Rewriting History - Shirley Thompson OBE

Listen to #TheGoodLeader on:

Don't forget to like this post, comment, subscribe, and share!

Description

Dr Shirley Thompson OBE is a contemporary classical composer, artistic director, and academic, as well as a known trailblazer and cultural activist. She has forged her own way and created her own voice in musical composition, referencing her Jamaican heritage and the histories of Africa, the Caribbean and the experiences of persons of African descent in Britain.

In 2004, she became the first woman in Europe to have composed and conducted a symphony within the past 40 years - New Nation Rising, performed and recorded by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. In 2019, she was awarded an OBE for her services to music.

She was recently appointed Professor of Music at the University of Westminster, and featured as one of the changemakers in The Guardian's 2,000-year history poster of critical events & activists. Dr Thompson has been named in the Evening Standard’s ‘Power List of Britain’s Top 100 Most Influential Black People’ from 2010 to 2020, with the highest position of number 8.

In this episode of The Good Leader podcast, Dr Thompson discusses her extraordinary story of success and how she has been using classical music to tell stories and rewrite accepted narratives, changing the representation of women and persons of visibly African heritage in history.

Follow Dr Thompson on SoundCloud, Twitter, and YouTube.

Visit Dr Thompson's website here.

References

Dr Thompson's timeline for BBC Radio 3

Postcard for BBC Radio 3 - Breakfast

The Woman Who Refused to Dance

Minerva Scientifica - The Franklin Effect

Memories in Mind: Women of the Windrush Tell Their Stories

Shirley's profile on Deuss Music

Storytelling with the Power of Music - A 21st Century Symphony: Shirley J. Thompson at TEDxJamaica

Transcript

INTERVIEW EXCERPT: People just don’t even question it but I did question it and I think, at the time, I was the only person asking those questions. Because even now I go to major conferences and people aren’t asking those questions and I am asking those questions. So, the questions are just being asked for the past couple of years or so but I’ve been asking them since the 80s.

NIKOL CHEN: From the Laidlaw Foundation, I’m Nikol Chen and this is The Good Leader - a podcast where we talk to remarkable individuals in all sorts of fields to learn more about how to lead with integrity, and explore what the next generation of leaders is doing to solve the world’s most intractable problems. Our first season is all about the ins & outs of navigating the world of leadership as a woman.

I’d like you to think of three famous classical composers you know. [pause] Now, how many of them are not dead white men? Probably none. In fact, can you think of a female classical composer? Or a composer who is a person of colour? I doubt it.

Our special guest today is an incredibly talented, bold, and innovative classical composer, artistic director, and academic, as well as a known trailblazer and cultural activist. In 2004, she became the first woman in Europe to have composed and conducted a symphony within the past 40 years - New Nation Rising, performed and recorded by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. And in 2019, she was awarded the OBE for services to music. Here is New Nation Rising…

[audio excerpt of New Nation Rising: A 21st Century Symphony]

I am absolutely delighted to welcome Dr Shirley Thompson.

Throughout her career, Dr Thompson has forged her own way and created her own voice in musical composition, referencing her Jamaican heritage and the histories of Africa, the Caribbean and the experience of persons of African descent in Britain. She has also been asked to compose for notable public and royal engagements, such as Commonwealth Day, performing for HM Queen Elizabeth at Westminster Abbey in 1999, the commemoration of the Queen’s Golden Jubilee in 2002, the opening of the Parliamentary exhibition, British Slave Trade: Abolition, Parliament and People in 2007, and the commemoration of 100 days of Barack Obama’s Presidency, commissioned by the Southbank Centre.

Dr Thompson has served for over 20 years in several national arts institutions, including the London Arts Board, the Arts Council of Great Britain and the Newham Council Cultural Forum. She was the first female executive of the Association of Professional Composers and now serves as an elected member of the Classical Music Executive for the British Academy of Song Writers, Composers and Authors. She was recently appointed Professor of Music at the University of Westminster, and she has been named in the Evening Standard’s ‘Power List of Britain’s Top 100 Most Influential Black People’ from 2010 to 2020, with the highest position of number 8.

