Learning Opportunities in Kenya’s Informal financial Sector

Kenya’s ‘informal’ sector forms the backbone of its economy, with estimates suggesting it accounts over 75% of all employment.[1] Chamas (savings groups with normally between 10 and 30 members) prove vital for financing those ‘at the bottom of the economic pyramid’.[2] The structure of these groups is relatively simple. Members get together on a regular basis and each contribute a predetermined amount to a shared pot. The pot can then be used according to the rules decided on when the Chama was created.

The way the pot itself is used varies from chama to chama. Some simply save the contributions to in case of unexpected circumstances, some allow members to borrow with interest (ASCA) and some allocate the entire pot to one member each week on a rotating basis (ROSCA). Most of the chamas I have come across incorporate a few different uses for funds.

Despite the huge variety in the ways chama pots are spent, they all have one thing in common, regular meetings between members. This is where my summer research project focuses.

Those who have worked in an institutional or corporate setting before might be familiar with the term ‘town hall meeting’. A relatively informal meeting where ideas are openly discussed and questions encouraged. These meetings have proven benefits in supporting collaborative knowledge sharing and promoting organisational learning.[3] There is a great deal of literature supporting the importance of informal conversations and meetings as a means of knowledge building. It's not a huge leap from here to assume that these same benefits could be observable within Chama meetings, with their emphasis on equal decision-making and collaborative saving. This was essentially the crux of my research. I aimed to understand the structure of Chamas, the cultural context in which they exist and thrive and their potential knowledge-building benefits.

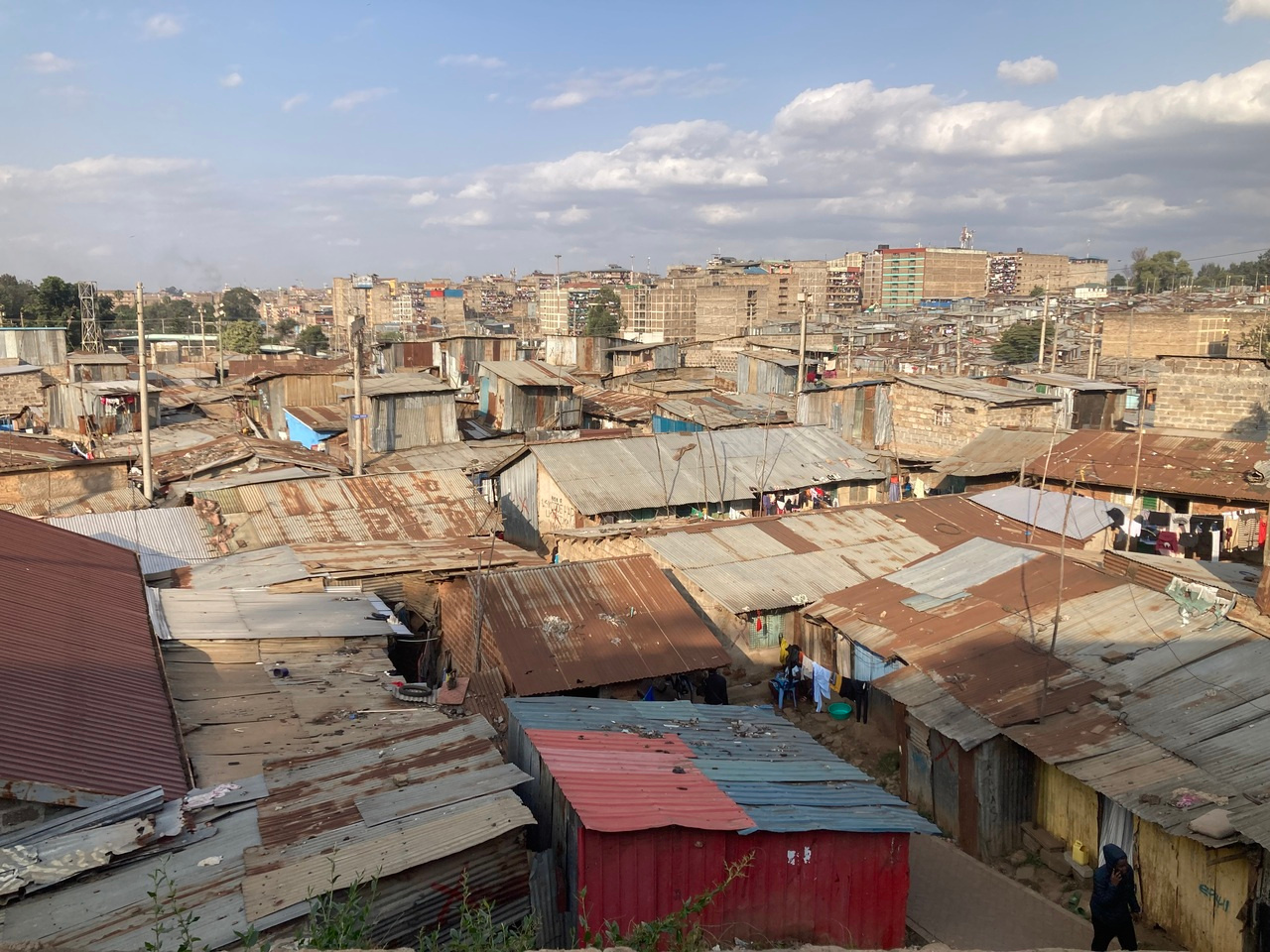

The research period for me was split into two distinct periods. My fieldwork at the beginning allowed me to speak to a wide range of people, from experts in the field to informal sector workers, who make up the main base of Chama users in areas such as Mathare and Kibera where my research focusses. This allowed me to get an understanding of the reality of Kenyas informal finance sector, hear stories about successful (and unsuccessful) Chamas and strengthen my network in Nairobi. This phase proved invaluable in shaping my understanding of Chamas and their social dynamics—something I discuss in more detail in a previous post.

The second part of my summer was more bookish. I moved to processing information from my time in Kenya and building my academic knowledge surrounding Chamas. During this time, I looked at the project from a range of different angles, including reviewing research from management studies, economics and anthropology to gain a holistic understanding of the landscape.

Chamas, or savings/table banking groups as they’re known more broadly, are not new, nor are they limited to Kenya. They are observable under different names in a huge range of economies, from India to South Africa. While there are a number of studies focussing on chamas and their role in these economies, there is very little making the link between their structure and the potential educational benefits. Where studies have been done, they seem to focus more on chamas as tools for teaching and spreading formal knowledge rather than generating it.[4]

While lacking the quantitative data to draw definitive conclusions, my findings have been exciting. The interviews ad conversations I had in Kenya suggest marked educational benefits of certain chamas and also point to further positives like community support networks. Overall, I feel this project has served as an effective pilot study for further research in the area.

I will update this blog post with a link to the project write-up once it’s finished.

[1] Murunga, James, Moses Kinyanjui Muriithi, and Nelson Were Wawire. 2021. “Estimating the Size of the Informal Sector in Kenya.” Edited by Christian Nsiah. Cogent Economics & Finance 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.2003000.

[2] Interview with Charles Ogutu, Online, 04-07-2025

[3] Mayfield , Milton. 2010. “Tacit Knowledge Sharing: Techniques for Putting a Powerful Tool in Practice.” Development and Learning in Organisations 24 (1): 24–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777281011010497.

[4] Henrik Nordvall, Wadende, P.A. and Amutabi, M.N. (2023). Swedish study circles encounter Kenyan chamas: a case study on the global interaction of traditions in non-formal adult education. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 42(3), pp.313–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2023.2201689.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in