How to Innovate, Responsibly: Redefining Agri-Food Systems for a Sustainable Future by Taryn Chung

The Seed of Curiosity: Discovering the Concept of Responsible Innovation

My fascination with the concept of “responsible innovation” began when I was just ten years old, although I lacked the language or knowledge to realize it. The summer before fifth grade, I serendipitously took a “vertical farming” class, igniting a lifelong passion for environmental sustainability. I was captivated by the idea that technology had the potential to improve planetary and societal well-being, not by completely overhauling current economic and social systems but by improving them. Over time, I realized that prevailing narratives present environmental, social, and economic objectives as conflicting. Nevertheless, with the right frameworks and initiatives, innovations can be developed to prioritize all three simultaneously.

Project "Wild Futures": Approaching the Concern of Future Food Availability

In the spring of 2023, I joined the Food Systems and Global Change “Wild Futures” project led by Daniel Mason-D’Croz and assisted by Cody Kugler. The Wild Futures project aimed to “develop tools to inform food policy to harness the power of innovation while also building in rail guards to avoid their worst unintended consequences.” By researching future food and agricultural technologies and systemic innovation, Wild Futures contributed to the use of the philosophy of responsible innovation development and implementation as a way to expand and improve current agri-food systems to feed a rapidly growing human population within planetary boundaries, varying social contexts, and global economic and political priorities.

By 2050, the human population is projected to reach 9.8 billion. Labor reorganization, depleting natural resources, migration, and other social and environmental challenges exacerbated by climate change will lead to many pressing concerns that, while they may not be new to society, at the scale and magnitude required, will confront leadership and trust. Though our current agri-food system already has enough food to feed this future population of ten billion, supply chain infrastructure and systemic injustices drive food inequity. In a paradox of our world, malnutrition and food insecurity coexist with excessive consumption and preventable waste. To remedy the agri-food system to feed future generations adequately, many believe a new approach must be taken to food and agriculture production and distribution. Society is on the precipice of, arguably already in, “Agriculture 4.0,” or the fourth agricultural revolution, where emerging innovations will heavily influence and change agriculture production.

“IFSS” Portal: the Anatomy of an Innovation

Most of my work during the spring into the summer concerned researching, summarizing, and cataloging these emerging technologies; without fully understanding the implications of my work, I had begun to lay the foundation for “responsible innovation” theorization. Given an “innovation,” such as “plant molecular farming,” “regulations on ESG investing,” and “carbon credits to drive regenerative agriculture,” I would conduct a systematic literature review on the topic and then execute a formatted write-up of my findings for an online portal on food systems innovations. The Innovative Food Systems Solution (IFSS) portal is led by a consortium of organizations and sustained through collaboration with individuals to create an accessible online database of emerging agri-food systems innovations that could help in global initiatives, national policymaking, community investments, personal use, and knowledge democratization.

