Leadership in Action Blog Summary

Leadership in Action Blog Post

Murphy Bonner

Georgetown University Laidlaw Scholars Programme

Leadership in Action Showcase

August 26, 2025

Acknowledgements:

I want to first thank my Laidlaw Advisor, Dr. Kathleen Guidroz in the Sociology Department at Georgetown University who has been a constant support throughout my entire Laidlaw journey and in my academic career. A special thanks also to the amazing Georgetown University Laidlaw Coordinator Colleen Dougherty. Colleen’s kindness, dedication to the mission of Laidlaw, and work ethic are unparalleled. All of us scholars are so grateful to her for the guidance and support she has offered us throughout the program. I would also like to thank the Laidlaw Scholars Foundation for providing myself and the other scholars with the opportunity to do work that we otherwise never would have had the chance to do and to the Georgetown University Laidlaw Scholars Programme for supporting my research and Leadership in Action project.

Overview:

For my Leadership in Action Project I worked at the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and volunteered with local organizations that provided support services for the unhoused. Together, these two experiences allowed me to serve others in two very distinct but complementary ways: one by way of legal recourse for employment discrimination based on factors like race, age, gender, or sexual orientation and the other through being part of the community and directly interacting with those most vulnerable. This summer I was able to embrace the Laidlaw Scholars Foundation mission of sustainable service and leadership through experiences that pushed me beyond my comfort zone to achieve a greater good. I learned a lot this summer and have catalogued my work in the form of a blog post for each of the weeks in my Leadership in Action journey.

Week 1: Getting Started at the EEOC

In my first week at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) I had quite a bit to learn about the field of labor and employment law. By way of background, the EEOC was established by the US Congress to enforce Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The purpose of the commission broadened as the number of laws that protected individuals from discrimination in the workplace broadened. The scope moved from discrimination based on sex or race to gender, sexuality, age, pregnancy status, and other factors. The mission of the EEOC is to “prevent and remedy unlawful employment discrimination and advance equal opportunity for all.” My first week at the EEOC in the Enforcement Unit was spent mostly reading the intern “primer.” This brought me through all of the different statutes that the EEOC enforces: Equal Pay Act of 1963, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967, Rehabilitation Act of 1973and Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 1992, Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Government EMployee Rights Act of 1991, Notification and Federal Employee Antidiscrimination and Retaliation Act of 2002, Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008, Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, Pregnant Workers Fairness Act of 2022. Along with each statute are the types of evidence that is required in order for the EEOC to file a charge, the requirements for a claim to meet aspects of the statutes, and other important information about the enforcement of these statutes. It was quite a bit to digest and so in order to ensure that I had a handle on these statues my supervisor worked through practice scenarios with me about what law would apply in what case and if the Potential Charging Party (PCP; the person who contacts the EEOC because they believe that they have been discriminated against). I did okay on these questions but there was still quite a bit of nuance that I had yet to understand.

