Arriving with Questions - Reflection 1

I arrived at the site of my Laidlaw Leadership-in-Action project in Amman, Jordan with big questions. Jordan was not new to me, I had been living there for four months prior studying in an intensive Arabic program and living with a host family. Though my status as a cultural newcomer had somewhat subsided by summertime, I was eager to prove myself at my new summer job where I would complete my Laidlaw project. Taxiing to work on my first day, I wondered how I would fit in among my Jordanian coworkers, understanding that my new workplace was unlikely to employ many foreigners. I would be working at one of the oldest and largest nonprofit and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Jordan specializing in grassroots and community-centered human development. I was hosted by the department of gender and female empowerment, joining a team of nine gender-focused staff who would become dear friends.

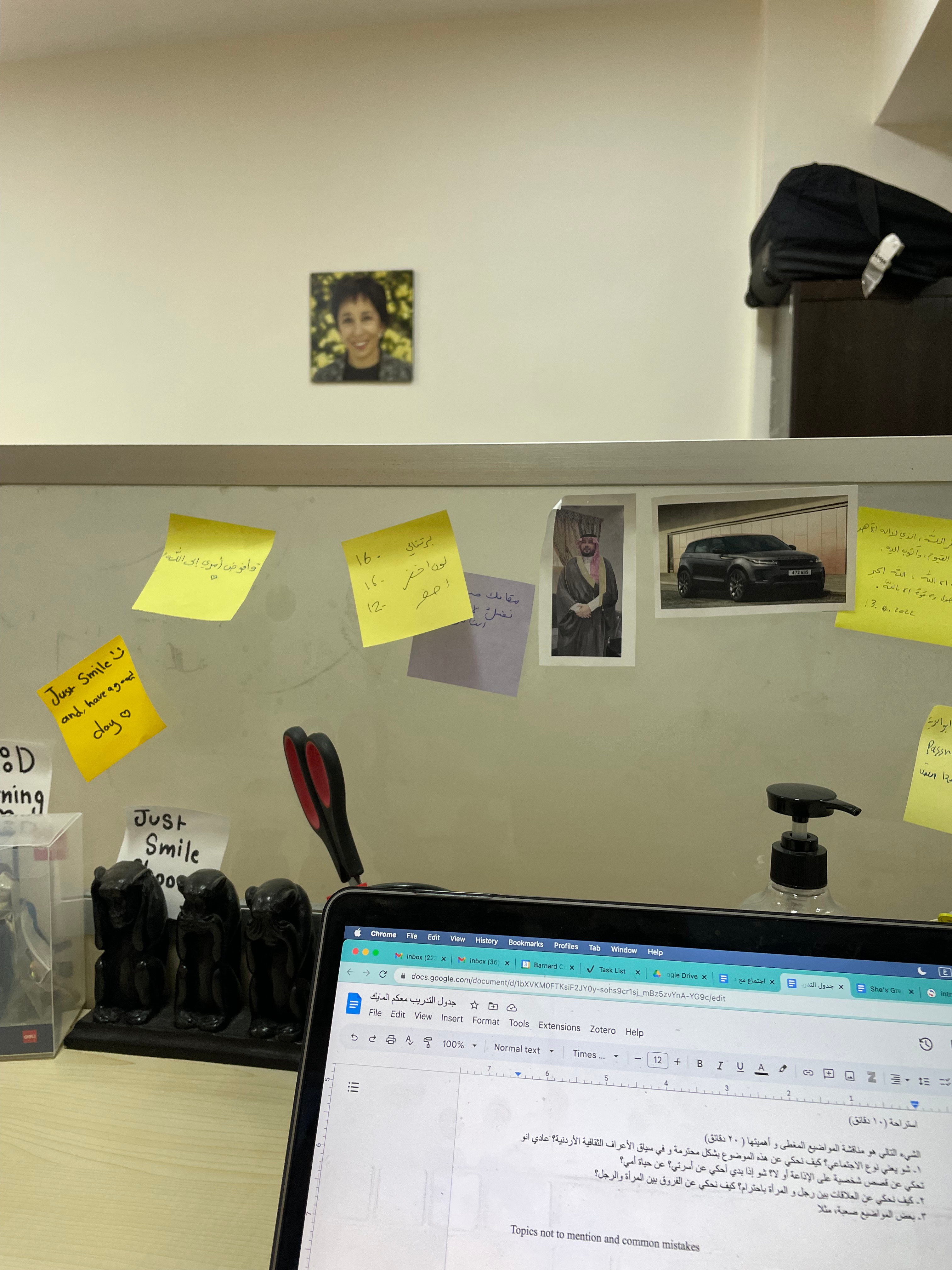

I was welcomed into the small side room home to the gender empowerment department on my first day and offered temporary residence at my absent coworker’s desk: a "musical desk" politics that would soon feel commonplace, immediately orienting me to the beautiful yet perpetually-under-resourced life of an NGO employee. In the first hour I slowly realized that my coworkers were not simply being kind by honoring my desire to practice speaking Arabic, in reality most spoke little English, including my direct supervisor. Taking the linguistic challenge in stride, I resolved myself to make up for what I lacked in Arabic office lingo with interested body language, eye contact, and a quick smile. My efforts were rewarded when my supervisor treated me to a falafel sandwich lunch from the local dukan (store). I would learn in time the important politics of office food and shay (tea) sharing of which falafel sandwiches are a crucial part. I chatted with my boss as we enjoyed our falafel about the department’s work and understanding of gender, roughly translated as “social type” in Arabic. The chasm between us was evident in terms of cultural difference, yet we bonded over small things like the food I had learned to love while living in Jordan.

