invite participation).

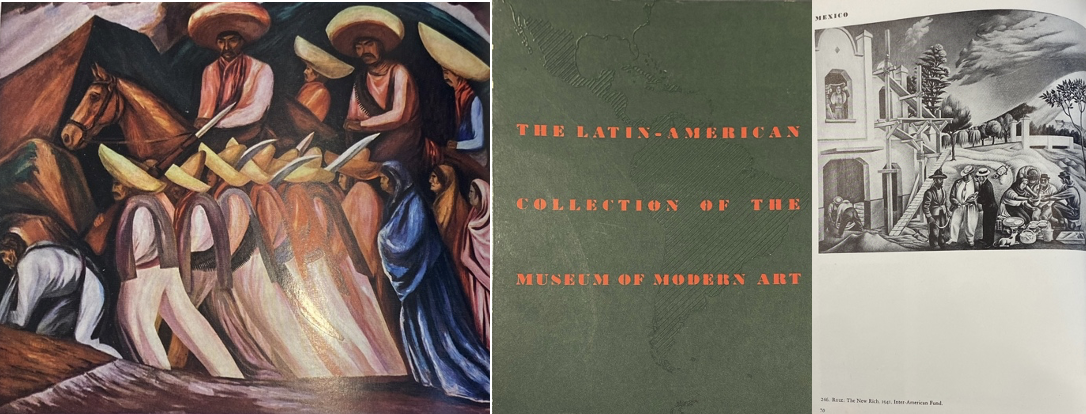

The main objectives were to document key artefacts and events (posters, programmes, museum displays, collaborative installations), analyse how the colonial gaze operated locally and where it was being reworked; and finally, to develop an accessible, evidence-based web exhibit that could grow with community contributions.

Due to time constraints, I was unable to secure ethical approval for formal interviews during this summer period. Rather than viewing this as a limitation, I adapted by working intelligently with the sources I could access: Brotherton Special Collections, public programmes, press materials, and university documentation, using informal conversations only as a guide. This approach ensured the project progressed within its timeframe while also laying a foundation for the future. Next year, with adequate planning for approvals, I aim to expand the work through formal interviews that will provide firsthand perspectives alongside the archival and visual evidence already gathered.

The intended outcome from the beginning was to create a public web exhibition—a curated timeline with evidence-backed case studies, short explainers on gaze/exoticisation, and a contribution portal for posters, photos, and memorabilia. The site is designed for students, programmers, and community members who need clarity, context, and citations, and it can expand as new materials emerge.

What Research I Conducted

Building on the brief, I conducted a thorough examination of the Brotherton Special Collections. The first weeks were humbling: I met de-contextualised folders, fragmentary flyers, and uncatalogued ephemera. The team were helpful, but provenance was often unclear; early leads stalled, and I felt I was mapping a city in the dark.

A supervision check-in—and guidance from Gregorio Alonso (co-worker of my supervisor)—shifted the project from ‘find every Leeds-LatAm link’ to a sharper visual-culture focus. We reframed my questions around how Latin America is seen in Leeds, and which practices reproduce or rework that gaze. With this lens, I moved to targeted desk research: scanning festival catalogues and press for Leeds International Film Festival (LIFF), Leeds Queer Film Festival and Vamos Leeds!; venue programmes from Hyde Park Picture House and the Howard Assembly Room; and organisational pages for Leeds Animation Workshop (LAW) and Women Make Movies (WMM). I also logged the 2023 ‘All that Lives’ collaboration (grief Series x Zion Art Studio) as a flagship case of co-created interpretation.

Armed with new keywords and names, I returned to the archives with purpose. This time, I located Feminist Archive North materials, Leeds City Council arts-funding files (Art@Leeds, grants to community/visual organisations), and LAW production/distribution records, as well as film-programme ephemera connected to local screenings. I began building a contact and events ledger: what happened, where, when, and who framed it.

