What Romania Taught Me About the Future of Reproductive Rights in America

This summer, in Italy, I pored over decades of demographic data, trying to understand what happens to a society when reproductive rights are restricted. Back in the United States last summer, I witnessed a similar story unfold through court rulings, state legislation, and cultural shifts.

Last summer, I started by researching the recent changes in reproductive rights laws across several U.S. states. Since the fall of Roe v. Wade, states have been left to decide the future of abortion access for themselves, resulting in a legal patchwork that is already influencing women's lives across the country. But one of the challenges I faced early on was how to measure those effects. Policy debates often center around abstract values and legal principles. Still, I wanted to know: What are the real consequences of these laws for population growth, women’s education, and workforce participation?

To get a clearer picture, I turned to Romania, a country with a deeply complex history of reproductive policy. In 1966, under Nicolae Ceaușescu’s communist regime, Romania implemented one of the most extreme anti-abortion laws in the world. Contraceptives were restricted, abortion was banned, and women were monitored for fertility. Birth rates initially spiked, but so did maternal mortality, child abandonment, and illegal abortions. In the decades that followed, Romania’s policies swung back and forth between restriction and liberalization.

In recent years, Romania’s reproductive landscape has shifted again, this time not through sweeping legislation, but through a quiet erosion of access. While abortion remains legal up to 14 weeks of pregnancy, a growing number of doctors and hospitals have begun refusing to perform the procedure, often citing conscientious objection. This has created a patchwork of availability that leaves many women unable to access care in practice, even if it's permitted in law. The government, facing concerns about population decline, has subtly encouraged pronatalist attitudes without enacting overt bans. This chilling effect, where legality exists in theory but not in practice, reflects a more diffuse form of restriction that still carries serious consequences. It mirrors a trend now emerging in parts of the U.S., where legal ambiguity and provider hesitancy are beginning to reshape access in similarly uneven ways.

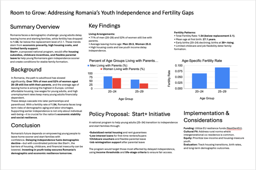

Today, the country’s demographic trends tell a layered story about how reproductive rights shape not only individual lives but the fabric of an entire society. I should note that the comparison between Romania and the US remains very general and does not necessarily account for the effects of emigration and immigration within and between the respective countries.

I studied Eurostat data to trace these patterns: what happened to women's employment rates when restrictions were in place? How did education outcomes shift when women had fewer choices? Was the impact immediate, or did it unfold slowly over time? What’s interesting about Romania is that it holds two distinct populations of women, one where abortion was accessible after 1989 and one where abortion was inaccessible between 1967 and 1989. A population trend that is beginning to form in the US as women enter the workforce and education in a country where abortion is restricted.

What struck me most was how eerily some of these patterns echoed what's beginning to happen in the U.S. While we’re still in the early stages, data from states with restrictive laws is already showing changes in women’s mobility, healthcare access, and economic behavior. The social shifts I saw in American headlines felt like an inverse of a longer story that had already unfolded in Eastern Europe.

Comparing Romania’s past with the U.S.’s present helped me ask better questions. For example, if Romania's restrictive policies ultimately harmed public health and slowed progress for women, why are similar approaches being revived elsewhere? Are the demographic consequences inescapable, or can countries learn from each other’s histories?

This experience also altered my perspective on policy research. It's easy to treat data as cold or impersonal, but behind every data point is a real person navigating complex systems. A drop in birth rates isn’t just a number. It reflects the changing choices, shifting trust in institutions, and the lived experiences of millions of women.

There were moments during my research in Italy, where I was based while accessing European archives, when the contrast between the U.S. and Europe felt especially sharp. In many European countries, reproductive rights are protected as part of a broader social welfare system. The debates are far from over, but access to reproductive healthcare is often framed as a matter of public health and economic stability, not just personal morality or legal precedent.

By studying Romania’s past and Europe’s present, I gained perspective on the U.S.’s future. I came away with more questions than answers, but also with a renewed sense of urgency: reproductive rights aren’t just about individual choice, they’re about how societies invest in their futures. The laws we pass today will shape generations.

As I return to my studies and continue this research, I carry with me a deeper appreciation for the power of interdisciplinary work. Demography, law, gender studies, and economics all intersect in this project. I’ve learned to hold complexity, to ask uncomfortable questions, and to seek out patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed. Most of all, I’ve learned that history doesn’t repeat itself in the same way, but it rhymes. And if we listen closely, we might hear the echoes before the consequences arrive.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in