Freedom to Think

For the entirety of my academic career so far, learning has been tightly linked to pressure. Exams, deadlines, university admissions and general competition between peers often caused me to dread the classroom environment. Over the course of each academic year I felt the passion and enjoyment for my subject seeping out of me, as my focus turned to getting through the exam period. Combined with the knowledge that as a medical student this will continue for the foreseeable future, it is easy to lose the joy that I felt in school as a child.

Completing my research project has reframed the way I think about education.

Over the last six weeks I have been investigating the mechanisms of activation of antimicrobial resistance in a specific strain of Staphylococcus aureus called MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus). Bacterial DNA is partly stored in circular loops called plasmids. These can be used to insert genes into the bacterium, for example allowing resistance to a specific antibiotic, alongside reporter genes which produce fluorescence or other effects when the gene has been successfully inserted. Under the guidance of my supervisor I have been working with six plasmid-based reporter constructs: three introduced into Escherichia coli and three into Staphylococcus aureus.

We hypothesised that the interactions between mobile genetic elements - specifically prophages and PICIs - influences the activation of resistance genes. Reporter constructs allowed us to investigate the interactions between these.

As my introduction to the working world began I spent 8 hours each day in the laboratory alongside a fellow scholar, learning techniques from basic pipetting to gel extractions. Initially I was consistently overwhelmed - as a medical student we don’t have much exposure to the lab and the microbiological concepts I was expected to be proficient in aren’t covered until the third year of my degree. I would return from the lab exhausted, unable to socialise or read around my project due to the mental stress of being constantly tested and subsequently confused.

Then on the 9th of June, strange things started to happen. I expected one of my plasmids, pAH0874, to grow on a plate overnight. But it did not.

Over the next 4 weeks pAH0874 would become my worst enemy. I repeated PCRs and gel electrophoresis and in my stress, made more mistakes over and over again. Nothing seemed to work. I almost broke into tears multiple times in the lab, and was incredibly grateful for the kindness, patience, and reassurance from my lab partner Ishani and guidance from my supervisor. I searched for the source of the unexpected results with no avail.

Finally, on the 19th of June I found out through DNA sequencing that the results I was looking for in endless repeats could never be obtained. I had made a simple mistake, seemingly at the very beginning of my project, which influenced each following reaction. The first 3 weeks of my research period felt as though they had gone to waste.

This process tested my patience, interest in microbiology and determination over and over again. At times I wanted to abandon 874, pretend it never existed. This may sound similar to my academic career that I described at the beginning, but instead I felt it was intrinsically different.

What surprised me the most was how inspiring learning felt without the looming pressure of an assessment. In the lab my mistakes weren’t the end of the journey - they were expected as part of the scientific process, as part of learning. My supervisor was guiding and patient to allow me to repeat my experiments over and over again, until at last it was right. pAH0874 did end up producing the results we expected, after going back to the drawing board and starting again. As a result I think I could now perform the complex procedures of annealing, ligation and transformation in my sleep. Each day brought a new technique to master, a fresh result to puzzle over, and often, more questions than answers. Returning to my childhood self I wasn’t learning to pass a test - I was learning to understand.

This shift in mindset is something I hope to carry forward into my studies. I have learnt to be okay with sitting in the uncertainty and asking good questions. I am beyond grateful for the space to learn from my mistakes and reignite my passion for learning.

