Reflection 2:

When I first began filming in London, I noticed a pattern—most of my interviewees were young professionals or individuals without children. While their stories were valuable, I realized my documentary lacked the perspective of family units, which are a crucial part of the Hong Kong diaspora experience. Many Hong Kongers who migrated under the BN(O) visa scheme came with their children, navigating schooling, housing, and community-building in entirely new ways. To capture a fuller picture, I had to adjust my approach.

This meant venturing beyond London into the suburbs—places like Milton Keynes, Woking, and Bristol—where many Hong Kong families had settled for more affordable housing and better schools. Logistics became trickier: transportation, accommodation, and scheduling required more flexibility. Thankfully, a few families I interviewed were incredibly generous, offering me a place to stay, which not only eased my budget but also gave me deeper insight into their daily lives.

One of the most fascinating discoveries was how Hong Kongers in the UK formed communities outside of formal "cultural centers." In London, there are established Hong Konger associations and events, but in suburban areas, the connections were more organic. People found belonging in unexpected places:

-

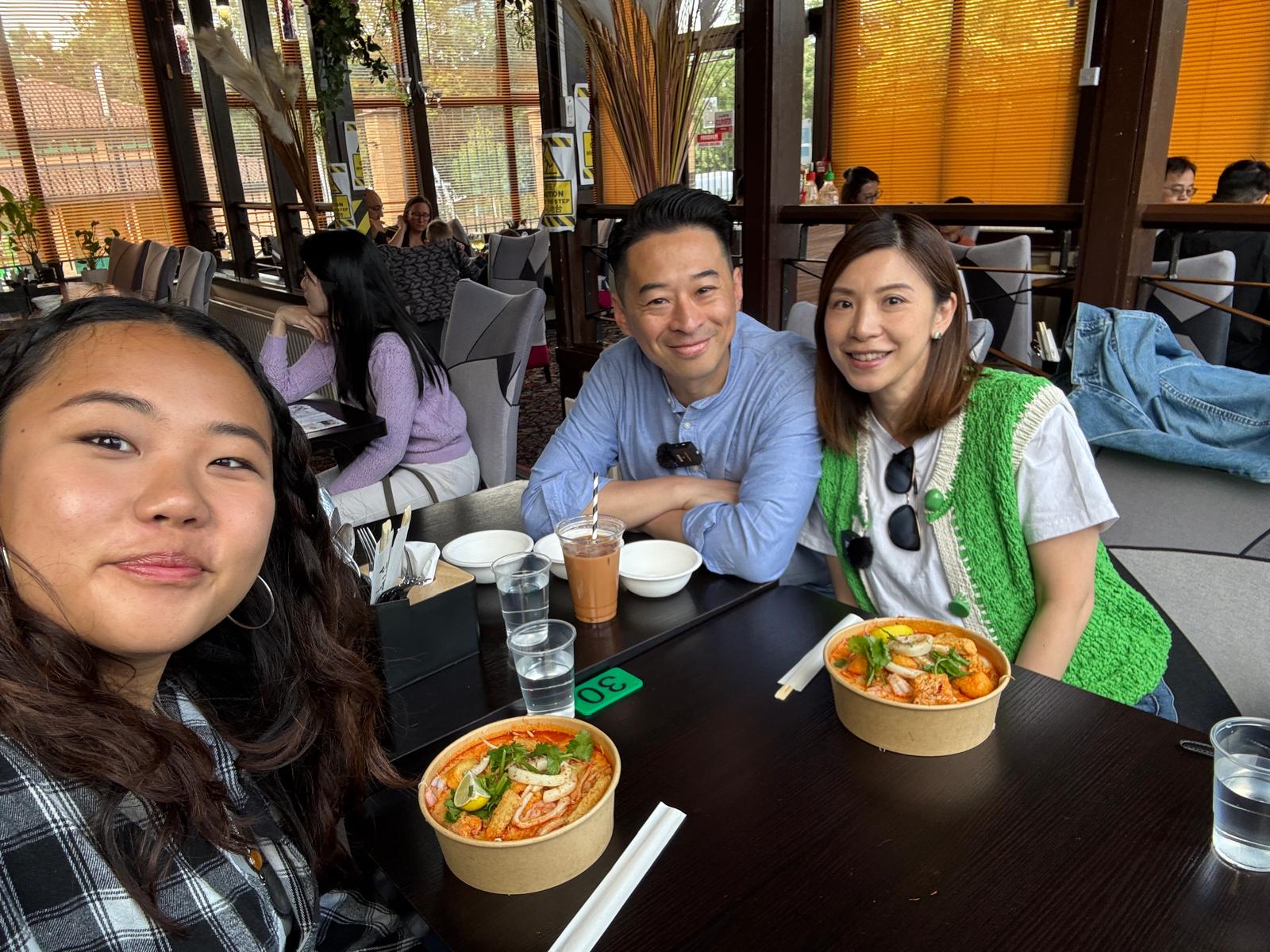

Food Spots: Small Cantonese cafes, bubble tea shops, and grocery stores became informal gathering points. These weren’t just places to eat—they were spaces where people exchanged tips about life in the UK, shared news from back home, and simply enjoyed the familiarity of flavors they grew up with.

-

Hong Konger Basketball Team: A group of Hong Kongers in Milton Keynes organized weekly pickup games. At first glance, it seemed like just a recreational activity, but it was also a way to maintain camaraderie. However, these settings weren’t always conducive to deep conversation—the atmosphere was loud, competitive, and, in many ways, performatively "macho." Talking about emotions or nostalgia was off the table when surrounded by peers. I didn’t get too much interview footage here, but I got wonderful B-roll, and audio clips of Cantonese swearing, which also reminded me of home.

- Backyard Barbeques: More intimate than public meetups, these gatherings were where people, even the basketball crowd, slowly opened up. Over skewers of grilled meat and cans of beer, conversations drifted toward memories of Hong Kong—sometimes wistful, sometimes cautious.