Week 2-3: Shadowing Intake Interviews

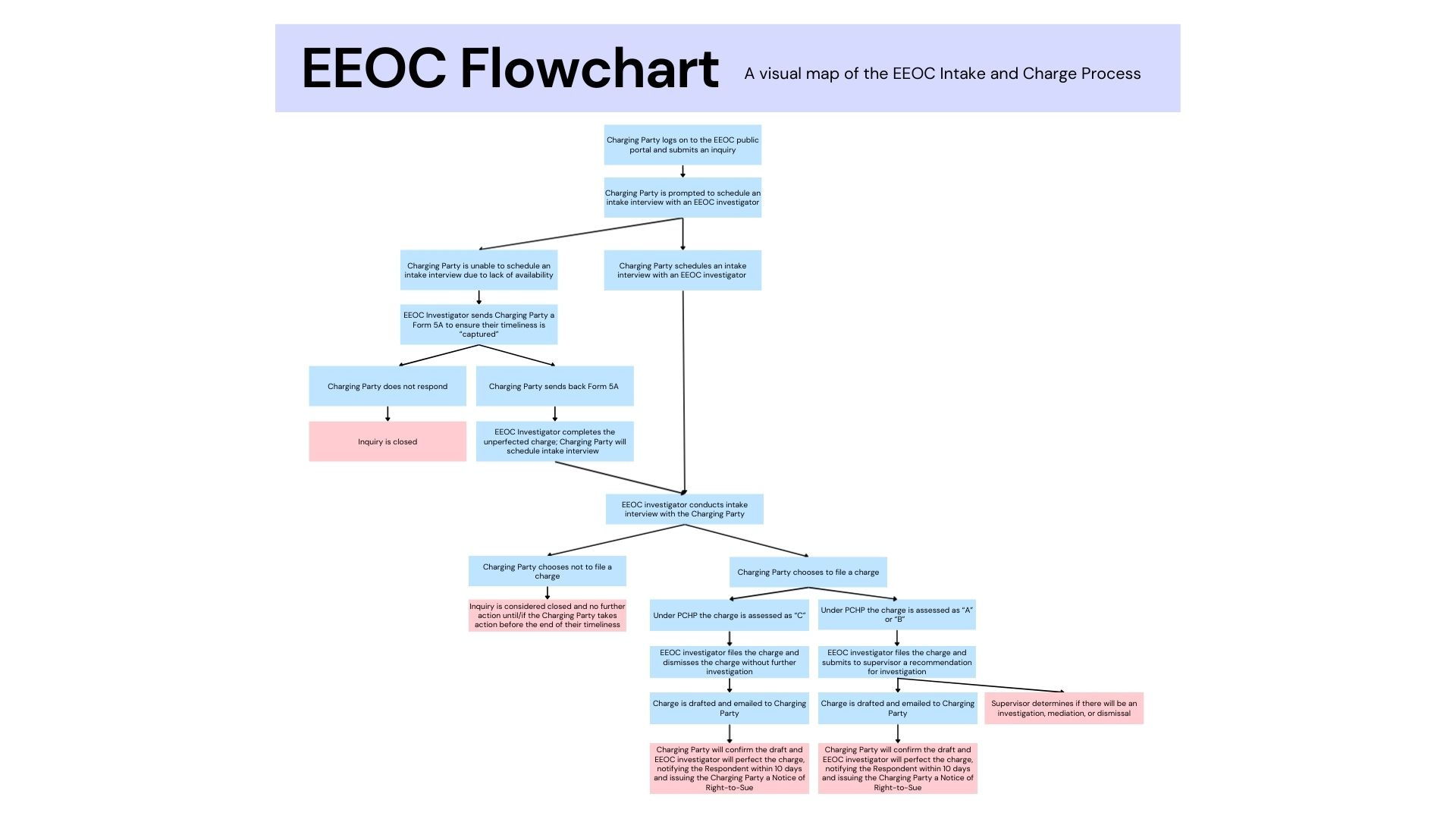

Another part of the background about the EEOC that I had to learn is what they actually ‘do.’ While I knew that they had the power of enforcement of the statutes I learned about previously, I was still unsure of what that enforcement actually looked like. From their creation, “the EEOC has the authority to investigate charges of discrimination against employers who are covered by the law. Our role in an investigation is to fairly and accurately assess the allegations in the charge and then make a finding.” The way that this happens is through the intake process. I have tried to recreate the basic layout of the process that the EEOC undergoes through this flow-chart:

To explain the flow chart, the process begins with an individual who feels they have been the victim of some sort of employment discrimination based on a protected class (i.e. not hired because of their race, religion, sex, gender, etc; fired because of their race, gender, sexual orientation, age etc; not paid fairly or not given a promotion). We call this person a Potential Charging Party (PCP). They are ‘potential’ because not until the EEOC gets involved are they a charging party. The PCP then contacts the EEOC via an online portal to set up an intake interview. The Cleveland Field Office of the EEOC has many more cases that need to be dealt with than investigators able to do all of the intake interviews. Because of this, there is generally a large back-log of cases and I will later learn what the office does in those circumstances to ensure that everyone has the right to tell their story and go through the process. After the EEOC has received the PCP’s information and scheduled an intake interview, the PCP will speak with an EEOC investigator during that interview. This interview gives the PCP to tell their full story, make clear what their claims are, and specify under which statute they are saying there is discrimination. The investigator will ask many questions of the PCP to ensure they have the story completely correct and know all the necessary information in order to make their determination. Thought everyone is guaranteed the right to speak with the EEOC and be given a notice of rights to sue, the EEOC has full discretion on which cases it decides to investigate. At the conclusion of this interview, the investigator will use the EEOC’s Priority Charge Handling Procedure (PCHP) in order to classify the case, determining if the case will be investigated by the commission or if the case will be closed and the individual will be given a notice of rights to sue (NRTS). This notice gives that individual the right to file a claim in federal court against their employee within 90 days of receiving that document. It is in this intake process that I was going to be taking part in and so in order to ensure that I did the best that I could for the people who believed they had been discriminated against, I had to shadow many intake interviews with full time investigators. These cases were very interesting, lengthy, and complicated. However, despite the complexity, the best investigators were able to distill the aspects of the statute they were looking at down to a few questions. In other words, they knew exactly what questions to ask to see if the case had bearing (would be investigated) or not. A note here is that the PCHP classifies cases on an A1, A2, B, C scale with C being a case is dismissed; B being a case needs more information to make a determination; A1 being a strong case for discrimination but unlikely for litigation; A2 being a strong case for discrimination and likely for litigation.

