Leadership in Action Project: Agroforestry and Education in Madagascar

As a philosophy student, my studies usually focus on the theoretical basis of things, and I typically don’t get many opportunities to implement these values in a more practical way. My research project last summer with the Laidlaw Foundation, where I researched blue-washing in fashion companies, was the first time within the context of my undergraduate education that I was able to take concrete action on environmental issues. I was very grateful for the opportunity to delve into this problem, which I have been interested in for quite some time but could not address very practically in my philosophy studies. Coming off of this experience, I decided that I wanted my Leadership in Action project to have some kind of environmental focus as well.

Since I have had previous experience volunteering abroad, I felt confident that I could find my own independent project that fit my goals and personal criteria. It was very important to me to find an organization that was run by locals and that did not welcome foreign volunteers at the expense of local workers.

After many hours of searching, I found Akiba, a small organization in Madagascar that practices agroforestry on the small island of Nosy Komba. The association uses the profits from their agricultural operations and the small monetary contribution asked of foreign volunteers to fund a primary school with over 100 students, ranging from preschool age to the 6th grade. It also employs over 20 local men and women for the sustainable production and transformation of crops, as well as for construction, teaching, and the everyday management of the association. Additionally, the association buys surplus crops from many local farmers, greatly contributing to the local economy and giving more financial security to the many villagers living under relatively unstable financial conditions.

It took me a few days to find my bearings when I first arrived. Located in the middle of the forest at 500 meters above sea level, it takes an hour to trek up from the small seaside town of Ampangorinana, through dense forest populated by boas, chameleons, and lemurs, and past some rewarding views of the bay. At first, I was most interested in participating in the association’s agricultural projects, as I wanted to learn more about agroforestry. Agroforestry is an eco-friendly cultivation technique where crops are cultivated within the natural forest ecosystem, resulting in crop diversification, healthier soil, habitat protection, and more profitable and productive land use. Akiba produces a huge diversity of crops such as cacao, coffee beans, pepper, jackfruit, vanilla, pineapple, sugar cane, and combava using this method. In my first days, I helped harvest coffee beans, sorted drying vanilla pods, peeled and juiced sugar cane, and helped with other miscellaneous agricultural tasks.

Once the program director found out that I am fluent in English (most people there speak Sakalava, Malagasy, and French), he soon asked me to hold English lessons for students at the primary school as well. For the next two weeks, I held regular English lessons, teaching the preschool and kindergarten-aged children songs in English and playing educational games with the older students to teach them basic vocabulary and grammar. In my second week at Akiba, the oldest class of students passed their end-of-primary-school exams and were invited to a day of snorkeling in a nearby nature reserve by a local tourism company as a reward. To prepare them for this field trip, I and two other volunteers created a lesson and pamphlet explaining the different ecosystems and animals they would encounter, as well as why sustainability is important to protect these fragile systems. I also held a special class for them where we practiced the names of all of the plants and animals they might see in English. On the day of the trip, we first taught them how to stay floating on their stomachs and how to use their mask and snorkel, before swimming off with them to explore the coral reefs of the reserve. Watching the students learn how to swim and snorkel, have fun at the beach, and discover the dazzling local marine life for the first time made this day one of the most rewarding of the six weeks I was at Akiba.