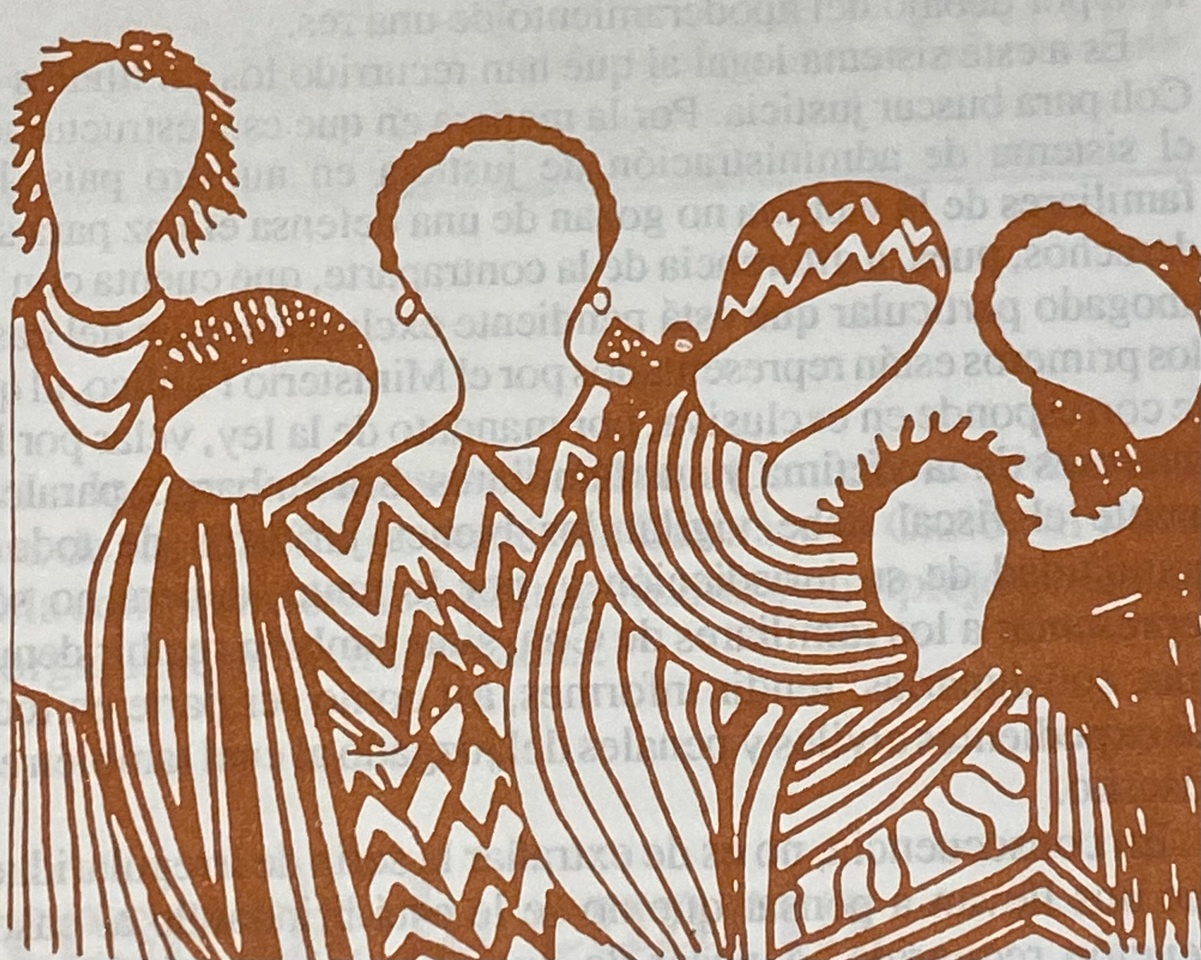

Next, I consulted academics and teaching artefacts to understand how spectatorship is taught locally. I contacted Prof. Thea Pitman, Dr Pete Watson, and Prof. Stephanie Dennison; I read module handbooks and relevant scholarship on exoticisation, the colonial gaze, and decolonial practice. In parallel, I added community artefacts: Lubi Jovanović generously shared flyers and posters from Casa Latina and subsequent nights, which I scanned, dated, and described. Each item received minimal metadata (date, venue, maker, theme/keywords, rights note), so it could slot into a public-facing collection.