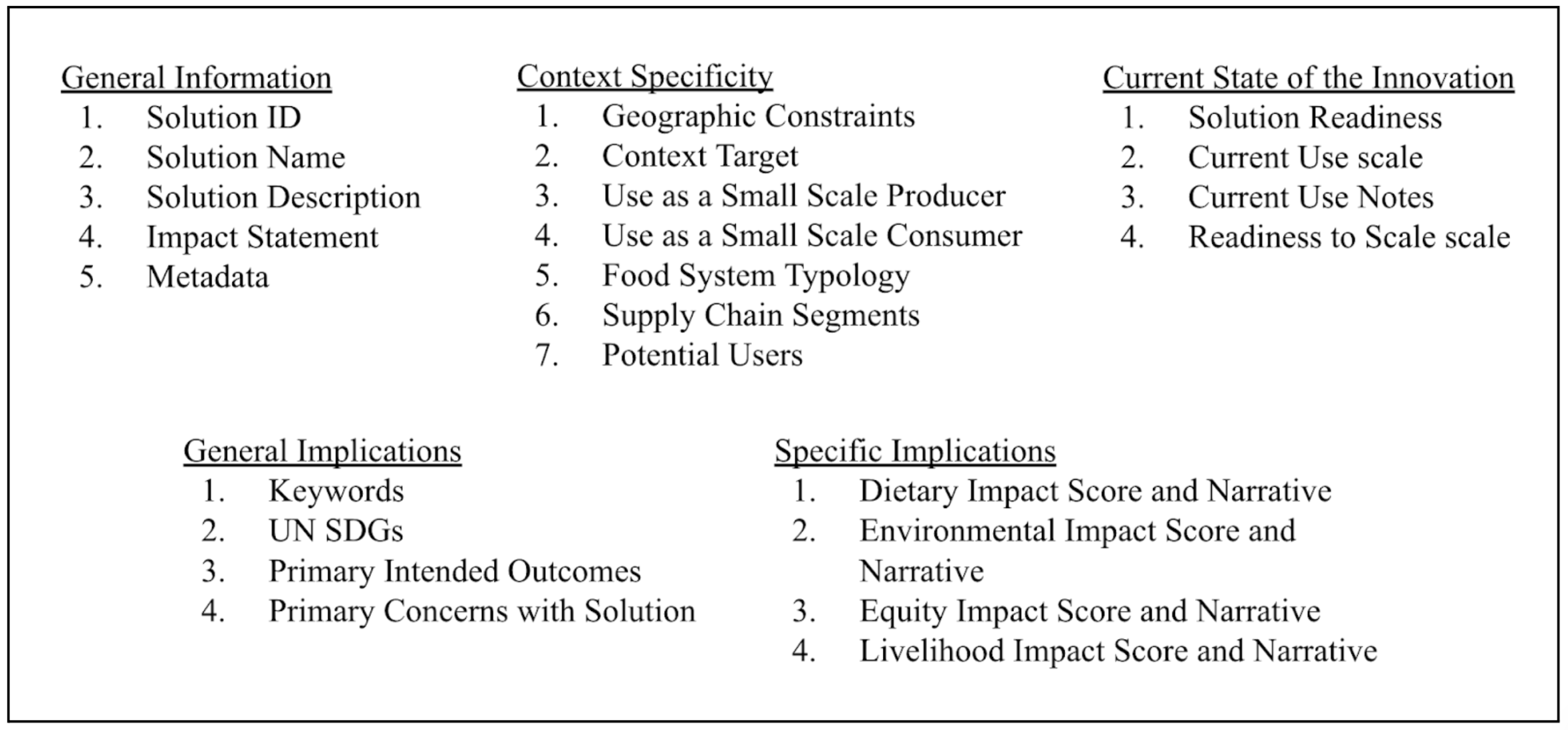

I began my research by looking into the Scopus, Google Scholar, and Google databases for general reviews and specific studies on the innovation in recent years. Next, I reviewed the papers and took notes on information pertaining to a wide audience. Then, I condensed this information into a format that would allow the IFSS team to input it into their online portal. Each innovation write-up comprised multiple sections necessary for a holistic view of the innovation for a wide range of applications. The sections could be categorized into: general information and metadata, context specificity, the current state of the innovation, general implications, and specific implications (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A visual representation of the information in an innovation write-up for the IFSS portal broken into subcategories to illustrate form dynamics.

Complex Relationships: Revealing Systemic Patterns and Interlinked Implications

I was the lead researcher in twelve innovation write-ups and the secondary researcher for two innovations. As the secondary researcher, I reviewed the work done by the primary researcher. Additionally, I had to backfill the inventory for partially written innovations. I helped backfill 24 innovations.

The innovation research process of database scraping, scientific paper review, and formatted write-ups helped hone my technical reading and writing abilities. I enjoyed the standardized process that employed my analytical and communication skills but with constantly changing topics. The research helped me see the systemic patterns (e.g., the quality of water obtained from rainwater harvesting is highly dependent on surrounding infrastructure; the likelihood of being in a community with unregulated industrial pollution is directly proportional to socioeconomic status, and thus, class and race/ethnicity/nationality), linked implications (e.g., improving digital voice technologies for rural farmers would support women’s rights by minimizing time constraints, knowledge limitations, and social barriers), and complex relationships (e.g., desalinating seawater would help alleviate pressures on dwindling freshwater supplies, but making the technology more energy efficient must develop alongside the renewable energy sector for this to be a viable pathway ) between the innovations. One innovation will not change agri-food systems, nor will employing all of them. Every innovation will have positive and negative externalities that will seemingly have to be amplified or remedied by another innovation with different implications. To alter agri-food systems to emphasize workers’ rights, food availability, environmental sustainability, and economic equity, innovations must be considered holistic systems with varying degrees of contextual impact.

Defining the Boundaries of Innovation: Navigating the Broad Concept of "Innovation"

