Research: When People See More Women at the Top, They’re Less Concerned About Gender Inequality Elsewhere

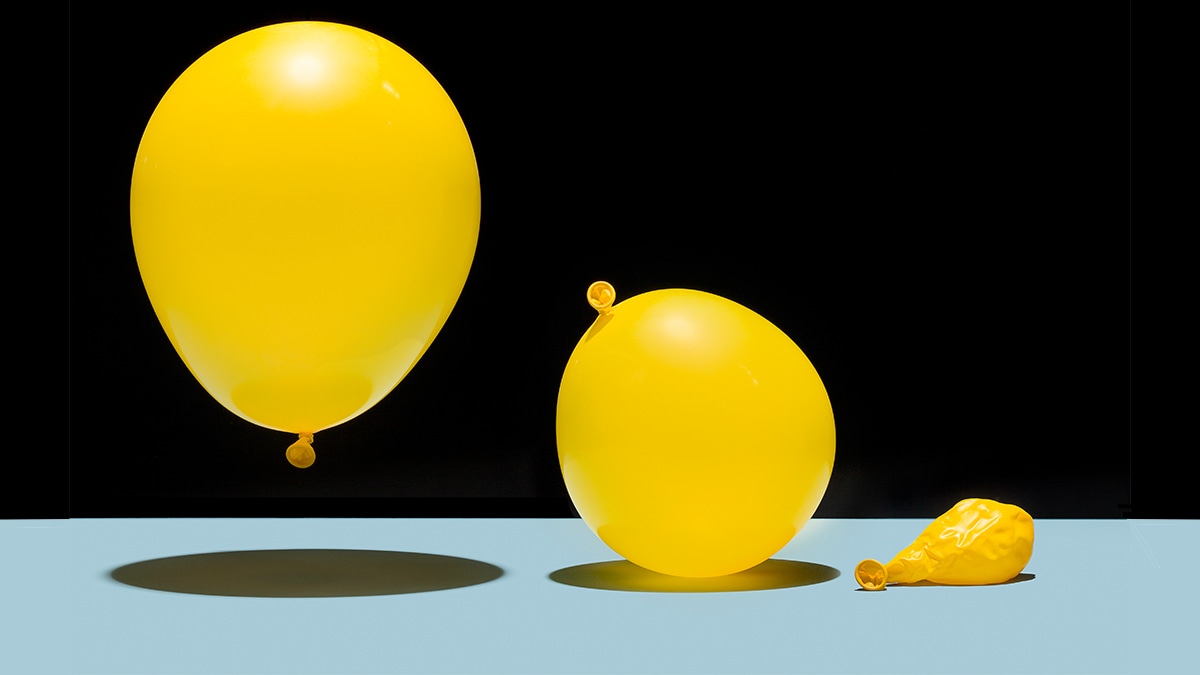

Over the last two decades, organizations have seen substantial progress in increasing women’s representation in top leadership. While the numbers are still far from parity, the general view is that this progress for women in top leadership will naturally spread to improve women’s outcomes in other domains, such as pay equality. But is this true? Researchers conducted five studies measuring or experimentally manipulating people’s perceptions of gender diversity in top leadership, and found a strikingly consistent pattern: when people perceive greater levels of women’s representation in top leadership, they overgeneralize the extent to which women have access to equal opportunities, which then decreases their concern with gender inequality in pay and other domains. These findings are worrisome because people’s concern with inequality ultimately predicts their willingness to address it.

Over the last two decades, organizations have seen substantial progress in increasing women’s representation in top leadership. Consider this: in 1995, there were no women Fortune 500 CEOs and only a few token women on Fortune 500 boards; in 2017, there were 31 women Fortune 500 CEOs corporate boardrooms were 22% women. While the numbers are still far from parity, the general view is that this progress for women in top leadership will naturally spread to improve women’s outcomes in other domains, such as pay equality.