Week 4: My First Intake Interview with a PCP

After two weeks of taking notes, making an outline, and learning as much as I could about all of the statutes that the EEOC enforces, the time had finally come for me to do my own intake interview. I was extremely nervous not only because I understood the weight of these interviews - the people who we were speaking never came to the EEOC because something had gone right; many had been fired from their jobs or were being denied accommodations for their disabilities and this was oftentime their only hope - but also because I knew how unpredictable they could be. In a lot of ways, the only way to truly prepare was to practice them. I was thankful that I had had the chance to learn from so many kind and caring investigators who went out of their way to let individuals be heard and tell their story. They recognized that for many of them, this was the first time they had been fully listened to, the first time that someone dedicated their full attention to the pain or frustration that they were going through. I reminded myself that while I couldn’t guarantee any outcomes in this process - the majority of cases are dismissed at the time of the intake interview and very very few are ever mediated or litigated - I could guarantee that I was going to let the PCP know that I heard them and that I would do my best to explain all parts of the process that they were currently going through. With those reminders in mind and lots of notes and templates, I placed the call. Over an hour later I was finished and a flood of relief washed over me. It had been stressful at times and there was still plenty of work to do now in writing up a charge for the individual, but I felt that I had helped them and that I had done my job to the best of my ability. It was a really amazing experience and it gave me an additional level of respect for the investigators who I had watched navigate extremely complex situations with composure and compassion.

Weeks 5-6: Form 5As and Trying to Retain Statute of Limitations

As I had mentioned earlier in the blog, the statute of limitations is a very big deal for both the EEOC and, most importantly, the PCPs. For most cases of discrimination, the statute of limitations on going to the EEOC and filing a charge is 300 days from the last incident of discrimination. However, in many states it is only 180 days from the last incident of discrimination. The reason this count is important is because there are many people who cannot schedule intake interviews when at the time of portal which means they are at risk of not being able to speak with an investigator and ‘lock in’ their statute of limitations. However, when the PCP fills out their initial information in the online portal they provide the last date of discrimination which allows the EEOC to see when their last day to file a charge would be. With this information, the EEOC has created a form called a form 5A which allows an investigator to create an “unperfected charge.” This form can be sent to individuals who are nearing their last day to file a charge but are unable to schedule an intake interview because of a lack of availability. This form allows them to write out their story and send it to an investigator. The purpose of this form is that by filing the unperfected charge, the PCP has “locked in” their statute of limitations because they have begun the charging process. With that, the PCP can then schedule an intake interview with an EEOC investigator at the next available time so that way the investigator can “perfect” the charge by using the PCHP. Part of my work was learning how to process and read these forms so in the future investigators can use them before their interviews. In some cases, we would have to redirect the form to a different office because it had been filled out in Spanish. This didn’t mean that the form was disregarded, rather that an office with Spanish speakers would go on to handle the case and the form 5A. There are times when the process of identifying the individuals who are closest to losing their right to file a charge must be done manually by going through the portal and looking at each individual. This work was part of my internship and while tedious, was very important because it ensured that we made every possible effort to allow an individual to exercise their right of filing a charge of discrimination against their employer. Additionally, I knew that I was taking some work off of the plates of an extremely busy workforce of civil servants who had their budgets cut and integrity questioned by the very office that commissioned them.

Weeks 7-8 : Work at Safe Harbor Emergency Housing and Support Services and Georgetown Ministry Center Drop-In

An additional part of my leadership in action summer was to volunteer at food distribution and drop in centers for the unhoused. This aspect of my summer aligned both with the mission of the Laidlaw Foundation and also with my personal beliefs. I have been so beyond fortunate to be where I am and to receive all of the help that I have received it is imperative that I give my time toward the betterment of others in the Jesuit spirit of people for and with others. At Safe Harbor in West Chester PA I had the chance to volunteer with the men’s services. Safe Harbor is the only support service in West Chester PA that provides men and women food, a bed, and a locker to be used during the day. Before I volunteered, I had assumed that a bed was the biggest benefit for individuals there but I soon found out the importance of having a locker to store things in during the day without worry. Many of the men who came in for food and/or a meal had full time jobs but were still poverty-stricken. Having a place to leave their things while at work not only allowed them to do their jobs better, but provided a piece of mind I had not anticipated. At the Georgetown Ministry Center (GMC) Drop-In, I saw how different homelessness looked in an urban environment compared to the more homogenous suburb of West Chester. It is impossible to characterize the group who I had the opportunity to serve while there because they all had come to it from so many different avenues. Some were struggling with alcohol and drug abuse, others with mental health struggles, others with disability, others with family troubles or a recently lost job, and even more with combinations of all of those. GMC not only provided basic necessities like food, water, coffee, snacks, headphones, clothes, support services, etc, but also provided a sense of normalcy and dignity by washing the clothes of guests and allowing them to shower. While not in the drop-in center and walking around DC doing outreach with GMC, I saw how on top of all of the physical struggles many were undergoing, they also had the mental struggle of feeling like ‘everyone was looking at them.’ This constant othering is a burden that many of us do not recognize, I know I didn’t, and by allowing guests to become clean and wear clean clothes it gives them an opportunity to exist in a more ‘normal’ way. In all of these environments I was surrounded by social workers and volunteers who dedicated so much time, in some cases their entire lives, to the betterment of their community and the alleviation of suffering. Their commitment and drive and open hearts were such inspiration and I am so glad to have been able to work with them. Additionally, with each guest that I saw I witnessed a fight in them to keep going even when it seemed insurmountable from the outside.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in