Co-conceiving sport equipment in public spaces with teenagers: an example that architecture is not a field limited to architects

As part of my Learning-in-Action internship, I spent 6 weeks with the TEPOP association, which stands for “territory fueled by people’s energy”. The association's name profoundly reflects its convictions that certain territories harbor great potential, essentially carried by the people who live there, and that this potential can be activated by collaborating with its occupants. This strong social conviction has resulted in a series of projects, based on participatory architecture, taking place in disadvantaged neighborhoods in Paris suburbs. The collaborative approach, which links architects and citizens in the design process, focuses on young people and the desire to involve them in shaping their own environment. In addition to addressing the highly visible spatial disparities in Paris suburbs, the association also wishes to highlight the lack of sports facilities in these suburbs compared to other areas, despite the fact that this is an important element of social life in these types ofneighborhoods. In this way, the theme of sport is at the heart of all the association's projects, which seek to reflect on habitual ways of practicing sport and propose alternative solutions. The workshops are an opportunity for young people to analyze their own environment and develop a critical opinion of the practices that take place there. In addition, collaboration with architects facilitates the transmission of design tools to young people. These tools enable teenagers to develop their ideas and make their own architectural proposals.

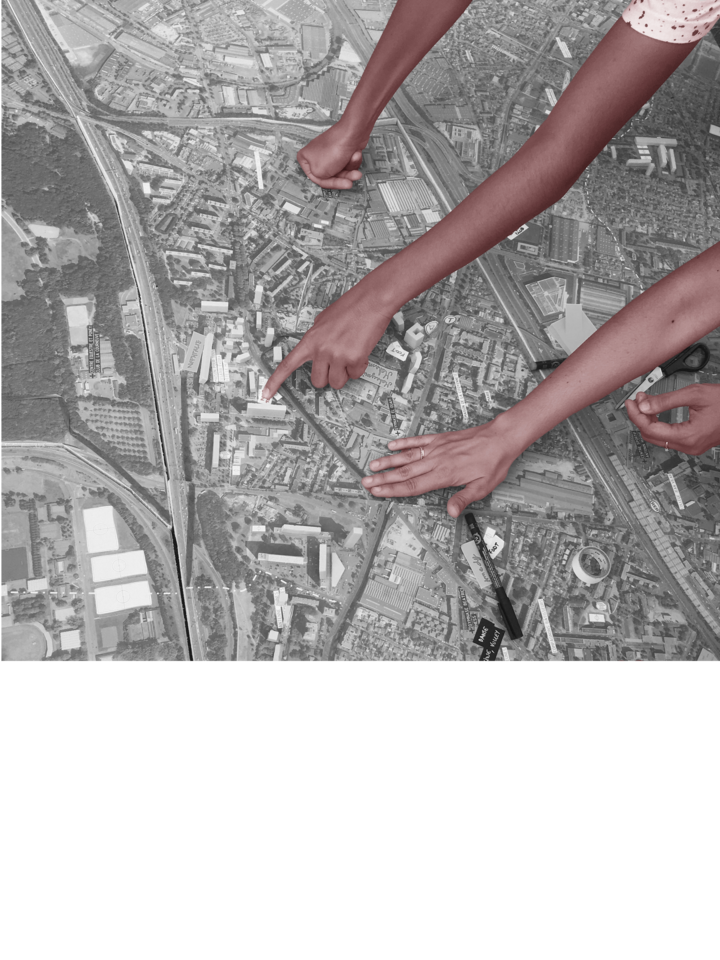

During the summer I mainly worked on a project called “Olympics fueled by people’s energy”. This collective project began in La Courneuve in 2021 with a group of teenagers from La Jeunesse Youri Gagarine (Maison Pour Tous Youri Gagarine), supervised by their supervisors and a team of architects and architecture students. The aim was to co-design a leisure and sport area. After an initial phase of territorial analysis and understanding of the community's specific needs and desires, a first, project was proposed. However, the project could not be implemented. Despite this initial disappointment the project team was able to bounce back. Seizing the opportunity represented by the 2024 Paris Olympic Games, bringing the issue of sport forward and initiating territorial transformations in Seine-Saint-Denis, the TEPOP team and the project participants came up with a new idea: designing a dismountable mobile kit.This is how the Youri KIT was born. Trying to propose a new way of occupying public space, around the theme of competition and sports games, which would break away from conventional sports games, the young people came up with a set of structures, made of steel tubes and knots. But they didn't just create a structure, they also defined original rules regulating its use, setting out a new way of looking at the practice of sport in public spaces. The Olympics took place over the months of May, June and July at various sites around Courneuve. These various events were an opportunity to showcase the work carried out since 2021, and also to invite other young people to share in the fruits of the labors of those who have collaborated with the association.

This introduction to participatory architecture is an innovative approach that differs from the traditional design process taught at school. My role during these 6 weeks was mainly to supervise and assist the group of teenagers who participated to the workshops, and to prepare materials to help them present their work. Unlike the role of the architect that is generally valued, that of the main actor in the project, my role was auxiliary. I had to learn that even if my role wasn't central, it was valuable. That my skills should not be used to place my work above that of others, but to complement it. That I had to value skills other than design, such as facilitating links between local actors and citizens, understanding the links between people and their environment, and making the most of existing ideas and potentials. Finally, that being an architect, and a leader, is not about directing, but about mediating.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in