A quick note before we begin: the interview was recorded at the end of March - just as lockdown in the UK began, but before the wave of US national and global protests against police brutality and racial injustice.

Here is Dr Thompson.

NIKOL CHEN: Dr Thompson, thank you so much for talking to me today.

SHIRLEY THOMPSON: You are welcome, Nikol. I’m really happy to be doing this interview.

NC: I’d like to start off with a quote from one of your past interviews, in which you said: “I thought Beethoven and Bach were composers, I didn’t think of myself as a composer.” Could you give some context for this, and when did you begin to see yourself as a composer?

ST: Interesting that you’ve picked that up...I think I had just left university. I had just taken my Master's degree, and I was getting, very fortunately, I was getting commissions. But having just come out of university and being a student, I didn’t see myself as a professional musician at that stage because I had been in academia.

And I hadn’t even thought of myself as a composer because, in those days, you looked up to people who had achieved a certain degree of recognition. So, the people who had recognition for me were Stockhausen and Birtwistle and Bach and Beethoven. They had recognition. So, for me, you needed to have something of a profile before you were called a composer. There’s no professional qualification as a composer.

What I didn’t realise is that there is peer recognition as a composer. I think it was after my first professional engagement at the Royal Festival Hall, a friend of mine, whom I did call a composer because he was years ahead of me and had had several performances, and he was a bit of a mentor at the time, said “Oh, you’re going to make a really good composer.” And I thought “Oh, composer? Haven’t really thought of that...I’m just writing music and getting it performed as usual, as I had been as a student.”

NC: And did you have any role models growing up or while studying music at university?

ST: Not especially. I mean, I enjoyed so many subjects - I just loved learning. So, my role model was really the idea of the Renaissance person - the idea of someone who is accomplished in many things really appealed to me. That was my barometer for achievement. I saw myself as being able to achieve whatever I put my mind to - so, if I wanted to be a doctor, I could be it. If I wanted to be an athlete, I could be it.

So, I aspired to ideals rather than any particular person. I’ve always admired my mother greatly because I think she strived very hard with little means to achieve what she did and I think she did amazingly well with her qualifications. And she had to learn to do everything for her to be able to have children and then she went on to train to be a nurse. And so, that was my role model.

NC: Speaking of your mother, I read that when you were 14, the National Sports Association of the UK made your family an offer to train you professionally to represent Great Britain but your mother turned it down - is that true?

ST: Yes, I was invited to join the county team. I remember a letter coming from Scotland for some reason and I was invited to join the county team to train as a sprinter. I was a very good 100m sprinter and a high jumper. I mean, for my age group, I was always achieving results that were 2 or 3 years ahead of my age group. And I had always been very sporty - netball team captain, athletics team captain, many things. So, yes, my mother said “No, I think you’re better off pursuing your academic work rather than running.”

My mother had high expectations for all of us. Well, I just think she had expectations that we would achieve in school and reach our full potential. She just had that expectation for all of us and really valued our education very much and made every effort to make sure we had, in my day it was encyclopaedias - we had all of the Britannica encyclopaedias in our house, which were, at the time, literature and resources that schools had, but we had it in our house. So, she really pulled out all the stops to make sure we had every access to achieving our educational goals.

NC: And in the same interview I referenced earlier, you also said that you weren’t quite aware of systemic racial injustice until you were 10 years old, which is when you were sent to, as you said, an ‘awful’ school, compared to your white classmates who were sent to good schools. Could you tell me more about that?

ST: Well, I was only a child - I was 10 years old. So, it’s a bit sad that I had to become aware of social injustice at 10 years old, I think. Yes, I was happily enjoying school and everything. I was always at the top of my class, I was always good at sport, I was always good at music, I led my school orchestra, I was always good at lots of things.

But when it came to going into the next level of school, I was told that I would be going to a particular school that all the lesser-able students were going to and all my friends...I was in an A-stream class and I think I was the only one from that class that was being sent to this other school, and all my other friends who were white could go to any good school they wanted to go to. But I had no choice. I was just sent to this school that was not known for academic achievement. It was known for producing people for factories, and retail and stuff like that. You weren’t expected to achieve academically, basically, and I was an academic from an early age.