Settling into the rhythm of the department, my initial observations caught simple things like how people from other departments were always coming in and out greeting my team good morning with a string of Arabic phrases that I would learn to parrot back like Allah yasa3dek (God bless you) or yatik alf afia (may God give you a thousand strengths) that were essential to office etiquette. Instead of shukran (thank you) when I was handed a daily paper cup of turkish coffee I learned to respond islamu idayk (may God bless your hands). More cultural than religious, I understood these interactions as central to office life and began to adopt the practice out of respect for my host environment and colleagues. I learned when I was supposed to say no to 11am tea and when to say yes at 3pm; these gestures represent a small window into the richness of Jordanian hospitality culture.

I would work for three months in the department of gender empowerment, collaborating on diverse projects from training women to report on instances of domestic violence in their community to coordinating and researching for a podcast series on gender empowerment with youths to hand delivering the eleventh draft of a grant application to the Japanese Embassy in Jordan. I learned a lot about NGO work, gender empowerment through a Jordanian lens, and how to navigate Jordan as a non-Arab woman. This forced me to grapple with big questions like:

How do NGOs work and what challenges do they face? How do national NGOs navigate international aid and funding streams compared to international NGOs?

Thinking about my own identity, I asked:

What is the role of Americans and western-educated people generally in “development” work abroad? What does “gender” mean in Jordan compared to in the U.S. and what is the proper way to respect those differences while working in the field of “gender empowerment”?

As a religion major at Barnard, I also wondered how to navigate the religious difference in my perspective as an outsider, working in a predominantly Muslim country as someone who grew up in a predominantly Christian environment with radically different ideas about the relationship between religion and culture/politics. These questions will be addressed in my upcoming blogs, though they have no easy answers. As a white woman interested in international policy and a career either in the humanitarian sector, diplomacy, or at an organization with an emphasis on multilateral collaboration, it was an important summer where I better learned to understand my identity in Jordan and how to be a part of my community. I also ate a lot of falafel sandwiches.

The photo included was taken from the desk cubicle where I usually sat. A picture of the Jordanian princess who served as executive chair of the organization for several decades is seen hanging on the wall.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in