Initially, I assumed that people simply didn’t want to talk about their feelings regarding Hong Kong—especially the men in the basketball group, who deflected personal questions with jokes or changed the subject. But I soon realized it wasn’t that they didn’t want to talk; it was that the setting wasn’t right. When I spoke to them individually, away from the group, their guardedness softened. One man, who had brushed off my questions during a basketball game, later admitted over coffee that he missed the convenience and energy of Hong Kong but didn’t want to appear "weak" in front of his friends. Another, a father of two, confessed that he struggled with guilt over uprooting his children but felt he had no choice. This taught me a crucial lesson about documentary work: people’s willingness to share depends on context. Group dynamics, pride, and even cultural norms around emotional expression can suppress deeper conversations. But given the right environment—private, unhurried, and free from judgment—they often do want to be heard.

What struck me, however, was the hesitation to dwell too much on the past. Many were still in the process of establishing themselves—finding jobs, securing housing, settling their kids into school. Reflecting on "what home means" felt like a luxury when survival in a new country took precedence.

Not every hurdle was emotional or cultural—some were purely logistical. One of my biggest scares came when I had an interview scheduled with a Hong Konger professor in Bristol. We had arranged it weeks in advance, and since I was traveling there specifically for this conversation, I didn’t double-confirm until the day before. When I messaged him, he replied, embarrassed, that he had completely forgotten and was now out of town. If I hadn’t checked, I would have made the trip only to find an empty meeting spot—wasting time, money, and energy. Thankfully, we pivoted and are in the works of scheduling an interview online, but the incident reinforced the importance of last-minute confirmations, especially when dealing with busy interviewees.

This phase of filming was defined by adaptation—shifting locations, adjusting interview techniques, and learning to read between the lines of what people were (and weren’t) saying. The pivot to suburban families added richness to the documentary, revealing struggles and triumphs that urban single migrants didn’t face. The cultural insights reminded me that community isn’t always found in official organizations but in the small, everyday interactions that stitch a diaspora together. Most importantly, I learned that people’s stories aren’t always on the surface. Sometimes, you have to dig—to create the right conditions, ask the right way, and listen not just to words, but to silences. What goes unsaid is often as telling as what is spoken.

As I move forward with this project, I’ll carry these lessons with me: be flexible, be patient, and always, always confirm appointments the day before.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in