So, I was devastated. I mean, as a 10 year old, you don’t know what to do. You were just shattered. I was absolutely shattered. I didn’t know if it was injustice - I knew something was wrong but you don’t know anything of the world at 10 years old, do you? So, all my friends went to whatever good grammar school they wanted to and I was sent to this particular school.

When I went to university, I found that all of my friends of an African heritage, the same thing had happened to them. We were all sent to the lesser schools and our white friends had a choice, even though they weren’t that good. At 10/11, I realised that no matter how good you were, no matter how able you were, that the system was not fair because you could be discriminated against on whatever basis people want to discriminate on. I wasn’t aware at the time of what I was facing, thank goodness - I would have had a breakdown. I just felt very heavy. I knew that something was very very wrong and at that age you just don’t understand race. I didn’t understand race. I grew up in a white area, I didn’t grow up in an area of mixed ethnicities - all my friends were white, I didn’t think anything of it because they were my friends and it was my culture as well.

NC: And how did your mother react to the situation?

ST: I was so embarrassed that I just got on and went to the school and did what I needed to do but my mother didn’t let it go and she went to the Director of Education for Newham. I didn’t even know about it. And she said that she wants her daughter changed. Well, first of all, she went to the teachers at the local primary school and they said very patronisingly: “There, there, Mrs Thompson, you know that your daughter is no trouble. She won’t cause any trouble and she’ll be perfectly fine at that school.” My mother didn’t leave it there - she went to the Director of Education and said that this is a real injustice and that “my daughter should be sent to the school that she deserves to go to.” I think that led to me in my first year at the secondary school being sent for an interview at one of the good schools and I got into one of the good schools that had a steady stream of people going to Oxford and Cambridge.

NC: And what was the justification for putting you in that less academic school?

ST: There was none. That’s the point. What would they say? “We’re racist and we don’t want your daughter going to a white school”? Well, they said that I would be better off in the school that was I sent to. There was no justification. But you can always cover up injustice if you have enough leverage.

NC: Could you tell me more about your perceptions of representation of women in classical music while you were growing up?

ST: Well, growing up, there wasn’t an awareness in my generation of a lack of women composers or a lack of women musicians. I wasn’t aware of the lack of women in music until I became maybe more politically aware and that was leaving university when I was 21. So, I wasn’t intimidated. I didn’t see any barriers to me becoming anything because I saw women and/or people from all kinds of backgrounds doing what I did, so I wasn’t thinking of limitations.

NC: And what changed when you left university?

ST: Well, I became just more conscious of limitations. I was a founding member of Women in Music where we discussed the lack of opportunities for women in all areas of music. There were certainly very few female composers who were of note or were known when I left university in the 80s, so it was around that time that I became aware of the fact that there was not much exposure or women were not getting as much visible success as their male counterparts. Then, historically, I hadn’t thought that there is no female Bach equivalent, there is no female Beethoven equivalent, there are no women in history that are known in the way like Bach, Beethoven and Brahms, there are none whatsoever. But you just don’t even think about it because the issue is not raised.

I think that women were not perceived as composers. As I said, it’s peer-validation, and women were up until maybe the beginning of the 20th century or maybe even the mid-20th century, were perceived as having to do particular occupations that didn’t include being writers of music or musicians, certainly not writers or authors of music. So, I’m just trying to think of who the first recognised composer was… I mean, women composers were recognized in retrospect - they weren’t recognised in their time. So, retrospectively we are looking at Hildegard and various female composers, Clara Schumann, but this is a very recent phenomenon. I recently made films about a series of women composers, so I know that the BBC and Radio 3 are now very interested, but it’s a recent phenomenon that we are looking at.

NC: And what about the representation of people of colour in classical music? Specifically, what do you think about Black representation in music?

ST: Well, I prefer to say ‘persons of visibly African heritage’ which I believe that I am. I think that representation is being written out of history. I think that persons of visibly African heritage have always been a part of building the classical music repertoire and have just not been acknowledged. So, it’s something that is being written out of western musical history, and that persons like myself are writing in. So, for the BBC for example, I have written an entire timeline, a historical timeline of composers of African descent that have created innovations in classical music but they just haven’t been credited. It is a huge issue.