The result is a work-in-progress website built around a single entrance page—an illustrated ‘room’ seen through a lens. Each object in the room is a future hotspot that clicks through to a dedicated page for one research stream: Community Visual Practices, Emotional Visuals, Visual Colonial Gaze, Branding & Exoticisation, and Feminist Distribution. On each page, findings are organised by timeline and theme, with digitised graphics drawn from Lubi’s posters, Brotherton/FAN scans, and programme/exhibition materials. Every item carries a caption, credit, and permissions note; short explainers translate theory into clear language; and the layout is designed to expand as new evidence and community contributions arrive (future upload form and analytics planned). This structure lets visitors enter through images and navigate out to context, rather than the other way around.

There were constraints. Without formal interviews, I relied on informal conversations only to orient searches and verify facts. Some avenues—like a complete reconstruction of student society records—proved dead ends due to missing documentation. I mitigated by triangulating events across multiple public sources (venues pages, archived press, festival catalogues) and by prioritising cases with clear provenance.

This workflow—archive to desk research to academic framing to community artefacts to public curation—produced not only an output but also a sustainable method for keeping the site alive as new materials emerge.

Impact and Importance

Despite an active history of Latin-American-inspired nights, screenings, and collaborations, Leed’s record is fragmented. Posters sit in shoe boxes, programmes disappear from venue sites, and community knowledge is passed informally. The result is a visibility gap: residents often assume Latin culture in Leeds is niche or recent, when the timeline actually shows depth and continuity.

The project addresses this gap by stitching together dispersed traces into a single accessible resource. For students and teachers, the site functions as a contextualised reader: objects are dated, credited, and annotated, allowing courses on film, languages, or museum studies to go beyond plot summaries and superficial impressions. For programmers and curators, it provides quick evidence—who created the work, where it travelled, and how to frame it responsibly—enhancing copy, post-film discussions, and partnership decisions. For community groups, it offers a recognisable reflection: a club flyer, city festivals, and public installations are displayed side by side, making it easier to identify where participation has been encouraged and where it can expand.

In addition to addressing the public visibility gap, the project also supports existing scholarship. By collating dispersed traces into a single accessible timeline, it provides a resource for students in Latin American studies, film, languages, or museum studies to ground assessments and research projects in local evidence. It also highlights what has previously been overlooked—namely, the role of small-scale community and feminist distribution routes in shaping cultural memory.

Finally, an equity perspective is integrated into the curation. Every page prioritises context, credit, and co-creation—the same principles exemplified by projects like ‘All that Lives (Grief Series x Zion Art Studio)’. Instead of treating Latin America as a decorative backdrop, the site names authors, explains rituals and languages, and highlights where Leeds is reframing the gaze through collaborations and pedagogy. In short, the work transforms scattered signals into a usable resource that encourages audiences to look again—and more fairly.

Dissemination & Engagement

The project’s public face is an interactive website/exhibition. It opens with a single ‘room’ image where each object will become a hotspot linking to a themed page. Inside each page, findings are organised by time and topic, with digitised graphics from Lubi Jovanović’s posters, Brotherton/FAN scans and programme/exhibition materials. Matrices summarise routes and actors, comparison and captions carry credits.

I have shared the work-in-progress through conversations with academics, venue and site visits, and by continuously ingesting materials from archives and community contributors. These exchanges refined the annotations and suggested new avenues for the timelines.

In the future, I plan to propose a roundtable discussion at SLAS 2026 and related forums. Attend SPLAS screenings and selected modules to gather curriculum feedback and identify gaps the site can fill. And add a simple contribution portal (posters, programmes, stories) with clear guidance on rights and credits.

Personal Impact

When I applied to the Laidlaw programme, I knew I was stepping outside my degree area; in the early weeks, I often felt as if I were doing someone else’s project. Yet as I read papers on Latin America, handled posters, and listened to how people in Leeds describe, admire or judge ‘Latin’, the material began to feel deeply familiar. This might not be my academic discipline, but it is my lived perspective as a Latin American who has studied abroad since I was sixteen.

That recognition did not remove the difficulties. It was my first time running research with a visible public outcome and limited permissions, uneven documentation and no interviews. I adapted by widening search methods, reframing dead-end questions, and asking mentors for direction when I stalled. The work taught me about a Leeds I didn’t know—its long, curious relationship with Latin America—and it taught me more about Latin America, too: archival fragments that testified to struggles I had not previously studied in detail.

Most importantly, the process taught me about myself- I learned that I can keep moving without perfect clarity, that I can revise my assumptions, and that I can translate complex ideas into public-facing forms. I shed some of my own stereotypes about how the UK ‘always’ sees Latin America, and gained confidence with primary sources, rights awareness and digital curation to build a site that others can use.

