Tashkent- the fabric(s) of a city of bread

Non is everywhere in Tashkent- every street corner, every shopping list, every carrier bag, and on every table. Asking for no bread in a restaurant is like asking for no cutlery, probably stranger. I was given bread by co-workers married to bakers, and by stall holders who had already given me their time- in conversation and in trying to find me a local wife. Bakers showed me how to make it and then gifted me bread too fresh to touch. The loaves with a story behind them were always the ones that tasted the best.

Non is usually sold from trolleys, that look a bit like prams, draped with blankets to shield from the midday sun. Bread is only ever baked by men, but the sellers range from elderly ladies to young boys, and each in Tashkent specialises in a regional variety. Samarkand non glistens and is dense and heavy. Pattir from Ferghana is flaky, buttery, Tashkent non is crustier. Some are adorned with patterns and seeds, others with dried onion or filled with meat. Uzbek bread is round, usually raised with an indent in the middle, but you can buy rye non inspired by the north, flatbreads in table sized (Afghan) and small (Turkish) form, as well as sourdough from Paul (yes, that French bakery you see on every central London street).

Every city has a character, look, pace of life, culture, set of values, history. It is impossible to define what a “city” is- each one is a unique animal, and it is their complexity that gives them energy and perpetuality. So, it wasn’t just for non’s ubiquity or variety that Tashkent was first called «Город хлебный» (“City of Bread”). It has always been a way of life here, but it was the writer Neverov who coined the name for his 1923 novel. It described how Tashkent became a haven for refugees from the Volga region, fleeing the famines caused by the Russian Civil War. They were the first of many to seek refuge in this city. Anna Akhmatova was among the thousands of evacuees, many artistic and intellectual elites, relocated here under Stalin’s orders during WWII. The next came after the devastating earthquake of 1966, when thousands of Soviet citizens were incentivised to move to Tashkent and help the city rebuild. The latest influx- Russians, often young men, alone, fleeing mobilisation in Putin’s war in Ukraine. The sharing of Uzbekistan’s bread, and land, with strangers, again.

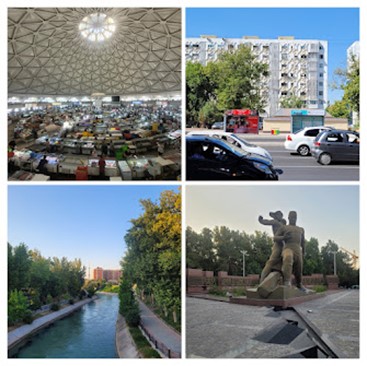

A hunt for bread naturally starts in Chorsu Bazar. The centre of the old city, records of which date back to the 3rd century. For all the talk of growing conservatism in the east of the country, it is here, one baker’s wife tells me, that the real traditionalist Uzbekistan lies- a little insular, generally religious, linked by ancient bonds, even if most now live in five or nine storey apartment blocks, built under Soviet authority.

These blocks are almost never more than nine stories- the highest that natural gas can reach. But function didn’t always come over form. The devastating earthquake of 1966 flattened much of the city, though very few died- the traditional houses built of clay and wood simply crumbled. The challenge of housing new and old residents brought innovation, and the mahallas were replaced by a new tradition- “Tashkent Modernism”. Conceived both by local and Muscovite architects, the style reflects the tension between the Soviet desire to build their ideology, and to develop a local, “oriental” style. At a lecture dedicated to the preservation of these brutalist masterpieces, the generational and ideological divide between those who value these buildings, and those who do not, becomes clear.

Both in politics and in nature, only those with the power to preserve can decide what should remain. The destructive earthquake left room for a new, green Tashkent, one that is centred around parks and canals. Despite its many ecological problems, and the blazing sun, it is a green city. But this does not make it natural- as in many cities around the world, this has become a part of the hierarchy of power. A large chunk of the central park is fenced off, hectares of green central Tashkent surrounded by police cordon, since the new president chose the buildings in the centre for his home.

Beyond this are the skyscrapers of “Tashkent City”- the chain hotels, half empty office blocks, and meticulously landscaped parks of every globalised city. Costa, ethnically Ukrainian but born in Tashkent, owns a coffee stall on the Parisian style “main street”. I’m the only customer for the hour that we sit and drink espresso, talking about how the money invested in this district could have been better spent elsewhere.

I’ve separated these districts and periods out, but really, they are not so separate. They merge and morph into Tashkent. I drink tea with youth activists outside street food stalls, on the corner of a Soviet development. Eat handmade Uighur noodles in the food court of a shopping centre. I see vibrant water fountains in every public square, going between meetings on Uzbekistan’s impending water shortages. And I buy bread from a pram outside the Ministry of Ecology building, where inside I read policy papers on the urban environment’s role in human development. To feel a city, you walk it, taste it, and make up metaphors to understand it. But it is the complexity of cities that we value, the way that they surprise and confuse us. They sometimes scare us and often divide us too. Tashkent is no different. It can carry you away, and then take you in- a city of bread.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in