NC: Do you think that’s changing at the moment?

ST: Not really, no. It is changing because persons like myself are making it an issue but a lot of the way that history has been written has been skewed or has omitted the contribution of persons of African heritage. So, I think, in terms of music, it’s the same thing as when you look at the French Revolution or if you look at World Wars One and Two - everything has been written in a particular way and written out. If you look at the Georgian period, it doesn’t mention that all the mansions that were built during the 16th, 17th, and 18th century were built from the profits made from African persons that were transported to the Americas and the West Indies, and all those profits were what made Britain great. So, it’s a re-write of history which is beginning. It is beginning.

NC: You describe yourself as a cultural activist, what does that mean to you?

ST: Yes, I suppose there came a time when I was at University, when I realised that I wasn’t going to learn anything about the contribution of people of African descent, the contributions they’ve made. Well, I didn’t even know that they made a contribution to classical music at the time. And I became very quite depressed about it because I couldn’t see any representation of myself in what I was learning and I thought there must be.

I remember there were classes on what Debussy was listening to, Chinese music, and then Arabic music, and all the other sort of major cultures. But there was never ever any mentions of the contribution of Africa and its progeny. And having had my experience at the age of 10, I just felt that heavy feeling that there was some kind of injustice there and, at the same time, I was aware in literature of all the contributions that writers from the African progeny were making. So, I thought there must be something comparable in the music I was learning about. But I didn’t have access to it, and even now I am probably one of the few people who are aware of the lack. It doesn’t even dawn on people that there aren’t major female artists in the whole history of art, until the 20th-21st century. People just don’t even question it but I did question it and I think, at the time, I was the only person asking those questions. Because even now I go to major conferences and people aren’t asking those questions and I am asking those questions. So, the questions are just being asked for the past couple of years or so but I’ve been asking them since the 80s.

NC: And how have you attempted to affect this situation and create change? Obviously, there has to be a structural shift and white people need to step up, but what have you been doing on an individual level?

ST: Well, I’ve done it. For me, to achieve what I’ve achieved is extraordinary. Considering that from the age of 10, I was not expected even to get an education, I’ve sort of blown away all those barriers and got around them all. So, I do believe that I’ve been very fortunate to have been able to do what I wanted to do but it’s been about a lot of hard work and determination because there were lots of people telling me that I can’t do it. So, being able to carve for myself that creative space, that’s the extraordinary thing because it’s a nearly impossible thing to do.

NC: And in your project called Heroines of Opera you sought to give more exposure to women who have been unacknowledged in history, such as your 2007 piece called The Woman Who Refused to Dance which you composed for the opening of the Parliamentary exhibition, British Slave Trade: Abolition, Parliament and People - could you tell me more about that and who were the women that you wanted to shed light on?

ST: Yes, as a composer, I was asked to represent that Act of Abolition which was in 1807 I think, yes, because the anniversary in 2007. So, I knew I was going to have a piece performed in Parliament in Westminster Palace and I wanted to represent these 500 years and, well, plus, because we’re in post-enslavement now and we’re barely away from it with the psychology and what’s happening - there’s still so much discrimination.

So, I decided that I would produce something around women because I thought that element was missing in the narrative that is normally told about the trade of enslavement. And I wanted something that unified the trade geographically in some way. So, after much consideration, I chose to feature 3 women from 3 continents involved in the trade. The ships of enslavement came from England and went to Africa and then went to the Americas and then came back to England. So, I decided to choose a woman who was involved in the trade in England, and then a woman who was involved in the trade from Africa, and then a woman who was involved in the trade in the Caribbean or America, or South America for that matter.

