My Project

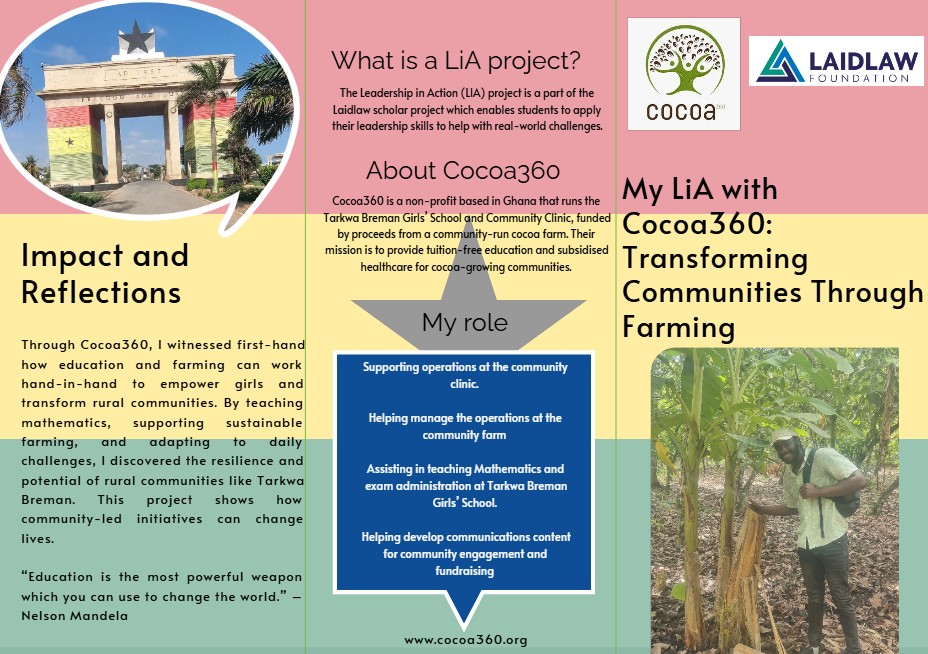

In 2025, I spent approximately four weeks in rural Ghana working with Cocoa360, an NGO whose mission is to leverage community-run cocoa farms to improve education and health (mainly in rural communities). This immersive Leadership in Action experience was based at the Tarkwa Breman Girls’ School (TBGS) and adjacent community health clinic. My role involved teaching mathematics to schoolgirls and supporting their sustainable farming operations. These tasks primarily focused on the following SDGs: SDG4 (Quality Education), SDG5 (Gender Equality), and SDG11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), which reflect Cocoa360’s objectives and broader global aims. I will explore the challenges encountered, the leadership skills applied and developed, ethical considerations, and collaborative dynamics. Throughout, I will share anecdotes and insights into how this experience has reshaped my approach to leadership and my future ambitions.

Challenges Faced

One of the most striking challenges in teaching was that many students struggled to focus in class. This was not due to a lack of interest or ability, but because of wider pressures on their lives. Many girls had significant family responsibilities, such as helping in shops, selling produce in the market, or taking care of siblings. These roles often meant they stayed up late, woke early, and arrived at school already exhausted.

Additionally, the heat and humidity of Ghana’s tropical climate made long days in classrooms physically draining. Without air conditioning or consistent access to cooling systems, it was common to see students becoming visibly tired and distracted in the morning. These challenges were symptoms of broader structural realities: rural communities rely heavily on children’s contributions to family businesses, and climate conditions are an inescapable part of daily life. For me as a teacher, this highlighted that student fatigue is not always laziness but can be the outcome of socioeconomic and environmental pressures. I learnt to adapt my teaching style to be more patient and to make classes more interactive so students could stay engaged despite these challenges.