References

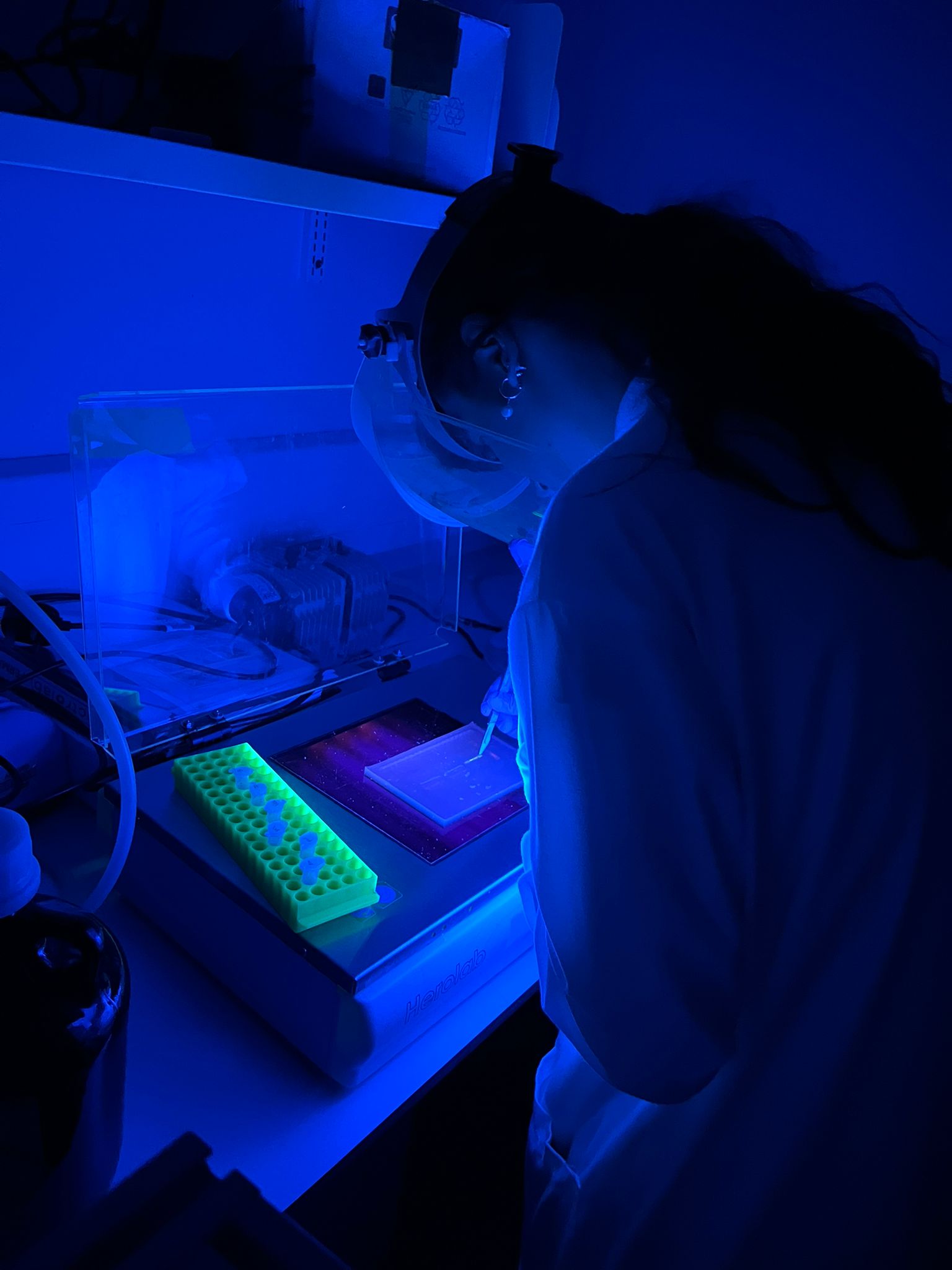

Purkis, M., 2025. [Untitled photograph]. Taken 9 July. Accessed 11 July 2025.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in

Brilliant blog Orla! So interesting to read more about your project and the challenges which you have managed to overcome! Thanks for the citation too :)

I'm glad to hear that Laidlaw has given you a chance to work in the labs, and make mistakes, without the pressure of an assignment like normal class would. While it sounds like a frustrating journey, I hope its also been a rewarding one! You'll look back on this someday as a turning point I bet!