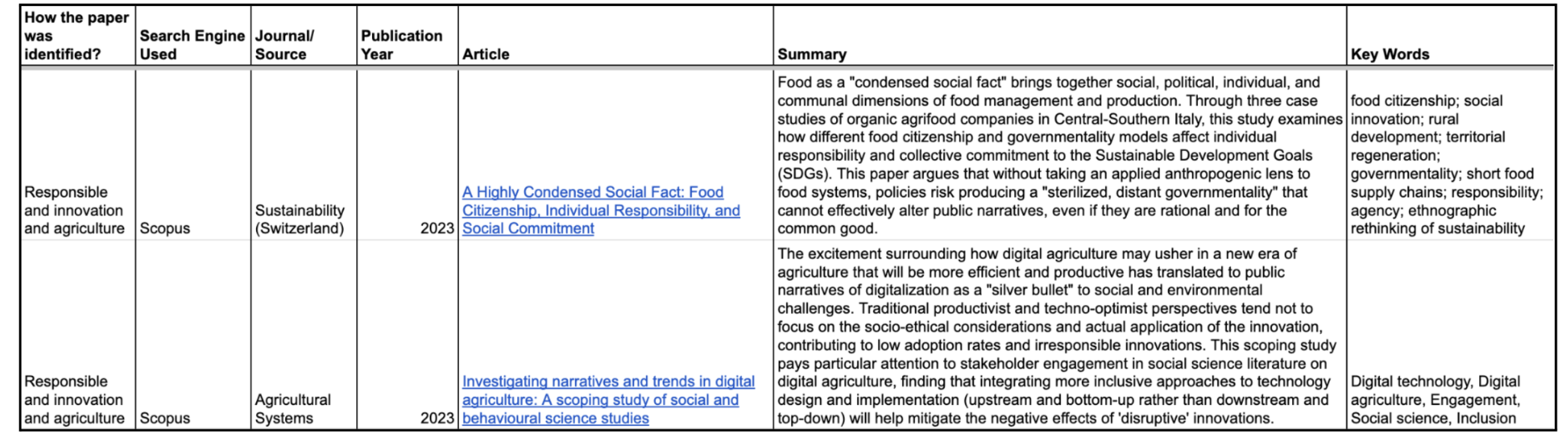

The definition of “innovation” is broad; “responsible innovation” is even more elusive and difficult to define precisely. Throughout the summer of 2023, the focus of my work transitioned from singular innovation research to reviewing the overall concept of “responsible innovation.” I was tasked with developing an annotated bibliography on “responsible innovation” to assist the team in a chapter they were writing on the topic. Each paper included in the annotated bibliography had a section on “How the paper was identified?,” “Search Engine Used,” “Journal/Source,” “Publication Year,” “Keywords,” and, what took the majority of my effort, a “Summary” paragraph (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Two examples of the literature review conducted for the “responsible innovation” annotated bibliography.

Initially, the literature reviewed for the annotated bibliography was referred to me by the lead researchers or self-discovered using explicitly related keywords on the database Scopus (i.e., “responsible AND innovation AND agriculture”). I reviewed 25 papers and presented my preliminary findings to my research group. The main approaches to innovation research were “techno-centric” and “social-centric,” with the concept of responsible innovation falling somewhere between the two. My primary conclusion was that, despite the depth of scientific research on the topic, there would be no agreement on the pathway a responsible innovation must take. The elusiveness arises from the necessity that an innovation must be contextualized to bear accountability. Achieving a universal definition of "responsible innovation" might not only be an unattainable objective but would also deter efforts to and focus away from actual applications of responsible innovation.

This ambiguity does not mean that responsible innovations can not be achieved. To actively combat new technologies and structures being unsustainably forced upon users by developers, users have/will need to become more involved in the development process. Wild Futures' work with the IFSS portal is a great example of community involvement in research because public knowledge can empower communities to take the initiative in research rather than be passive actors in the innovation process. However, it must be noted that there are always temporal and spatial privileges and barriers to consider in an individual’s ability to participate in the innovation process.

Towards a Flourishing Future: Fostering Responsible Innovation for Sustainable Agri-Food Systems

As my knowledge of the “responsible innovation” field increased through readings and talking with professionals in the field, my annotated bibliography took on new dimensions. I began to use more specific search terms that were a niche, subsection, or in a tangential field to the topic, allowing me to develop a greater understanding of the area of knowledge (i.e., “degrowth” and “frugal innovation.”) In total, I included 76 articles in my annotated bibliography.

“Degrowth” and “Frugal Innovation” literature introduced approaches that countered the prominent technology development perspective. These theories propose that improving the food system can be actualized by utilizing or reducing pre-existing technologies to simplify complex situations. Often the implementation of these theories are rooted in the principle of “less is more,” challenging the nearsightedness of merely increasing the volume of output and modernizing technology to improve agri-food systems.

Though it may not seem as alluring as modern startup culture and technological development labs, helping a community through the implementation of innovations should emphasize local, easily accessible solutions. Innovating responsibly may be a simple, humble process for some and will look different in another context, but I would identify it by its greater concern for community and environmental impact rather than headlines or corporate interests. By systemically assessing context-based development, implementation, and maintenance that considers individual requirements, local culture, environmental considerations, social progress, and economic sustainability, technologies evolve from “innovation” to “responsible innovation.”

Conclusion: Integrating Innovation and Responsibility

The broad nature of responsible innovations is its strength. For a new technology or process to be introduced to a community or ecosystem, adaptation methods and reception is crucial to the vitality and sustainability of the innovation. The time, resources, and effort needed for massive change should be selectively used for innovations that a community wants or needs and has long-term potential. Otherwise, in the best-case scenario, resources are wasted; in the worst-case scenario, more damage is done than previously established. However, the concept of trade-offs must be introduced into this rudimentary argument, which goes beyond the breadth of this paper.

Leading narratives in transforming the globalized agri-food system argue for a complete technological overhaul, while others advocate for the abstinence of more development. Most of these accompanying, contradicting, tangentially related, and unrelated studies discuss responsible innovation in some capacity. There can be no “one” pathway to responsible innovation because innovating responsibly must be an active, ever-changing relationship between the literal or metaphysical innovation, the developer, the user, the environment, the various levels of the community, and time. In a dominating neoliberal capitalist economy, time is the most valuable commodity. While I believe that responsible innovations can and should be developed in our current culture, it is crucial we pave the way for a paradigm shift in the way we understand timeframes and lifespans so that immediate remedies, long-term sustainability, and their changing interactions are harmonized.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in