Another recurring difficulty was the instability of electricity in Ghana, locally referred to as dumsor (literally “off and on”). Dumsor meant frequent and unpredictable power cuts, which affected both daily living and my teaching. I vividly remember one particular day when the electricity was off during a lesson. Without power, the fans in the classroom stopped working, and both the students and I quickly became lightheaded and unable to concentrate in the heat. What would have been a simple maths lesson on Pythagoras' theorem turned into a test of endurance. These outages were a daily occurrence, and the time they spanned ranged from a few minutes to many hours; they stem from infrastructure limitations and high national demand that exceeds supply. Experiencing dumsor first-hand made me appreciate the resilience of teachers and students who continue learning despite such obstacles. It also forced me to adapt by encouraging students to take small breaks to cool down. These moments reinforced my appreciation for resilience in leadership and taught me to lead by staying calm and resourceful, even when circumstances were out of my control.

Physical demands were also a challenge. Weeding a cocoa plot under the sun tested my endurance. I approached farming tasks respectfully, following Ghanaian farmers’ guidance. When I struggled to cut some weeds, a local farmer gently corrected me. From this, I learnt adaptability and humility: by the end of the week, I could weed cocoa trees correctly, but more importantly, I realised that sustainable agriculture requires patience and community knowledge.

Leadership Skills Applied and Developed

Throughout the placement, I applied a wide range of leadership skills, each of which developed further through the challenges I encountered. Communication was one of these skills. Teaching mathematics to students who were often tired or distracted required me to simplify concepts, use relatable local examples, and adapt my delivery style. In addition to this, I had to change my usual vocabulary as some words I would commonly use in the UK were not widespread in Ghana, and English was not the first language of the students. This shift taught me that effective communication must take into account first and foremost the audience and their changing nature, and it must be constantly rethought to match the audience’s context. By the end of my placement, I had grown more confident in flexibly tailoring my style, a skill I can now apply in any future leadership or teaching role.

My problem-solving and adaptability skills also developed. On the farm, when confronted with tasks that were unfamiliar and physically demanding, I first struggled. But by observing, asking for help, and practicing, I improved my technique and stamina. This experience helped me see problem-solving as a patient process, not just a quick fix. In the classroom, dumsor and limited materials forced me to improvise, such as creating interactive activities or using a whiteboard drawing to replace absent visual aids. Each time I found a solution under pressure, my resilience and creative thinking grew stronger.

Additionally, my teamwork and collaboration skills also improved. Working alongside local teachers required me to balance my ideas with respect for their established practices. At first, I was hesitant to suggest changes, but gradually I learnt to offer input while valuing their expertise. This dynamic helped me develop the humility to both lead and follow, depending on the situation. By co-planning lessons and sharing strategies, I became more effective at collaborating across cultural and professional differences.

One unique aspect of this placement was cultural humility. Stepping into a Ghanaian rural community, I had to constantly check my assumptions. For example, I assumed classroom discipline would be similar to what I knew, but I quickly learnt that Ghanaian classrooms are often more communal. For example, when I asked the students a question, they would prefer to give answers all together as a class. I realised I needed to adapt. Rather than insisting on my method, I shifted to more call and response and group problem-solving, which resonated with them. This taught me not to forcefully impose my cultural norms wherever I go.

I also confronted personal biases. Before arriving, I had a vague expectation of traditional rural life. I was humbled to discover a dynamic culture full of warmth and wit. Simple gestures like learning to greet people I meet in Twi (local language) opened doors. I listened to girls who shared their dreams of growing up and going to big cities and university, despite coming from farming families. These conversations broadened my understanding of education’s role; I learnt that these girls prized learning as a path to see more of the world, teaching me to appreciate education’s local meaning. At the community clinic, I listened quietly to patients’ stories of illness and their reliance on Cocoa360’s subsidised care. This deep listening reinforced to me that leaders must learn from those they aim to help.

I discovered that this work was about recognising the shared curiosity and traits that make all of us on earth similar. I found that when I entered the classroom with openness (rather than authority), students became more engaged. For instance, after one lesson, a group of girls stayed late to ask questions about my culture and how it differs from their own, a sign that they felt comfortable around me. This required me to explain some cultural and economical differences between the UK and Ghana without coming across with a pompous attitude. It needed humility. Thus, I kept my demeanor humble, honest, and understanding. Over time, these cross-cultural interactions taught me empathy. I became more aware of cultural differences in lifestyles as well as mindsets, and tried to meet them in the middle.