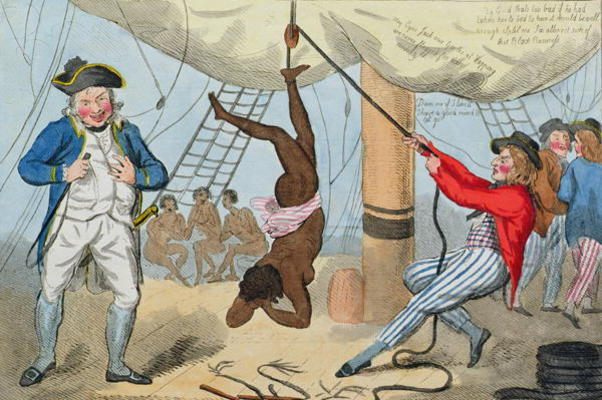

And so, I found 3 women who were involved. It was triggered by a political illustration that I saw, created by Isaac Cruikshank in the late 18th century, when the archivists of Parliament took me down to see artefacts that they had collected from the trade, such as the shackles. I saw shackles and I saw things that they put around people’s necks and all kinds of atrocious things but then they showed me this painting by Isaac Cruikshank and it was of a woman that was being hung. It was a woman from Africa and a man leaning over her and other sailors gawking at her and she didn’t have any clothes on. She was hanging by her ankle, and I’ve never seen anything like that. I thought it was absolutely awful, I was absolutely shattered when I saw that painting and I thought “That’s it, I’ve got to represent this woman who didn’t have a voice,” I called it The Woman Who Refused to Dance and I created an orchestral piece with full symphony orchestra and a singer. That was the beginning of the Heroines of Opera series.

treatment of a young Negro girl of 15 for her virjen (sic) modesty" by Isaac Cruikshank (1792)

NC [ASIDE]: In the painting that Dr Thompson is referencing, a sailor on a slave ship is suspending an African girl by her ankle from a rope, while on the left, a man stands with a whip in his hand. Cruikshank’s painting tells the story of Captain John Kimber, who was accused of brutally assaulting and murdering a teenage slave girl, because she refused to dance on deck.

[audio excerpt of The Woman Who Refused to Dance]

The Woman Who Refused to Dance - Shirley Thompson Music from Tête à Tête on Vimeo.

The other 2 pieces in Dr Thompson’s trilogy feature Queen Nanny of the Maroons - an 18th-century leader of the Windward Maroons, who had escaped the brutality of enslavement and fought a guerrilla war over many years against British authorities in the Colony in Jamaica, and Dido Elizabeth Belle - England’s first aristocrat of African heritage.

NC: And another one of your projects that I find fascinating is the Franklin Effect project which explored the relationship between music and science, could you tell me more about that?

ST: Yes, I got a call from Minerva Scientifica, the company running the project, and it was so exciting for me because, liking all these disciplines of science and so on, it was absolutely ideal. There were 4 leading British female composers matched with 4 leading female scientists in different disciplines of science. The person I was matched with was a genealogist, Chair of Genetics at King’s College. And she is looking into DNA and its effects on how you can use DNA to trace how and when cancer appears in cell replication.

I created music that tried to reimagine her research in cell replication. So, I wrote a piece called ‘Random Sequences’ which looks at the randomness of the DNA when the cell splits and how it can become deformed. And another piece about replication, so I represented it in music and I used musical themes of replication, so repetition. I also used a particular style of music to represent this phenomenon in the DNA.

[audio excerpt of Life Sequence: II. Random Sequences]

NC: I also read that you’ve been involved in educational programmes at schools such as in your area of Newham, could you tell me about it and why you think musical education is important?

ST: I created a big project for Newham called Every Child A Musician, whereby I devised and created a project for 500 schoolchildren in Newham to tell the story of London through music. And that’s a project I ran over 18 months, with children performing instruments, expressing themselves through dance and through visual arts, and we had a performance of this piece called Newham Spectacular, that was a precedent for music education and was seen of such value that the Borough adopted it as something that made them provide musical instruments for all children in Newham schools. That project actually became the foundation for the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympics. So, that’s the power of music as I see it. It’s very powerful.

Going back to my Renaissance ideal, I think that music is a very important part of anybody’s development. It’s good music, learning an instrument, reading music. It’s so good for so many things. When I went to university, my first degree, many of my medical students friends were better musicians than I was. I mean, they could play the violin better, and they just happened to take medicine.