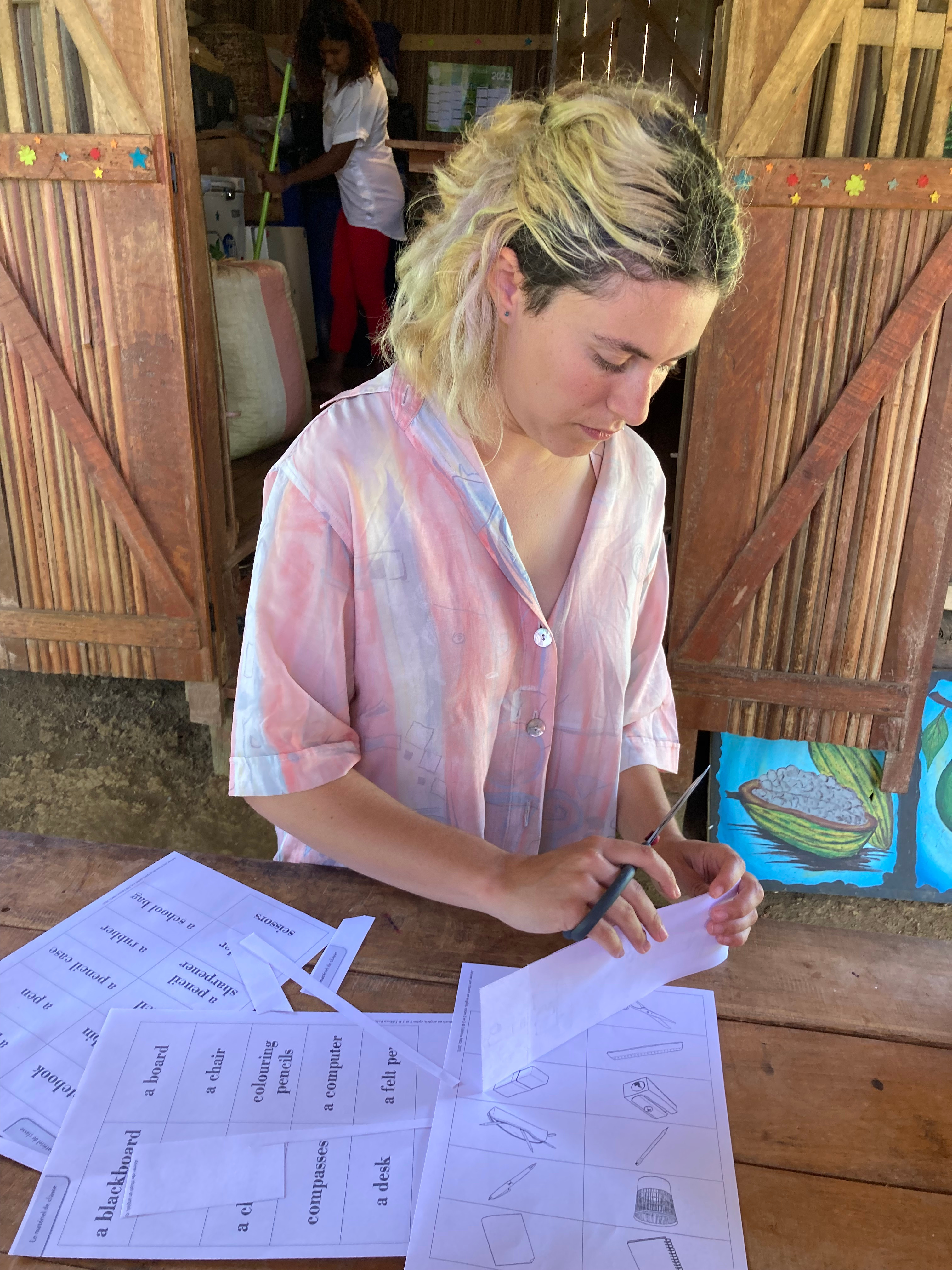

After two weeks I had gotten a better understanding of how the school was run and where I could be most helpful. Since the teachers have either only a rudimentary or no understanding of English, I began to discuss how I could help them better integrate the state-mandated English curriculum into their school day with the school’s director. We came up with a plan for me to elucidate the state curriculum and grammar targets as well as create additional learning tools such as vocabulary cards, games, and voice recordings. Since the school had just been let out for the summer holidays, I spent the next four weeks focussing on creating an attainable curriculum for the next school year that the teachers could feel comfortable teaching, even if they were not confident with their English skills. I wrote and recorded several hours of sample conversations and vocabulary lists, as the director told me that the teachers most struggled with pronunciation. I also wrote several pages explaining basic grammar in simple terms and comparing it to the French equivalents. Additionally, I came up with targeted games that teachers could play with students to further practice the curriculum and sorted these by age group.

When I wasn’t working on the school’s English curriculum, I helped with a few agricultural tasks but mainly worked with Akiba’s construction team. In the six weeks I was there, the team built two new classrooms and renovated the other four classrooms to get them ready for the next school year. I helped put up walls made of ravenala, the quintessential palm from which most structures are made in the region. I also planed down the floorboards in the new preschool classroom and painted all the blackboards and school tables. Working with the construction team was extremely inspiring and fascinating. The team had innovative ways of building the framework of these large classrooms using very limited tools and only local, ecological materials. They were also extremely skillful in handling carpentry tools and climbing precarious bamboo scaffolding, and I learned a great deal about traditional and sustainable building methods from them.

By the end of my stay at Akiba, I felt very fortunate to have lived and worked alongside the people of Nosy Komba for a short time. I learned a lot about traditional Malagasy culture and was left in awe of how ecological and communal this beautiful culture is. I was also very pleased that I was given the opportunity to cultivate my leadership skills by taking the initiative to update the school’s English curriculum. Madagascar is one of the most beautiful and unique countries I have ever had the pleasure of visiting and it was a great privilege to be integrated into the Akiba community. My time in Madagascar was truly inspiring and I am extremely grateful to have had the opportunity to immerse myself in its culture and participate in an ecological and social project.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in