Creating and Teaching STEM Activities in Nepal

This summer, I spent six fulfilling weeks in Kathmandu, Nepal, volunteering for Nepali nonprofit Karkhana Samuha. At Karkhana Samuha, I created hands-on science, math, and computer science lessons for students in grades 6-10. I also taught at Makerspace programs in local public schools twice a week, where I tested and refined the activities we created. I worked on 10 new STEM activities, spent 10 days in schools, and taught roughly 100 different students.

I worked with Surya and Hasin from Karkhana Samuha to create educational materials, and the largest challenge we faced was designing activities that aligned with Nepali educational standards, taught concepts in an engaging way, and only required teachers to use materials already available to them -- all at the same time. We made sure to design activities that worked in the Nepali school environment, which we accomplished by working directly with educators and students to test the materials. Before I arrived, Surya had talked to local educators to hear about what their students were having difficulty understanding. We worked to create activities that addressed those concepts, and then tested them in classrooms, adapting them after each use.

The making space at Niten Memorial School

Every class, I was energized by the curious, caring, and creative students I had the opportunity to teach. On Thursdays, I spent the day with a STEM teacher, Buddha sir, at Niten Memorial School (NIMS). One day, the plan was for me to watch him teach his 5th grade science class, then we would teach two classes in the Makerspace on hands-on engineering and coding with Scratch. I sat down in the 5th grade class and prepared to listen to a lecture reviewing invertebrates. However, a few minutes into the class, Buddha sir decided that his students already understood the required information, and said “Let’s do something different. Duncan is going to teach the rest of the class.” Oh no. I wasn’t prepared for this.

As Buddha sir motioned me towards the front of the classroom, he said that I could lecture about any science topic I want. After fumbling with signing into Google Drive for a few minutes, I pulled up a presentation on potential and kinetic energy that I use with 5th grade students at summer educational programs run by my nonprofit, BX Coding. The rest of the class went by in a blur, as I talked about the different forms of energy, asked conceptual questions of the students, and supported students in calculating the change in potential energy of a pen that I dropped onto a table.

At one point, I asked the students if any of them could explain the concept of mass to the class. A girl in the second to last row raised her hand and I called on her. She stood up and gave the perfect definition and explanation of mass. I lauded her answer and began to turn back towards the board to continue writing the formula for calculating potential energy. At that moment, I remembered what I’d seen other Nepali teachers do after a student gave a great answer: they’d instruct the class to clap for the student’s good work. I turned back to the class, asked them to clap for their classmate, and started clapping myself. The class erupted into applause, and a big smile appeared on her face as the student sat back down. In that moment, I saw the power of silent observation. By spending many days watching fantastic Nepali educators teach their students, I learned the appropriate way to celebrate a student for their good work -- a way that I’d rarely witnessed in classrooms in my part of the United States.

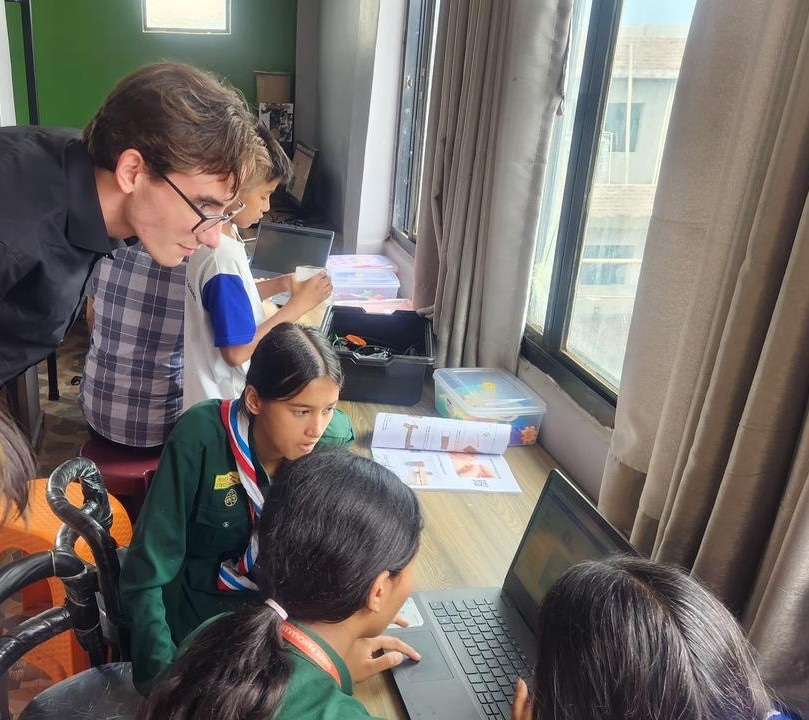

Teaching Scratch at Shree Panchakanya Secondary School

My most important takeaway from my time in Nepal wasn’t an activity I participated in, something I learned, or a skill I built. It was how to treat others. Wherever I went, people treated each other like family.

A few weeks into my time in Nepal, one of the early employees who had worked at Karkhana Samuha for several years, Sangden, was leaving to start her master’s degree in the US. To celebrate her, the entire organization went on a day-long retreat. We spent the day eating, hiking, and cherishing the work that Sangden accomplished. When she flew out, several of her coworkers went to the airport with her on a Saturday evening to wish her goodbye.

The folks at Karkhana Samuha really cared about each other. Beyond eating lunch together every day, they commonly went to dinner after work and attended festivals with their coworkers. They extended this level of care to me even though I was only there for a bit over a month. Hasin picked me up from the airport, Mohit took me on an early-morning walk through his neighborhood, and Sachet took me to a temple and hosted me for dinner at his home. I will forever treasure the time I spent talking, laughing, and eating dal bhat with everyone in the Karkhana Samuha family. I owe special thanks to Hasin Shakya, Surya Gyawali, Sachet Manandhar, and Mohit Maharjan from Karkhana Samuha for supporting me and inviting me into their homes, communities, and festivals.

Karkhana Samuha Retreat Celebrating Sangden

I’ve learned so much over the past two fulfilling and impactful years in the Laidlaw Scholars program. Thank you to Andrew Singleton, Professor Ethan Danahy, the Tufts University Center for Engineering Education and Outreach, the Tufts University Laidlaw Scholars program, and the Laidlaw Foundation for their support and guidance through this entire journey.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in