Overall, cultural humility meant accepting that I am the learner in a new cultural setting. I challenged my own preconceptions every day and welcomed corrections. This openness enabled genuine connection. By the end of the four weeks, I was greeting staff and students in Twi, sharing local jokes, and truly appreciating that leadership often comes from showing respect and willingness to learn.

Ethical Considerations

During my placement, two prominent ethical issues stood out: disciplinary practices in schools and the challenge of illegal mining (galamsey) in rural communities. In several schools, the use of physical punishment, such as the cane, was still practised. While this is considered normal and acceptable in the local context, it raises significant ethical questions for me, as it conflicts with safeguarding standards and child protection policies I am familiar with in the UK. Observing this highlighted the difficulty leaders face in balancing cultural norms with international standards of child welfare. It challenged me to think critically about how to respect local traditions while also upholding the principle of protecting the dignity and rights of students.

Another ethical dilemma arose from galamsey, a widespread practice of illegal mining that severely impacts both the environment and the livelihoods of the community. Contamination from these activities destroys local sources of water, making it harder to grow crops and also causes birth defects in these communities. also threatens the long-term sustainability of farming communities since arable farm land is often given up to use for galamsey. Here, the ethical conflict lies in understanding the desperation that drives individuals to turn to galamsey for short-term survival, while recognising the devastating long-term harm it causes to the community and environment.

Together, these issues taught me that ethical leadership often involves navigating cultural sensitivity, immediate human needs, and future sustainability. They underscored that ethical choices are rarely straightforward; instead, they require empathy, respect, and the courage to advocate for practices that safeguard both people and the environment.

Collaboration and Team Dynamics

Working with diverse groups of people was one of the most rewarding aspects of my placement. I collaborated with teachers, students, healthcare professionals, and local farmers, each of whom brought unique perspectives and expertise. In the classroom, collaboration meant adjusting my teaching style to complement the approaches already used by the school’s staff, while also creating an environment where students felt comfortable engaging with me. On the farm, teamwork with local farmers demonstrated the importance of trust and patience, as I relied on their guidance to learn agricultural practices I had never encountered before. This reminded me of the importance of mutual understanding when working in a team.

Interactions with staff at Cocoa360 also highlighted the value of clear communication and shared responsibility. For example, during administrative tasks such as marking work and aligning the sustainable development goals to their programs, I saw how structured collaboration helped ensure efficiency and accuracy. Moreover, conversations with students where we taught each other about music and language revealed how mutual respect and openness can build strong bonds even across cultural differences.

Overall, these interactions taught me that effective leadership flourishes in a collaborative environment. I learnt to listen actively, value others’ expertise, and empower teammates. In doing so, I witnessed a leader’s role as facilitator: setting direction while enabling everyone to contribute their best.

Conclusion

My Leadership in Action placement in Ghana was an experience of personal and professional growth. I learnt first-hand about the resilience, adaptability, and empathy that leadership requires. Additionally, engaging in a teaching and farming initiative showed me the importance of aligning leadership with the needs of the people being served.

The placement reinforced that ethical leadership is grounded in respect and responsibility, while effective collaboration depends on building trust and working towards shared goals. Above all, I was reminded that true leadership is not about individual achievement but about the achievements of the group.

These lessons will shape my future leadership practice by reminding me to prioritise ethical reflection, cultural sensitivity, and collaborative problem-solving in every context. Whether in professional or informal settings, I will carry forward the humility, resilience, and commitment to sustainability that this experience instilled in me.

Acknowledgements:

I am grateful to all those who supported this journey. Special thanks to Cocoa360 and its staff for welcoming me and providing guidance throughout the project. I also thank my LiA advisor, Ruby-Anne, the Laidlaw Scholars Foundation, and Oxford SDG Impact Lab for their funding, training, and support of this Leadership-in-Action experience. Together, their support made this transformative experience possible.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in