Anecdotal evidence, however, suggests otherwise. Despite women’s progress in top leadership, the gender pay gap in the United States has decreased on average by less than 0.4 cents annually since 1960. Iceland, which holds the world record for women’s representation on boards (44% in 2018), continues to have a 14% gender pay gap — equivalent to that of most Western countries. Gender progress in one domain thus frequently coexists with gender inequality in others.

This led us to wonder: how does progress toward gender equality in one domain, like top leadership, shape people’s concern with persisting inequality in other domains, like pay?

We investigated this question in five studies (in press at the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General), which involved a total of 2,726 U.S. American participants. Across studies, we measured or experimentally manipulated people’s perceptions of gender diversity in top leadership and found a strikingly consistent pattern — when people perceive greater levels of women’s representation in top leadership, they overgeneralize the extent to which women have access to equal opportunities, which then decreases their concern with gender inequality in pay and other domains.

In our first study, we asked 331 employed women and men to read an article about the purported “three most notable business lessons” from the previous year. The article included three columns: one about brainstorming, another on corporate culture, and the last one on gender diversity at the top of U.S. organizations. Only the last column randomly varied across participants — either saying that “women’s representation in top leadership is strong” or “women’s representation in top leadership is low.” We then presented participants with six factual statistics about the gender pay gap, and asked them to indicate their level of disturbance with each of them. To make sure that any effect would be specific to gender-related inequality, we also measured people’s concern with gender-unrelated wealth inequality in the U.S.

Participants who read that gender diversity was strong in top leadership reported less concern with the gender pay gap than participants who read that gender diversity was low. Participants in both groups, however, exhibited equal levels of concern with wealth inequality, which suggests that the effect is specific to gender inequality. Interestingly, this effect was the same across men’s and women’s responses.

Would we see this effect without giving people initial information about female representation in leadership? To test this, we asked 350 employed participants (Study 2a) and a quasi-representative panel of 1,098 Americans (Study 2b) to give us their best estimate, from 0% to 100%, of the current average level of female representation at the top of U.S. organizations.We also measured their concern with the gender pay gap, and the extent to which they believed that women no longer face barriers and have access to equal opportunities.

We found the same results across both studies: The higher participants’ estimate of women’s representation in top leadership, the more they believed that women have access to equal opportunities in society, and the less they felt concerned about enduring gender inequality in pay.

Another study of 454 working participants gave us more insight into the deeper processes at play. We again found that when people learn that gender diversity in top leadership is strong, they then believe more that women have access to equal opportunities in society. We saw that this in turn predicted them attributing the gender pay gap significantly more to women’s personal career choices, which also contributes to explaining why they felt less concern about the gender pay gap.

In our final study, we wanted to test whether this belief that women were well represented in top leadership could also make people care less about gender inequality in other areas, such as in the division of chores at home, lower access to venture capital funding for women entrepreneurs, less pay for women’s sports teams, stereotypical depictions of women on TV and in movies, and gendered pricing (e.g., things like women’s razors and dry cleaning are more expensive than men’s).

To test this, we again randomly assigned 326 working participants to read an article describing gender diversity in top leadership as high or low. We found that participants who read that gender diversity in top leadership is high indeed showed less concern with gender inequality across these different domains than participants who read gender diversity was low.

To sum this all up, we found that seeing progress for women’s representation in top leadership (either spontaneously or after reading an article) leads both women and men to think that women have greater access to equal opportunities. This overgeneralization of progress, in turn, makes people less worried about the persisting inequalities that women face daily, across a variety of domains at work and beyond.

These findings are worrisome because people’s concern with inequality ultimately predicts their willingness to address it. While organizations, countries, and advocates rightfully regard women’s representation in top leadership as an important indicator of progress toward equality, our research suggests this indicator is by no means sufficient to ensure women’s continued advancement in society, as unexpected new barriers to gender progress may ironically arise as women become more visible at the top of organizations. Achievements for diverse representation in top leadership should, of course, be celebrated. For researchers and leaders alike, however, the challenge will be to find ways to publicize progress toward greater gender diversity at the top without jeopardizing progress for gender equality in other aspects of life.

Please sign in

If you are a registered user on Laidlaw Scholars Network, please sign in