Challenges, Ethics & What I Would Do Differently

Building on the lessons I've learned about navigating uncertainty, I'd redesign the opening fortnight of a future project to avoid unnecessary dead ends. First, I'd establish a straightforward permissions process with a simple rights pipeline. I'd also run a concise reading sprint to clarify key concepts and create a keyword map before diving into the stacks—so searches start precise rather than exploratory. I'd define a single research question with subsections from the outset and enforce a consistent data scheme—so all the information is seamlessly integrated into the site and future updates are hassle-free. On ethics and attributions, if interviews are required, I'd initiate approvals early; if not, I'd publish a brief attribution note explaining how informal conversations inform the work without direct quotation.

These adjustments transform this summer’s experience into a repeatable method. More importantly, they directly guide the next stage of the project: ensuring future updates are built on clear permissions, precise keywords, and early planning, so the website can grow as a sustainable, long-term archive.

Leadership Skills Developed

Project leadership. I scoped the work, set milestones, and adjusted the plan as evidence appeared—moving from a broad idea to a deliverable site with timelines, hotspots and captions. I learned to balance ambition with time, and to version-control decisions so the exhibit can grow sustainably.

Stakeholder leadership. I practised respectful outreach—writing clearly to scholars, venues and artists; setting expectations about the lack of interviews; and keeping a live log of contacts, permissions and credits. This built trust and kept the project aligned with what partners could realistically share.

Ethical leadership. I centred credit, context and co-creation in the curation. That meant checking provenance, using only material I could properly attribute or describe, and adopting ‘collaboration without appropriation’ principles when presenting community work. I also wrote plain. Language notes about rights so future contributors understand how their materials will be used.

Communication leadership. I translated theory (exoticisation, colonial gaze, decolonial practice) into clear, public-friendly language supported by visuals and before/after comparisons. The site is designed for readers who may never open a journal article but can still learn to ‘look again’ with context.

Together, these skills turned a tentative start into a coherent public resource. They will also shape the next phase: maintaining the site as a living archive, refining its scholarly uses, and presenting the work at future forums.

Key Findings

Three findings stand out:

Community visual practices are lively—but fragmented. From the 1980s solidarity culture to today’s club nights and city festivals, Leeds has hosted far more Latin-coded activity than most people expect. Yet the record is scattered across flyers, venue pages and personal boxes, which means the history is easily lost. Branding often traded nuance for ‘Latin Heat’.

Leeds is reworking the gaze. Alongside the older branding, there are strong counter-examples: programme notes that credit Indigenous languages and collaborators; co-curated projects such as All that Lives; and university modules and screenings that teach spectators to read context before spectacle. Together, these practices name authorship, add history and invite participation, which measurably changes how viewers interpret the same image.

Feminist routes connect Latin America to UK screens. Local organisations and distribution networks have been quiet engines of circulation, linking Latin American filmmakers—often women—to educational and community exhibitions in Britain. Mapping these routes clarifies who moves work, where it travels, and how Leeds fits into UK-wide ecosystems.

Future Plans

I will maintain the website as a living resource, adding a contribution portal and simple analytics to track use. I hope I can present the work at SLAS 2026 and related forums, and continue attending SPLAS screening and selected modules to gather curricular feedback. I´ll expand the Feminist Distribution and Leeds timeline sections and map more routes. Longer term, I aim to keep working at the intersection of public humanities, digital curation and community collaboration, ensuring the resource remains open, credited and useful.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Anna Grimmaldi, my supervisor, for steady guidance and to Gregorio Alonso for the reframing that unlocked this project. Thanks to Tim Procter, the Interim Associate Director of Cultural Collections & Galleries at the Brotherton Library, for access to context and introductions. I also thank Dr Pete Watson and Professor Thea Pittman for academic insight and materials that sharpened the Leeds picture. Community contributor Lubi Jovanovič generously shared posters and memories that brought the 1990s-2000s to life. Institutional partners shaped the work in practice: The Grief Series, Zion Studios and Feminist Archive North. Finally, this research was made possible by the Laidlaw Research & Leadership Programme, whose support enabled a public-facing approach from start to finish.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in