I think that everybody should learn a musical instrument or be able to sing or be able to write. I think it’s a part of that Renaissance ideal or that well-rounded human being ideal that music, dance, sport - I think they are a basic part of being a whole rounded human being.

NC: And which connections do you see between music and leadership?

ST: Well, I think leadership is about character. As a musician, I led my local youth orchestra, I was put into many physically leading roles. As a violinist, you have the potential to lead the orchestra, that’s your title, whereas if I played the trombone, I would not be a leader. If you’re in a string quartet, the violinist is always the leader. So, perhaps because I am a violinist that was put into a leadership position, there is always that concept of leadership.

But I think there are so many things about music that imbue you with strong qualities of leadership, and those are: you need to be very determined; you need to take responsibility; you need to be very particular, very detailed. But discipline, I think, is the number one. Classical musicians are like dancers - very very disciplined. And I think that’s a major attribute.

To gain excellence in an instrument, it takes the hours it takes. My violin teacher, even when he led the English National Opera, he was practising 8 hours a day before he went to work. And that’s the level of discipline that you need to have to make it in the profession, a profession that isn’t particularly well-paid. You have to have all of that dedication and determination to stay at a level in order to just survive as a musician. You’ve go to be really exceptional, in the classical music world anyway. You have to be of a very particular character. It’s not for the faint-hearted.

NC: How do you think people can use music to create change in the world?

ST: I think we create change all the time. I mean, I see musicians and creativity as leading the world. I think we do it all the time. I think people look to artists all the time as leaders. What are they doing, how are they doing it. It’s happening now in this Covid-19 crisis - a lot of artists are coming onto media and describing what they’re doing, what they think. I think that people already look to musicians and particular kinds of musicians as leaders.

One of the things I am really happy about is that when I first came into the field of writing contemporary classical music, as somebody of African descent, it was a music that wasn’t necessarily seen as something that people of African cultures were a part of. So, in that sense, I am glad that I’ve shown how much is possible to use music to tell the stories of Africa and its descendants through classical music and that’s what I’ve been doing, which is a bit of a contradiction to many. But I wanted to use classical music to tell stories about the trade of enslavement, and the Windrush women, and so on.

NC: Finally, what is the bravest thing you’ve ever done?

ST: Every time I put the pen on my paper to write something - you to be brave to do that. To stand up for what you’ve written and to own it. You’ve got to be very brave to be an artist. You have to have the courage to believe in yourself, that what you have to say as a musician is worth saying. So, yes, that’s the bravest thing - to have persisted with creating music at a time when I wasn’t necessarily getting the recognition but to still be brave enough to say that it’s important to do this. I didn’t realise that I was being brave but I felt a responsibility that somebody needed to do it. I suppose it was a responsibility that I felt that I had been given the skills to write orchestral music and I had a gift. It’s a gift and a skill. And I just wanted to use it in the best way possible, and for it to be of use in a way that the books that I read about Africa and its progeny gave me a lot of confidence in cultures that are not normally promoted in a positive way, and I felt like I could do that with classical music.

NC: Thank you so much Dr Thompson for coming on the podcast and speaking to me, it’s been such an honour!

ST: And thank you Nikol, an honour likewise. Thank you.

NC: Check out Dr Thompson’s website, www.shirleythompsonmusic.com, follow her on Twitter @shirleyjtmusic, and subscribe to her YouTube channel - Shirley Thompson Music.

Subscribe to the Good Leader on Spotify, iTunes, and Google Podcasts, and follow the Laidlaw Foundation on Twitter and LinkedIn to find out when we release our new podcast episodes. If you would like to find out more about our programmes visit www.laidlawfoundation.com. You can find all the references, further reading suggestions and the transcript of this episode on the Laidlaw Scholars Network - www.laidlawscholars.network.

Our music is by Broke For Free and Tours.

Thanks for listening.

![[CLOSED] Apply to Become an Advisory Board Member](https://images.zapnito.com/cdn-cgi/image/metadata=copyright,format=auto,quality=95,width=256,height=256,fit=scale-down/https://images.zapnito.com/users/290982/posters/b494a8a5-ced0-489b-9b26-6c4da797bedf_medium.jpeg)

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in