Research Takes Time: Reflections about my Research on Neglected Tropical Diseases

Four years ago, I spent a summer in Tanzania working with primary school students. I was positively overwhelmed by the welcoming arms that greeted me and fellow students to the community. The kindness that we experienced was unforgettable and I enjoy reminiscing about the connections that were formed. During this summer in Tanzania, our work included teaching English to primary school students, whilst joining the high school students in their classes. The most long-lasting impact that I still feel today, are the stories that the local students told us about how they were affected by neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).

My journey to becoming a Laidlaw Scholar started with the search for a research project that excited, challenged, and interested me. On this search one particular project caught my eye: “Lead Optimisation of Pan-Trypanosomatid Inhibitors inspired by nature”. Trypanosomatids, a group of kinetoplastid protozoan parasites1, cause Human African Trypanosomiasis (African sleeping sickness), Chagas disease and leishmaniases2, exactly those neglected tropical diseases that affected the Tanzanian community that I spent a summer with. I knew that this was the research project that I wanted to be a part of. Not only was I able to gain knowledge in a chemistry laboratory about the process of drug design and development, but I was working on a project that I had a personal connection with and was thus highly motivated.

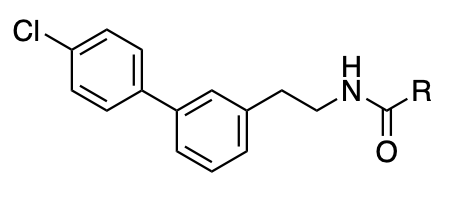

The project itself looked at optimising a chemical compound that was previously found to be active against Trypanosoma brucei. Through variation of a so-called “R-group”, a group which is attached to the rest of the molecule via a carbon or hydrogen atom, the aim is to optimise the activity and selectivity of the compound against T. brucei. In the future, this will hopefully lead to the development of a drug effective against African sleeping sickness.

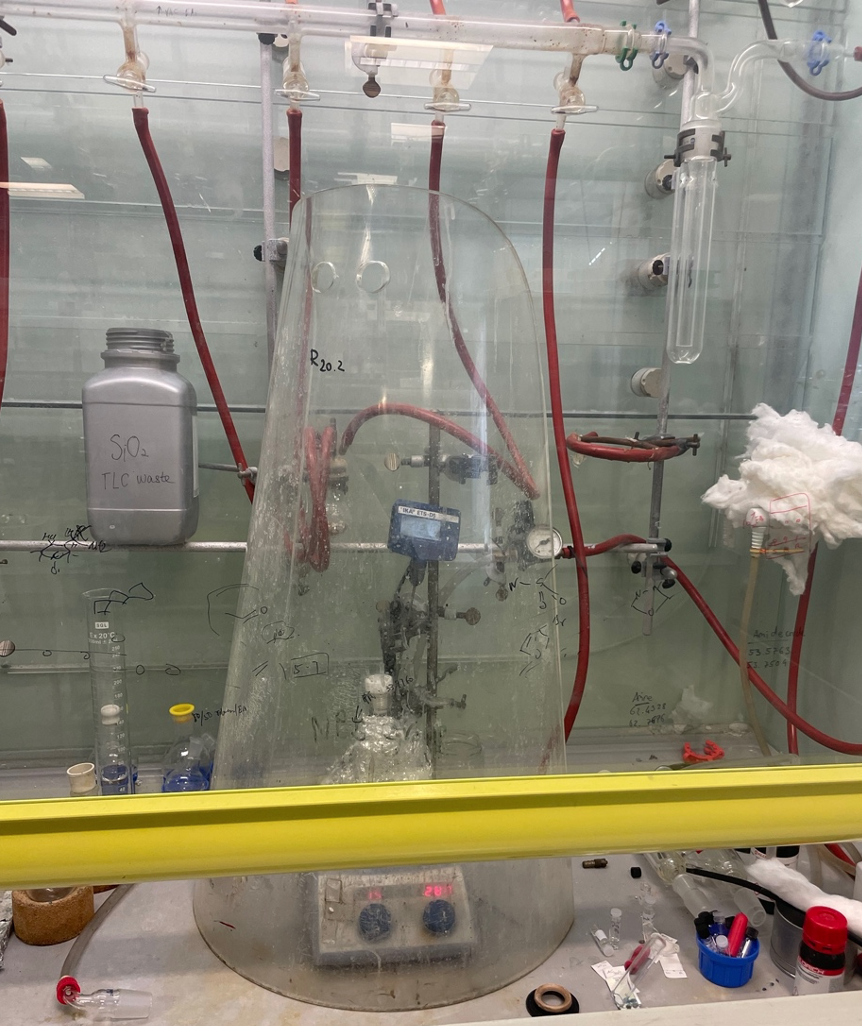

After long hours in the lab, which were filled with many insightful moments, I would return home and think about the work that I had done that day. Some days I had synthesised new compounds, on other days I had purified these newly synthesised compounds and analysed if the reactions and purifications that I had done, led to the desired product. Although, my days were full and I spent at least eight ours in the lab each day, the progress was slow. Research takes time. That was perhaps the most important lesson that I learned. When thinking back to my time in Tanzania and the stories about how family members of the students that I spent a summer with were suffering from neglected tropical diseases, the pace of research that I experienced in the lab was not nearly fast enough. It became increasingly difficult to understand how diseases affecting more than one billion people3 in impoverished communities could be neglected, diseases that cause devastating health consequences, including a variety of social and economic ones3. Although the WHO has developed a new roadmap for 2021-2030 with the aim of a world free of NTDs by 2030, NTDs are still being almost ignored by global funding agencies3.

However, although I felt that the progress was slow, I also saw dedicated researchers; whether these were undergraduate students doing an internship, PhD students, postdocs or professors, they came to work in the lab every day, putting in countless hours to synthesise, purify, test, analyse and re-design numerous compounds with the hope to one-day, develop a drug active against T. brucei. Their creativity, perseverance and enthusiasm made me hopeful. If we continue raising awareness about neglected tropical diseases, so that these become more widely researched and funded, and most importantly no longer neglected, than we give dedicated researchers, like the ones that I had the honour to work with, a chance to reaching the WHO’s goal for 2030 of a world free of NTDs.

Knowing that creative minds with resilience and perseverance were working hard every day, researching NTDs, allowed me to become hopeful again. Yes, research takes time, but if we support our researchers and work collaboratively on a global scale, exchanging our knowledge with one another, then we can speed up the process. Hopefully one day a young aspiring researcher can then travel to Tanzania and hear stories about how medicines against NTDs that were developed through international co-operations, are saving lives in the local community.

I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr Gordon Florence, as well as our Laidlaw cohort leader, Dr. Cassice Last, and my wonderful Laidlaw cohort for their continued support and guidance throughout my research project. I would also like to express my gratitude to Lord Laidlaw and the Laidlaw Foundation for the opportunity to conduct this important work.

1 A. Kaufer, J. Ellis, D. Stark and J. Barratt, Parasites Vectors, 2017, 10, 287.

2 D. Gambino and L. Otero, Front. Chem., 2022, DOI:10.3389/fchem.2021.816266.

3 Neglected tropical diseases, https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and- answers/item/neglected-tropical-diseases, (accessed July 2023).

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in